Dance is truly the cruelest of the fine arts. Visit a museum and a painting you love, an installation, a sculpture might no longer be on display, but it still exists, out there in the world somewhere, and also online, or in your camera. You can look at it again, and get a taste, a touch, a contact high of what it did to you that first time.

Opera, theater, the symphony—none of them last forever, but some are recorded for posterity, and others exist in other forms. It’s amazing how a show can come back to life even years later simply by reading the script or listening to the cast recording.

Dance is not like that. It happens for a select number of performances in a certain number of venues and is then in all but the rarest cases—Swan Lake, The Nutcracker—no more. And while listening to the music around which a show is built can conjure back up moments or images, they are thin and fleeting, phantoms that vanish as soon as you set to look upon them squarely.

I discovered this for the first time almost twenty years ago.

Each autumn New York City Center invites something like 20 companies from around the world to come and do 20-30 minute selections of their work over the course of a two week, wonderfully inexpensive festival, Fall For Dance. Knowing nothing but curious, I selected a random night, and found myself watching dancers of the KEIGWIN+COMPANY telling playful, romantic, pining stories to the tunes of Rufus Wainwright. It was utterly transfixing, and also transforming. My imagination soared amidst the images that Larry Keigwin and company had conjured the whole way home that night. By the time I got to my room I was desperate to see them again. Probably I told myself I wanted to burn them into my mind, to create a groove that could not be undone, but really I wanted to know I could have them for myself, to possess them now and forever.

But that is not how dance works. It slips away, out of your fingers. I’ve been chasing those glimpses again ever since, going online again and again, looking for some clips and also that unique ephemeral experience of wonder, and finding nothing.

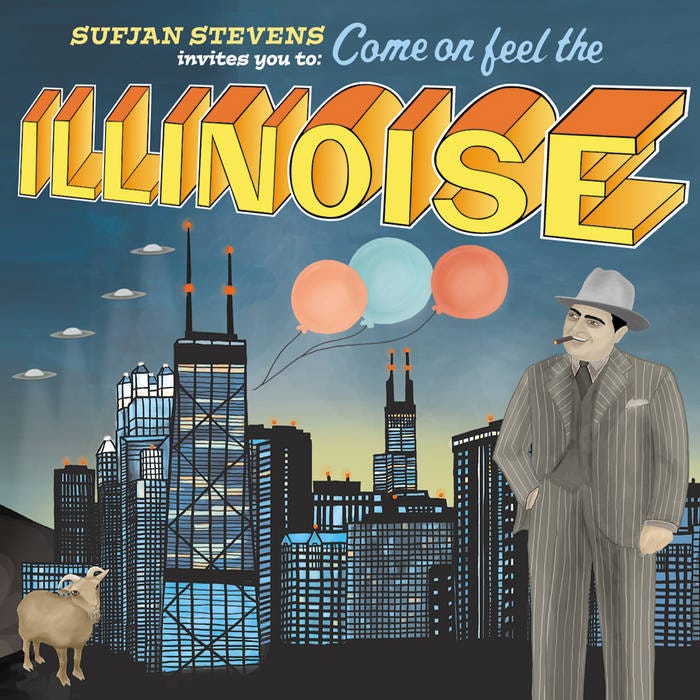

Around the same time that I was having that first, unrepeatable experience with dance, the musician Sufjan Stevens released his concept album Illinoise. It was his fifth album, and his second built around a state, his first being the 2003 album Michigan. At the time he said he hoped to write an album about each state of the union, but later called that a promotional gimmick. While critics praised his songwriting, and it was his greatest success to date, it was a strange, hard-to-get-your-hands-around-it album, with songs about UFO sightings, Superman, and the Chicago suburban serial killer John Wayne Gacy, Jr. Stevens had done immense research about the state of Illinois in writing the book—there really was a UFO sighting in Highland, Illinois, and Superman’s hometown of Metropolis was based on Chicago. But it was hard to say it felt like Illinois, at least not to me, a northwest suburban kid, despite the fact that I spent a lot of my childhood fearing that I would awake in the night to find aliens outside my window waiting to take me or my brother away from our little wood-paneled bedroom which somehow always felt like a boat.

But for me there was one song on the album whose appeal was so undeniable when I heard that it had been turned into a full-length modern dance show, I knew I wanted to see it. The tenth song of the track, “Chicago,” starts and ends with a few mysterious notes played on what sounds like a child’s xylophone, almost immediately bursts into a chaotic combustion of instruments that sound like they don’t belong together and yet somehow drive us forward into the story of two friends on a road trip that is somehow filled all at once with joy, prayer, anticipation, regret, and a Buddhist-like acceptance. “You came to take us,” a chorus sings, sleigh bells playing behind, “all things go, all things go.”

