SPIRIT WOW: BILL GLENN!

On tenderizing hearts, overcoming shame, and how a gay Franciscan who called everyone "Girl" helped set him free.

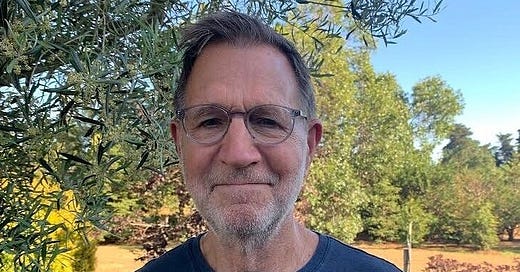

Last weekend I teased this conversation with Dr. Bill Glenn, a psychologist, theologian, writer and all around good guy from Northern California. The thing about Bill is, after you’re done talking to him you realize you have so many new ideas to think about. Sometimes it’s the things he says—like his comments about the Catholic idea of “salvation” or his image of queer people tenderizing hearts. Sometimes the ideas just come as he’s talking. It’s like his presence opens doors for you to walk through. I hope that’s true for you, too.

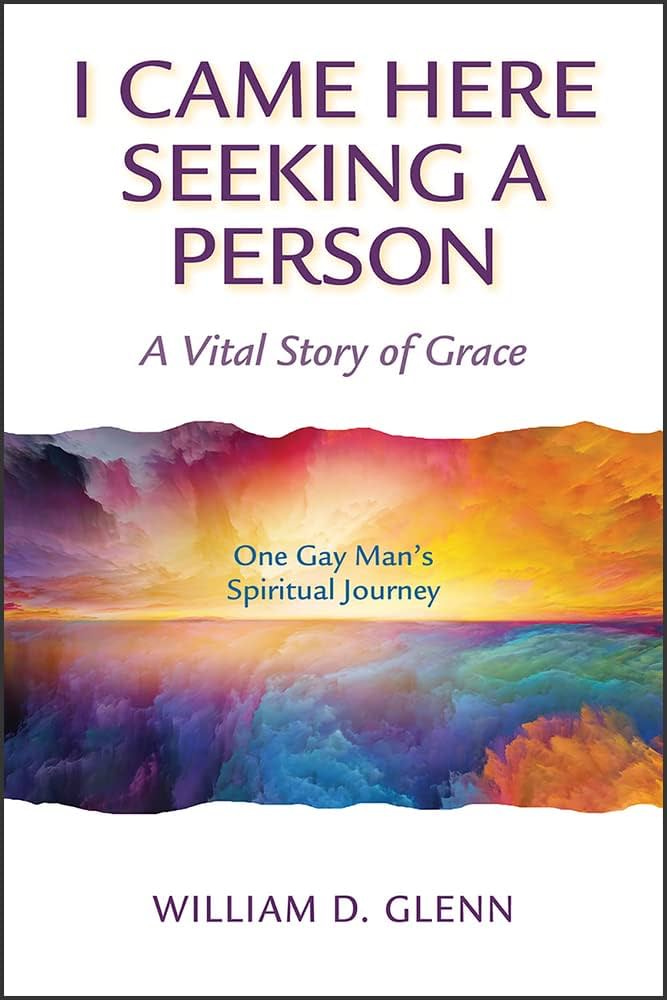

Bill and actually met as a result of this newsletter. He saw something I had written about being on leave from the priesthood, and reached out to introduce himself. Bill is a former Jesuit himself, and of the Wisconsin Province, which is the province I’m from too. And about a year ago he published a book called I Came Here Seeking a Person, which is about his journey in and out of the Society during the height of the AIDS pandemic, and the way that God has continued to move within himself since all that.

One of the things we don’t talk about much in our conversation is Bill’s many decades of walking with people with HIV and AIDS. It’s a bit of a glaring omission on my part, honestly, and less surprising than I would wish. In recent years I’ve started to realize that my own lack of self-awareness about my sexuality until my 20s was probably in part a function of a deep fear of AIDS. And I think that’s something that I continue to wrestle with. Blind spots are so often the shadows cast by our fears, aren’t they?

So on this World AIDS Day, let me just begin with this quote from Bill’s book.

My years of working in the epidemic taught me this: We are given each other, but only if we are willing to break out of the alluring prisons that keep us apart. The most complicated and simple truth is that we are made for love. But to receive this terrible knowledge, we are required to let go of the lie that keeps us wedded to some false and puny facsimile of our divinely wrought selves, to be vulnerable enough to avail ourselves of this vivifying love, the only force that transcends every other force we know.

