THEATER WOW: I CAN GET IT FOR YOU WHOLESALE'S MARK WENDLAND

On Keeping Things Simple and Yet Still True, and the Power of Collaboration

I Can Get it For You Wholesale tells the story of a working class Jewish shipping clerk working in the New York City garment district in the 1930s who dreams of becoming a rich man and has to decide how far he’ll go to get there. It was the show that gave Barbra Streisand her first break at age 19, and her first Tony.

Classic Stage Company, which is currently doing a very well-regarded revival of the show, performs in a relatively small space where the seats begin at the same level as the thrust level stage. It seems like it would be a challenging space within which to do set design, and yet scenic designer Mark Wendland did a masterful job, using the back wall to create a skyline of New York out of the materials used in the fashion industry, and rolling desks and wooden chairs that could be moved constantly to represent the change in scenes (and mood).

Wendland has done scenic design on dozens of off-Broadway and Broadway shows. In fact, his designs can be found right now on Lincoln Center’s Gardens of Anuncia as well (and they are equally gorgeous). He was kind enough to talk to me as he was just beginning his Thanksgiving cooking. I posted a tease of our conversation over the holidays. The full conversation follows. Content has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Had you worked at Classic Stage before? To me it seems like a daunting space to do scenic design.

Back in the late 90s, David Esbjornson was the artistic director [at CSC], and he hired Brian Kulick to direct a production of the French play Amphitryon. That was my first time.

By a weird fluke of chance, Brian became the artistic director at CSC for several years. When Brian was there, I think all in all I probably designed 6 shows in the space. So I know the space really well.

I thought what you did with …Wholesale was so lovely and creative. I was really blown away.

The stage of …Wholesale at intermission. Note the rolling tables at the back, and behind it the New York skyline constructed out of materials used in the garment industry.

Well thank you for that. It’s funny, I think ever since CSC was a theater, the seating orientation was like a 90-degree pivot, so the back wall was not under that gallery. There was audience under there and the back wall was actually one of the long wide brick walls.

I always hated that configuration, I thought it was so stupid. I said to Brian every show I worked there, Hey do we have the money, could we just for the show rotate the seating? *laughs*

John Doyle changed it when he took over, but I had never worked there when John was there. Coming back I was like, Oh this is my dream come true! It happened!

It’s long and narrow, but somehow it seems like it fits in the space better. So no, I wasn’t daunted at all.

For this show, how did the design for the stage come about?