In the show, conceived and choreographed by Justin Peck and playwright Jackie Sibblies Drury, “Chicago” is a central part of the story that main character Henry tells via dance to friends seated around a campfire, many of whom have also shared stories. In some ways the dance is a direct translation of the song—the two of them on a road trip, other cast members providing the lights of their car and others as they ride along first to Chicago, then to New York. But then, as in many of the show’s greatest moments, everyone gets drawn into the dance, and suddenly out of nowhere we’re in the middle of a gorgeous, ecstatic explosion of joy that captures what that trip meant to him, the liberation it brought to his life.

Meanwhile three singers wearing the wings of butterflies hover above with an orchestra, not so much grounding the dance in words as rendering the entire proceedings somehow more mystical, more magic.

Somehow, somehow, somehow—that’s the word that keeps coming to mind as I try to describe what it was like to watch Illinoise, which after its three-week run at Park Avenue Armory is going to transfer to Broadway in April, and has some people already naming it a front runner for the Tony. Somehow the set designers transformed one of New York theater’s weirdest spaces, a massive room half of which is covered in the kind of steel bleachers Midwesterns spend their Friday nights upon in the fall, drinking beer and watching high school football, into what felt like a genuinely outdoor space, all of us gathered around that campfire at which the performers sit telling us their stories. (As the show went on there were moments I simply leaned back to take in the overall setting, to savor that feeling of being a part of an audience outside on a summer night, even though I was inside on the Upper East Side in early March.)

Somehow the performers managed to convey not only every emotion, but every story beat—some of which are far from immediately obvious–without uttering a single word the entire show. And perhaps as a result, somehow, at some point, Peck’s choreography and Stevens and Drury’s storytelling so rewired my brain that the whole world seemed different, the dancers like ancient witches casting a spell, and yet rather than changing reality they had uncovered it and enabled us all to finally see life for what it was, or what it could be.

After the show I walked down quiet streets trying and failing to understand what exactly had happened, when the show had shifted from being not about the story and the characters but about the experience. And I realized I was noticing more of everything—the nearby limo driver’s grey rumbled fedora; the crinkled bell of a delivery man’s bike; the golds and reds and ebonies glowing from within a Central Park South bar. I stepped into the uptown 1 subway station at Columbus Circle to find it strangely empty. And yet rather than eerie somehow—always somehow—it felt like a canvas waiting to be painted upon in sound and movement, in life.

How long will that feeling of new presence continue? Given my past experience of dance, the chase all these years, I fear the answer. But maybe this time is different, maybe it doesn’t matter exactly if in my mind that 2-hour experience on a Monday night in March is reduced to ghostly tatters mostly out of reach. (Although so many moments—“Jacksonville,” “Come On! Feel the Illinoise,” “The Tallest Man, The Broadest Shoulders,” “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.”—remain still so present in my mind.)

Because Illinoise showed me that the thing to be chasing isn’t the show, as though it was some kind of magical creature I could capture and keep forever like the lightning bugs that descended upon our neighborhood each summer of my childhood (and which also open the show), transforming the darkness, but that fuller vision of the world which it gave me. That world is all around me even right now a week later in this Upper West Side coffee shop, where a woman in a crumpled mustard stocking hat pours her attention into her phone, her coffee cup held like an afterthought in her other hand, while a mother nearby rocks a baby carriage covered in a rose blanket, the tiny pink and purple and seashell sweater of the unseen child hanging from the handle, and the hiss of a liquid being boiled rises and falls, and in a slate grey carrying case beside me, two dogs sleep, the breathing of the black and white one slow in and then fast out, like a heartbeat.

I remember studying theology a conversation we had about the notion of eternity. How can we, as time-bound creatures, even conceptualize of what something outside of time might look like? Our professor suggested as outside of the constraints of time, perhaps eternity is something that is always present in everything. When religious figures like Jesus speak of the inbreaking of a spiritual reality like the Kingdom of God, perhaps that’s what they’re talking about, a glimpse of that bigger, fuller picture emerging. Perhaps when holy books talk of scales falling from people’s eyes, that’s what they see.

“You came to take us, all things go, all things go,” Stevens sings again at the end of “Chicago,” but not just that: “to recreate us, all things grow, all things grow.”

This was wonderful...love the imagery.