Onto the interview!

Tell me about the title of the book, I Came Here Seeking a Person.

It’s a quote from Thomas Merton. It’s a quote from his book Notes from the Gestapo. I come into this life seeking me, who is this person that I am; seeking you, who are you that have entered my life; and the divine person.

Seeking is the right word for me. I have been seeking myself since I was a very young boy, I always have been seeking the other, and I’ve always been seeking the divine. I’m still seeking that ineffable mystery.

I love Merton deeply, he and Teilhard [de Chardin] and Jung have been my three major life companions. Merton in particular, he was the most human of beings. I’ve spent the last 60 years reading Merton. He was attuned to everything from that little cell in Gethsemane.

I think the “here” is what grabbed me. It could mean so many things.

I came here into this Glenn family, I came here into the Society of Jesus, I came here into a world of sobriety, I came into the world of AIDS, I came into the world of psychotherapy….I came to all these places to do this exploring.

I was always a gay person but I had to come here to be gay, meaning come into my sense of my sexuality, which is way more than my sexuality. My soul is tender-ized by being a homosexual in the world.

I had to come to that. I resisted it mightily for 15 years, I mean mightily.

When you look back on the resistance, what do you think you were afraid of?

I was afraid of the judgment of God, as interpreted by the Catholic Church in which I was raised. The mental community judged me sick and the legal community judged me an outlaw and the social community judged me aberrant and unworthy. And I incorporated all of that. I was so afraid.