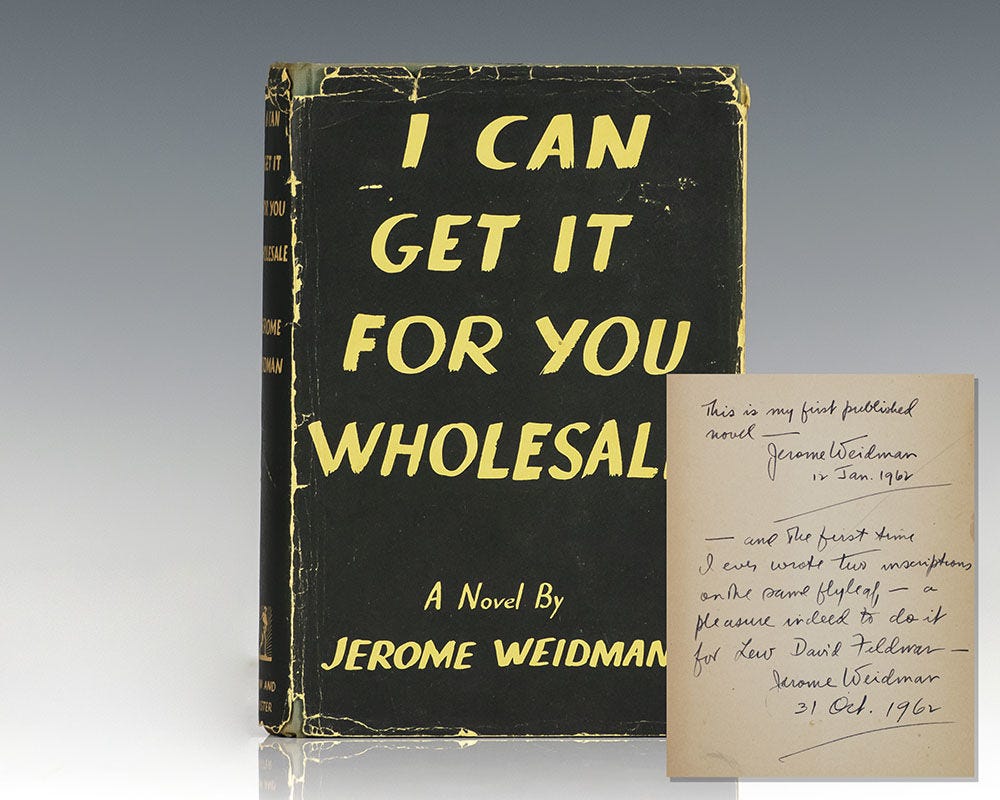

You know, the book was completely rewritten by John Weidman. It was his father who wrote the original book for the musical, back in the ‘60s, based on a book he wrote in 1937. In 1937 it was kind of well-known because it was one of the first times that a work of American fiction was written by a Jewish author, sort of confronting the story of the Jewish immigrant experience in America.

The reason it garnered a lot of attention in 1937 was that the original novel took a sort of harsh look at how the Jews of Eastern Europe were sort of forced into this place of assimilation to survive in America. The musical alludes to how the garment business was one of the few businesses that Jews were even allowed to rise in. There was other work you could do, but no job actually allowed you to thrive. And it really took a hard look at that dog-eat-dog world.

But when John’s father Jerome wrote it as a musical in the ‘60s, he kind of softened out all of the harsh social critique of the novel in order to satisfy what was expected of a musical in 1960. So what John and the director Trip Cullman wanted to do was go back to the novel as source material and really excavate that social critique, which unfortunately is still very pertinent today. The novel in many ways was a critique of capitalism, and I think they wanted to put that back in the show.

One of the ins of reworking the musical for Trip and John was using that very lush orchestral overture as an opportunity to do some world building. In the original music the overture was just an overture. It was John and Trip’s idea to physicalize it and kind of show the world that Harry Bogen was raised in and sort of how he became who he became. The idea of showing him as a child working for pennies carting fabric around to all the different vendors in the garment industry was one of the key storytelling tricks that Trip was really eager to do.

I think that was the seed that planted the idea that we need to visually inhabit the streets of the garment district, with all its bustle. And of course the prologue ends with the money that young Harry’s worked so hard all day for being stolen and then him being called a racist slur and going home with his tail between his legs. That whole sequence was not in the musical, and we felt the onus to figure out how to visually tell that story. That was I think the genesis of having all of the detritus that would go into a New York City sweatshop on stage somehow. Out of that, the rest of the design kind of grew.

That back set is one of my very favorite things, the skyline that you create out of dress-making equipment. It’s beautiful. And I love that it also has this amazing layer that the apparent glamour of New York is actually built out of the dehumanizing brutality of the sweatshops.

I don’t think Trip or I were really talking about it to each other in that way in the moment. I’m not a native New Yorker; I was born in Los Angeles. And I remember the first time I came to New York as an undergrad for a long weekend. You land in Newark and take the shuttle and you see the skyline of Manhattan and it is like a dream. For everybody, it’s like “Oh my God, Manhattan.” It’s a dream world, it’s a land of aspiration and goals and pulling yourself up by your bootstraps and If you can make it here you can make it anywhere and all of that. I think we had all of that in our heads as Harry’s dream.

The thing I realized later is that visually we were fabricating that sort of fairy world, that dream world, out of the junk that goes into making a dress. Eventually I realized, Oh this is very cool, because it has this extra layer of meaning. I didn’t see all those layers originally, I was just thinking Harry is trying to make his dream come true, and we’re showing how everybody else on stage, everybody else working in the garment district are little cogs in the machine of trying to make a buck by selling a dress.

It fascinates me how you didn’t even realize that second layer of meaning was there. Do you find that happens a lot as an artist?

I think all creative people have that thing of sitting down and actively trying to go to work on the thing that you’re trying to create. But what always happens, I think this is universal, is that the real work of creativity happens in that moment where you create a meditative state.

When I was first starting out, I always had my best ideas in the shower, because you’re just zoning out and doing something mechanical that you don’t have to think about. And then suddenly you’re like, Oh, I know the answer!

I think a lot of my best thinking now happens when I’m asleep. I just need to be in a place that’s calm enough during the day to remember that unconscious thought that I had in a dream. Yeah, that happens all the time. I think that’s just the way our brains are wired.

The rolling desks are such a great device. Practically, they let you change scenes so fast. But they also seem to allow the cast members moving them to convey the energy of the moment, especially as things get worse. How did they come about?