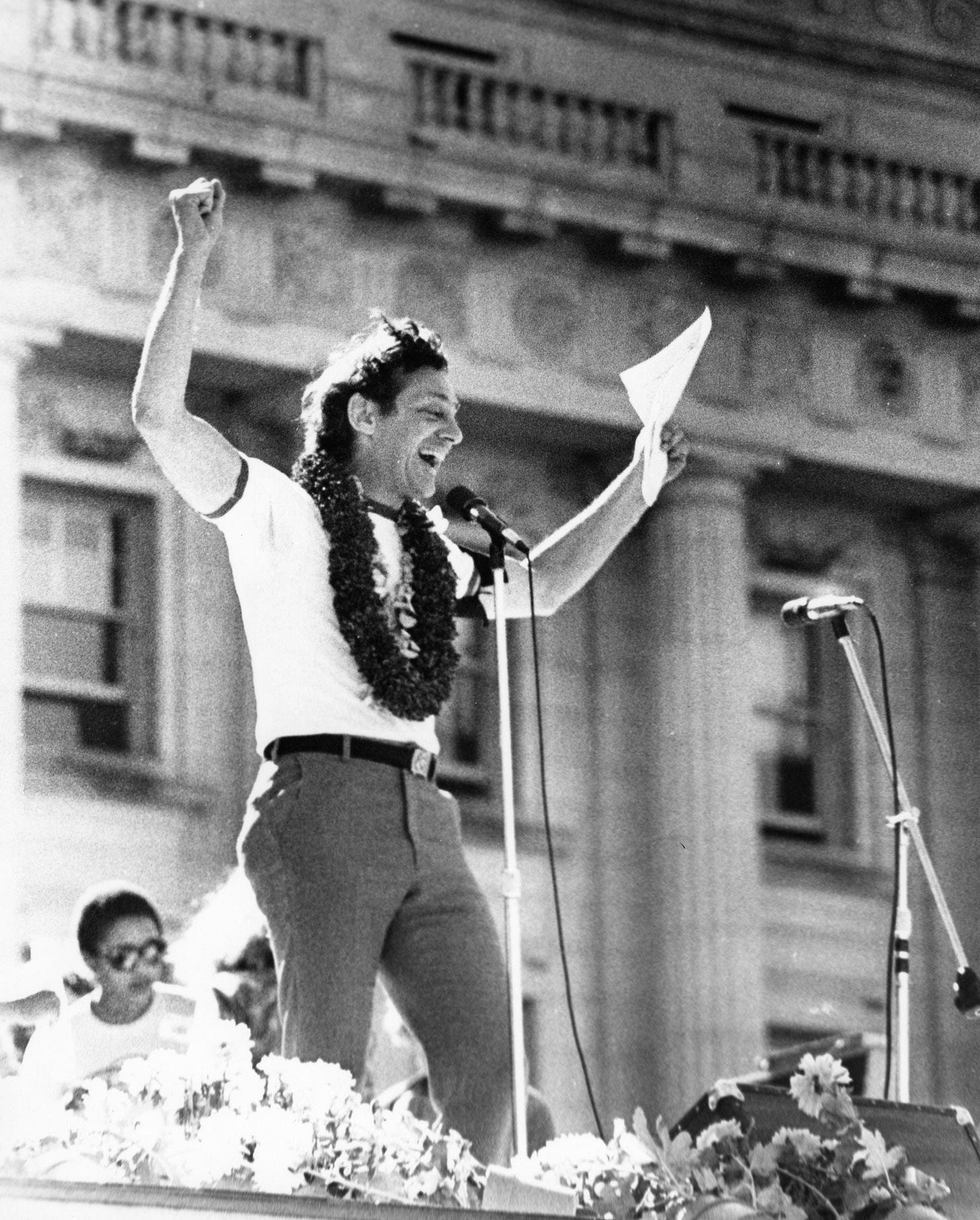

I never imagined I would come out of the closet. I never imagined I would be able to get myself out of this morass. And I was lifted out in one moment by Harvey Milk. He was the vehicle the divine used to tell me, You are a human being, brother, and you get to be yourself.

You tell this story in your book.

Yes. Milk was giving this talk at a campaign rally about this heinous proposition on the ballot that would have required all gay teachers to have been fired summarily. Catholic, public, all. And at this rally in late October, 1978, he got on the dais and he said, “We’re here because we’re not afraid, we’re here for the little boy in Bakersfield, for the little girl in Fresno who believe they’re all alone and they’re suffering the shame we know about, and we’re here to liberate them.”

And I’m thinking, Who’s ‘we?’ I’m not ‘we.’ I’m the little boy in Bakersfield. I’m the one who thinks he’s a piece of shit. He broke through that. I pulled the tab out of my Roman collar and I started to weep. I was both exhilarated and ashamed at what I had done to myself and others. And I went home to my Jesuit community in West Oakland and I wrote out “I am a gay man.” I knew that for forever, but those words, I could not say them.

My life has been dotted with very significant moments like that. And I’ve learned to pay attention to them. When they come, they come with a force. And you avoid them at potentially great harm to yourself.

That idea of queerness as a “tender-izing” force in the world, I find it really powerful.

I believe one of the reasons we gay men are on the planet is to tenderize straight men, in addition to tenderizing each other. So: You are a gay man, and you have done some hard work to get there, and you’ve tenderized yourself in the process. You are open and you treat yourself with dignity and respect, and you give yourself permission to have your full life.

But in this culture straight men are in a jacket that is as confounding and prohibitive as gay men have been. And in their encounter with gay men, not all but many, that they too get to have open hearts, and access to all of their feelings.

When you were here you made a similar comment about the Catholic Church, that the presence of queer people in the church is this essential engine of conversion, tenderizing the hearts of our fellow Catholics.

My affiliation with the Roman church is pretty thin, but I think queer men who stay in it, their presence in the church calls particularly closeted gay men but all to open their hearts to a deeper reality than they have known. I believe every Jesuit I ever encountered, with the exception of some real dolts, knows the deeper truths that you and I have acquired, but many of them live in profound fear. What’s the fear of? It’s a fear of a lot of things: that their intuition is wrong; that they’ll be shut out; that they’ll be kicked out; that their families will disown them; what will they do with their lives. All of that. And you pay the price for that.

In the first lines of John’s Gospel in the Jerusalem Bible, which I love deeply, Jesus is walking down the shore and he sees Peter and John over there. And the Jerusalem Bible’s translation is, “What do you want?”

What do you want? All I ever wanted since I was a boy was to be myself. That’s enough. I can do anything else, once I’m willing to be myself.

I have great friends both in and out of the Society. But when I came out of the closet, the way my provincial spoke to me... I told him I was gay, which was me saying, I am finally a human being, which is all Ignatius wanted, men who were themselves to be men for others, because you can’t be a man for others if you’re not yourself.

And he treated me with this disdain. And I knew the handwriting was on the wall. To live with the clarity that I had, and the passion I had to help free people by living my life, I knew that could not happen in the Society.

There’s that story you tell earlier, too, about being in theology studies with another guy who you grew really close to, and how one morning you went to his room and every trace of him was just gone.