I don’t quite remember. When I first got offered the job, I went online and did a bunch of research of garment factories and sweatshops from the period from all over the world. There actually is a lot of amazing photographic representation of the garment industry. It’s sort of shocking how much these workers’ lives were captured on film.

And when you see the pictures you understand why they call them sweatshops: all the men are in their button-down Henleys. That was a time when you would never take your shirt off in front of a woman. But it just looks horrifying. It was obviously very very horrible working conditions, and everybody’s hunched over a table into which a sewing machine was built. In the research they went on for miles, and we basically took that vocabulary of these sewing machines pushed face to face to face as inspiration.

I went through with Trip and storyboarded some ideas about how we couldmove from scene to scene to scene just with tables and chairs. There are two scenes that are written in the text to be the character Ruthie’s stoop in Queens. But what are we going to do at CSC? We’re not going to bring in a flat that looks like the front of a brownstone or whatever.

So it was finding a neutral vocabulary that was in suite with the detritus of a sweatshop, but then also could be flexible enough to be all the other locations that we go to.

Would you say you were aware of the set from the start as providing the cast a way to express the emotions of their characters?

Most of the shows I do with Trip, I work up a little sketch for each scene. But the way I approach the sketches is not about showing the set, it’s indicating how can the scene be staged. In other words, what do the performers need to do physically in order to tell the story?

And I think this is just my taste, but I think how little on stage can we get away with? Basically, it’s performer-forward, it’s not spectacle-forward. And definitely at CSC it has to be performer-forward, just because of what the space is giving you.

So our first priority was to figure out, What does the cast need? And then the second thing was, How do these tables and chairs facilitate that need?

Trip and I spent 2 or 3 days in these 4-hour shifts where we would play around with rehearsal tables and folding chairs just to kind of feel out in real space, in real scale how does this feel in the room, is this going to work.

It was only later [with the actors] that we were figuring out how to make getting from scene to scene to scene not feel cumbersome. And there were definitely days when we would have a shift going from one look to another that was drastically different, and we’d be like Oh my god how is this going to work, this is never going to work. And the cast was like, freaked out. “Why are there so many chairs? I don’t understand.”

But that’s choreography. Once you kind of get it into your bones [and] once the audience gets there, they don’t know. It sort of seems magical if you go from one look to a look that’s completely different.

There definitely were days where I thought, Oh shit what have I done? I’m killing the show. But I think the cast ended up doing an amazing job of making it seem like choreography. It seems very effortless. They’re amazing.

That sense of magic seems so apt to the show. There are shows you go to where you’re so aware of the scene changes, and it can become a problem. Whereas in …Wholesale, it’s so seamless you don’t even really notice it. The only thing you’re aware of is the emotions that the actors bring to the moves, which really feed into the scene that follows.

To be perfectly perfectly honest, the cast of …Wholesale is a dream cast. Many of the performers I’ve worked with before, and Trip has worked with before. And without naming names, the two that I’ve worked with the most are truly two of the most open-hearted collaborative people who really are there to serve the event. All of them are, really.

And one of them was like Mark, Why are there so many chairs, why do we have to have so many chairs? They’re just getting in the way!

And I was like, I have to tell you, the reason you feel that they’re in the way is because you’re so in character. Your character is frustrated. In Act 2, when there are chairs littered everywhere, you’re having to move them around, you’re having to turn left and then turn right and then turn left and then move one out of your way. That’s giving your character all of this physical tension.

And he was like, Oh, that’s interesting. I’m feeling tense, because all of this shit’s in my way. And I was like Yeah, to me that’s cool because the audience is feeling that physicality. Whereas if there were half the chairs, it would be this big open space and you could move any way you want, and that wouldn’t be serving the tension.

Act 2 is such a motor of the horror of watching this man constantly be making the wrong choice. For the choice to make money he’s turning his back on his family and his community. And for me the clutter of the tables and chairs helped that.

This is a long-winded way of me praising the cast, because they were always like, Okay, let’s try to do it this way. They always used what was there in the space as a opposed to not embracing it. And I think for some of them that was a leap, and I love them so much because they found a way to make it serve their needs. That’s a huge skill. A huge kudos to all of them.

What would you say was the biggest challenge in making the design come to life? Were there perhaps things you considered doing but didn’t do?

The reality of off-Broadway is to try and come up with an idea that’s achievable within the budget, but also just within what the team that the theater has could be able to achieve. CSC doesn’t have a full-time technical director, they don’t have a scene shop. So you want to come up with something simple.

But at the same time, the idea for this design required all that stuff upstage to kind of looking real. Because if it looked fakey, the event would not be as honest-feeling. We were trying to do something that had a lot of truth and honesty.

So I think one of the biggest challenges was just having the time and money to make sure that everything that was physically represented through the scenery and the props had as much of the specificity of the time and place that the story was being told in.

That wasn’t just a challenge for me. I think of Ann Hould-Ward who designed the costumes and her associate Isabel Martin. Every day I would come in, usually early, and they were always there before me, and they were always the last to leave. Doing a period show with such a big cast in a venue like that is such a huge challenge for costumes.

I think that was the greatest challenge, working as hard as we could to conjure the world of 1937 New York, and have the visual experience feel like you’re being transported to another time, and doing that within the physical reality of what off-Broadway is.

It’s interesting to think about that idea of being transported in this space. You’re so close to the performance, I wonder if that doesn’t add to the challenge: The seating doesn’t separate us or create that sense of a separate, magical space in front of us. The visuals of the set and costumes seems like they end up having to do more.

One of the things Trip and I and the whole creative team talked about a lot is the WPA and that special conch of money during the Depression directed to the arts, and specifically to live performance. Because it was on this very limited government dole, those productions were famous for being done almost as story theater. The emphasis was put on the performer and the text, and the visuals on purpose by design were very low tech—because they had to be, but that was the style. And it ended up creating this style of theater like agit prop theater, which was very much in our heads.

So we were trying to follow that period-specific model. We’re a band of theater makers telling you this story about the 1 percent and the 99 percent by the seat of our pants. And it seemed like the seat of our pants aesthetic served the political agenda. When you get to that 11 o’clock number, “What are They Doing to Us?”, which is sort of the cris de corps, for me it’s sort of the reason to do this play right now. And I think the aesthetic of the event was trying to be honest to the sentiment of the words in that song.

Whereas if there was more eye candy, it would be like a sweetener to leaven the event. And I think we were anxious that the event didn’t have any leavening, that it didn’t have any extra sweeteners.

The structure of the show is very interesting, because in Act One it gives you all of these beautiful, sort of traditional Golden Age of the American Musical love songs and ballads, and sort of upbeat comic numbers. But it really boils down to this man who sells his soul for money.

And so I think if there had been more beautifiers in the event, it would have been sort of lying to where the play actually leads you. I think it would have been a visual misdirection in a way.

One last broader question. What’s the aspect of scenic design that you’d say rarely gets talked about but is most important or meaningful to you?

You know, I teach now. I started teaching about six years ago. I’m the head of the design and production program at Fordham University. Because of that I come into contact with directors and playwrights, and obviously designers and stage managers. A lot of them take my classes. It’s an undergraduate program for undergraduates in theater specifically.

I think in the theater the biggest thing is there’s a tendency, there’s a real thing in all the arts, to silo artists. You’re country Western, you’re alt-pop, you’re folk music, you’re grunge. Every artist needs a label.

But that’s stupid. People aren’t labels. People have many many many sides. And I think when I look at the scene designers whose work I respect the most, they’re the artists who don’t come into the process being like, Here’s what the set will be! It’s more about the collaboration that goes on with the entire team about what do we want. Why are we din this play now? Why is that story important? And how do we as the entire artistic team communicate that?

That’s very difficult for undergraduates to hear. Because if they go to school to be a lighting designer, they don’t want to talk about the set, they want to talk about “Oh, I think this scene should have green gel.” And it’s like No, that comes later. Talk to your whole team about what the event is, and if you know what the event is, the gel will pick itself.

So I think for non-theater people, a good thing to realize about the craft of theater making is that the people who are doing it, the people who are working in the industry in a wholistic way are the people who are making the best art. Because it really is coming from the hive mind. People will say Oh, your design. And I’m always like, That’s not my design, it’s our design. We all made it together.

I’ve worked with a lot of directors who, that’s not their jam. They want it to be like the show rises like Athena from the head of Zeus. But that’s just not honest. That’s sort of self-aggrandizing. I love Trip so much, I’m a huge fan, I’m always desperate to work with him, because I think he’s just genuinely discovered in his life and his career that the best work comes out of reaching out to all of the talent in the room, and letting all the talent in the room contribute all that they can. That doesn’t scare him. He invites that.

Thanks to Mark Wendland for this conversation. I Can Get It For You Wholesale is playing until December 17th at Classic Stage Company. Marks’s other show, The Gardens of Anuncia, is playing at Lincoln Center through New Year’s Eve.

In the weeks to come, stay tuned for more conversations like this for subscribers, including one with my favorite performer in Chicago. And see you Monday for the Wow!