We were clearly in love with each other, though we didn’t use that language. The moment we met, we were drawn to each other powerfully.

It was so symbolic that his room was empty of everything. It felt like the judgment of the church slamming down on us. The most physical we ever got was holding each other.

And you had no idea what happened, whether he had chosen to leave, had been kicked out or moved. He was just no longer there.

There was no explanation, from anyone, ever. Ever. Nothing was ever said.

I realize in that era Jesuits sometimes did just leave like that in the dead of night, but that still sounds completely insane.

I blamed the rector, who was a total asshole, and from the same province. He had all of these gay scholastics, and I think he found it intolerable.

When I want to sign my papers to leave 8 months later, the superior could not look me in the eye. He couldn’t say a word to me. I signed my papers in silence. He said it’s over there, and there’s a pen, and that was it. I was like, wow, this is the summation of my 9 ½ years.

My heart was formed as a Jesuit. And I’d say to you, I’m still a Jesuit. But Matteo Ricci was my model, or Xavier. They went on a mission, the Gospel mission, and they didn’t come back. Matteo Ricci figured out how to dress like a Mandarin, and I figured out how to really minister to the gay community during the AIDS epidemic and subsequently as a therapist. I couldn’t have done this work otherwise. And no one was doing this work.

I also believe that if all the Jesuits who are closeted gay men came out of the closet, the church would have a reckoning of astounding proportions. Astounding proportions. It would change the church and it would change the lives of gay people in and out of the church.

I often think the same. I very much appreciate both the fears and obstacles that stand in the way of queer priests, nuns and brothers from coming out, but I often wonder whether the church will ever truly embrace queer people until they do.

It would revolutionize it. I’ve known many gay priests. And they are waiting for the Vatican to say it’s okay. And the Vatican is never going to do that. Change doesn’t happen from the top, it happens from the bottom.

One of the other things I love about the book is the mentors you encounter along the way.

[Fr.] Peter Fleming and [Dr.] Mario DePaoli, I would not be here as I am without those men companioning me and telling me some blunt truths about my life.

Peter had been a scholastic at [Creighton] Prep when I went there in 1962. He was kind of a gruff guy, big, a commanding personality. He knew how to use his weight. But I had an intuition in theology studies that he should be my spiritual director.

So I went to him. And he treated me in the way I suspect, if I could personalize the divine, the divine would treat me.

Meaning what?

I couldn’t look at him. And he came over to my chair and lifted my chin up. It was such a gesture. And he said, “You have a right to be here and you have a right to approach all of your problems with dignity.” That was the most unheard of thing. “Dignity?” Are you kidding? I’m a homosexual!

And he attended to me for two years. And he protected me from the community superior. And he required that I claim my full self.

Mario was like the psychiatric version of Peter. Mario, the first time I went to him, I wrote about this, I couldn’t look at him either. And I said, well I’m here because I think I’m a homosexual. And he said, Do you mean you’re gay? And I said, Yeah I’m gay.

I couldn’t look at him the whole session, and I come back the next week, and this is how he begins the session: “I don’t want you to use that word in this room anymore.” And I said, what word? And he said, ”Gay.”

Why not? And he goes, “Because you use it like you’re bludgeoning yourself, and I’m not going to have blood on my sofa.”

I looked at him and I knew in that moment, Oh this guy is totally onto me.

And there is Larry Tozzeo, the HIV-positive Franciscan and school teacher, who you talk about helping you to loosen up after you had left.

He was just this free spirit. He did exactly what he wanted, he loved the poor, he served people beautifully. And he used the word “girl” like it was the only first name any human being had ever been given. “Girl!” He shocked me into letting go. He had enormous impact on me.

You tell this incredible story in the book of him asking you to hear his confession when he was dying, and then giving you his stole to keep after you did.

I struggled for years, because I was asked to do sacramental things all the time by people who knew I had been a Jesuit, or intuitively knew I had been formed in ministry. And I would tell them I don’t have the authority to do that, I’m not authorized, I’m not a priest, I’m just a guy like you. And they’d go, Well you are and you’re not.

When Larry did that, it was the beginning my having to accept my priesthood “outside the walls” of the church. People are hungry and they want to be fed. All of those men who came to my talks, most of them are gay, but not all, and they’re wounded. The church has yet to decide to embrace them fully as they are and to allow their wounds to be opened and cleansed and sewn up, which is all Jesus did walking around Galilee. He just opened wounds, cleaned them and sewed them up, and they called that healing. And it was. That’s all the church really needs to be doing on planet Earth.

Those men still desire healing from their self-loathing because it’s hard-wired, it remains in our psyches and we are triggered by it. All of us.

As I read that section about being in a sense called to the priesthood by Larry and others, I thought, Wow Bill has such a different experience of authority in the church, where it comes from and how it’s properly granted.

*laughing*

But as we’re talking now I’m thinking to myself, does Bill even care about authority in the church? Is that even a useful category for him?

When I was a Jesuit and for some time after, authority was the god that I worshiped in the church. I was a pretty straight arrow. I mean, I had my political opinions and my social justice opinions, but I didn’t challenge anybody, I didn’t ask for anything. I just did what I was told.

I don’t want to offend you by saying this, but now the authority of the church has no valence for me at all. That doesn’t mean I ‘m not respectful of much that goes in the Roman church. I am. When I’ve worshiped at St. Francis Xavier, I really appreciate being there.

And I go to Catholic mass whenever we’re abroad, because I can’t understand the priest *laughs*, or the canon [the Eucharistic prayer]—the canon is meaningless to me the way it’s droned out. I love the eucharist deeply, and that’s why I’m involved with the episcopal church, because it’s a eucharistic church with profound awareness of what is transpiring as the bread and wine become the body and blood of Jesus, and that is vital to my life.

Bill and his partner Scott Hafner.

How is that church different for you?

Partially it’s different because everyone is there by free choice. No one has to be there, no one has any sense of obligation to be there. So the community is there because they want something. There’s no remnant of Have-To.

And because they’ve done a lot of work in the last 50 years, there’s nothing in the polity of the Episcopal Church now that says to anyone, We accept you, but you’re not full members. Everyone is welcome in every ministry and at all tables. That’s very freeing. I didn’t know how freeing until I experienced it.

I talked at Mass last Sunday and I’m preaching at the first Sunday of Advent, and it’s total freedom for me. Because I feel the man I am is who they are inviting to minister, not a version of the man I am or the closeted version or the version that’s also required to uphold dogmatic truths that I don’t believe in. There’s very little dogma that interests me. I think a lot of dogma was devised as a way of maintaining the patriarchy.

The term “salvation” is not meaningful to me. Grace is very meaningful, the person of Jesus is meaningful, divine presence in the world is meaningful. Love is so meaningful.

What is it about the term salvation that you don’t like?

It suggests that the creator created a flawed entity and it’s his responsibility to rectify the flawed entity by hanging Jesus on the cross. Jesus was the “expiation factor;” he had to take had to put the second person of the Trinity on the tree ignominiously to rectify his flawed creation.

That is not the way I understand things. I believe there’s terrible evil in the world and I’m part of it. But I don’t need to be saved from that evil, I need to transform the evil within me through the grace of God, through the person of Jesus. It’s not Jesus is coming down to save me. Jesus came to teach me how to be a human being and to live my life with integrity, honor, truth, courage, love.

That isn’t what salvation means in the dogmatic churches. It’s a really fucked theology, in my view. I don’t know if you know Roger Haight, but his book Symbol of God changed me. That book is so magnificent. And what he and others are doing, like Jon Sobrino, they are recrafting Christianity to make it available to people with a modern sensibility.

Teilhard did this, he knew deeply the presence of the Cosmic Christ, which is the most appealing image to me. The Cosmic Christ, meaning that the universe is totally flecked with the divine, and our work is to let it filter into us.

So yeah, I don’t use salvation.

You talk in the book about being in an environment where there is no cross on the wall, and what a change that was. I remember when I started school at UCLA noticing the same, and how liberating it somehow was.

The cross is not unmeaningful for me. I’m in my study right now and I have a cross I bought from a Mexican shop in San Francisco. It was probably made in the 19th century, it’s falling apart, Jesus doesn’t have feet, and I love it.

But in that moment I was aware, I’m in the secular world now. There’s not some protection on the wall for my work. I have to supply the cross in this office. And we do that by inviting people to embrace their suffering, embrace their faith and work it through.

Thank you, Bill Glenn! Everybody, get out there and buy his book. It’s so good! A perfect Christmas gift.

More interviews like this to come! And I’ll be back on Monday morning with the Wow.

Great interview. Thanks for making all these ideas available to us, Jim.

You bet! It's my pleasure.