QUEER WOW: SYDNEY'S QTOPIA

In Sydney, a must-visit new museum explores the struggle and celebrates the life of the Australian queer community.

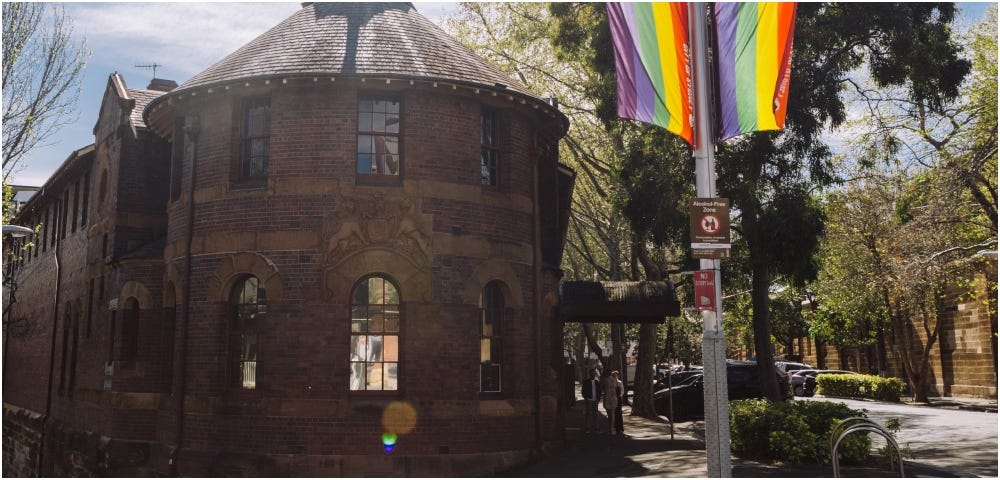

A year ago in the Darlinghurst neighborhood of Sydney, a new museum opened. Its context was a converted police station, but this was no memorial to the police of Sydney. Rather, Qtopia was inspired by the queer community who suffered in this station at the hands of the Sydney police.

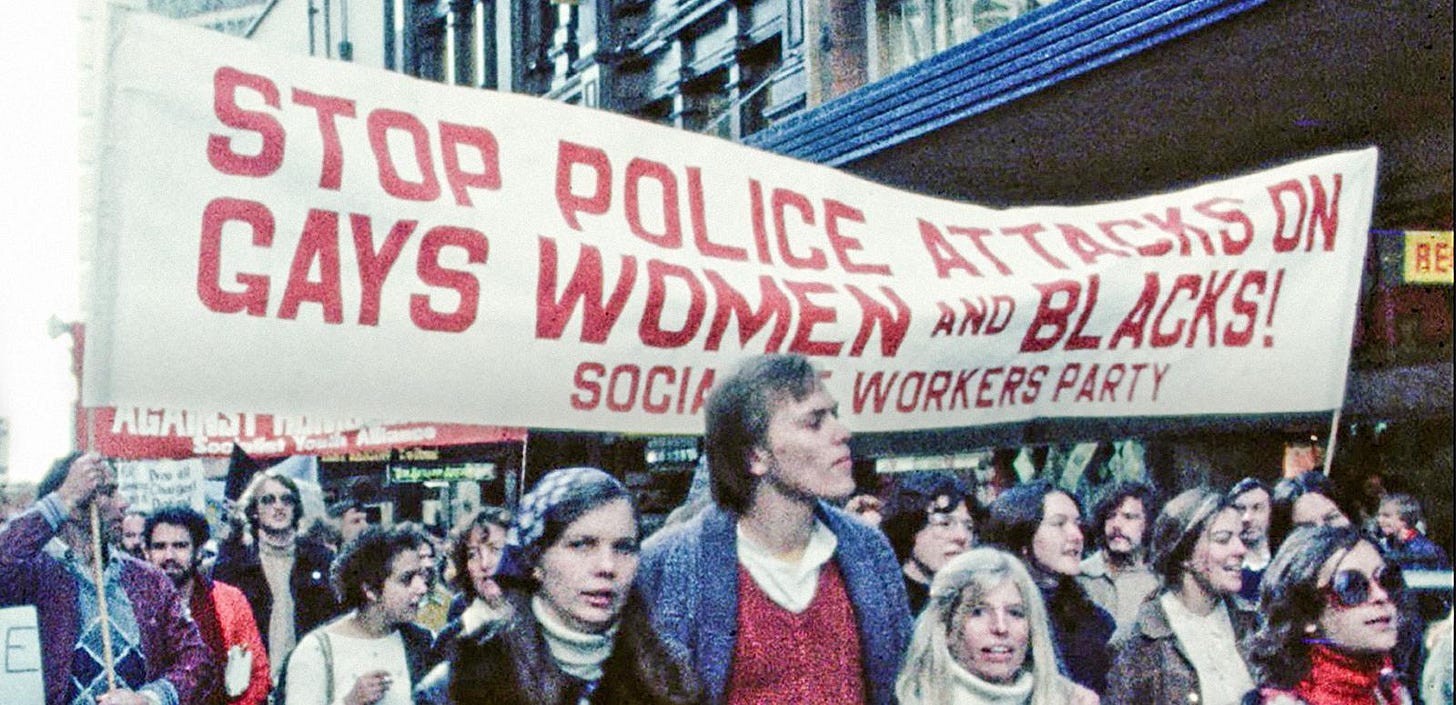

In March of 1978, members of the gay community of San Francisco wrote to other LGBTQ communities throughout the world, encouraging them to stage activities on June 25 of that year commemorating the Stonewall riots of 1969 and showing a unified front of support for queer rights in the face of the campaign of Anita Bryant and others like her to repeal anti-discrimination laws around the world.

Sydney’s queer community responded by staging the city’s first ever Mardi Gras parade on June 24, 1978. Approximately 500 people marched during the day. That evening, organizers also put on a nighttime celebration and parade starting at 10pm, in response to LGBTQ people who said they wanted to be a part of the event but were afraid of losing their jobs if they were seen to be marching in the day time.

What began as a fun event filled with costumes and great music went dark after the Darlinghurst police first confiscated the flat-bed truck with their sound system (though they had a permit for it), then blocked off both ends of the local road and began attacking and arresting people.

As at Stonewall in 1969, the crowds fought back, working to free those who had been thrown in paddy wagons. But in the end, the police arrested 53 men and women and took them to the Darlinghurst copshop (as police stations are known in Australia), where they were subject to violent attacks and inhumane treatment even worse than what happened in New York. In the museum you can visit the tiny cells where dozens of people were forced to stay together with no facilities beyond a bucket to urinate in.

The entrance to one of the cells large groups were imprisoned within.

The police of Darlinghurst copshop were already well known for their violence toward the queer community. There was an entire group of younger, handsome Darlinghust cops known as the “Peanut Squad” who went to queer cruising sites like the nearby underground toilet block and entrapped young gay men. The cops even had a physical attack they liked to use (and would use in 1978), the “Darlo Drop,” in which groups of police would throw a victim by the limbs at the ceiling of a cell and then watch them drop.

On June 27, the Sydney Morning Herald published the names, addresses, and occupations of those arrested, effectively destroying many of their lives. People were fired and evicted as a result. Some killed themselves. (It wasn’t until 2016 that the Herald to apologize for what it had done.)

Within months the charges against everyone arrested would be dropped, and by 1987 the Darlinghurst copshop was closed on account of corruption and the many, many horrible things that had been done there.

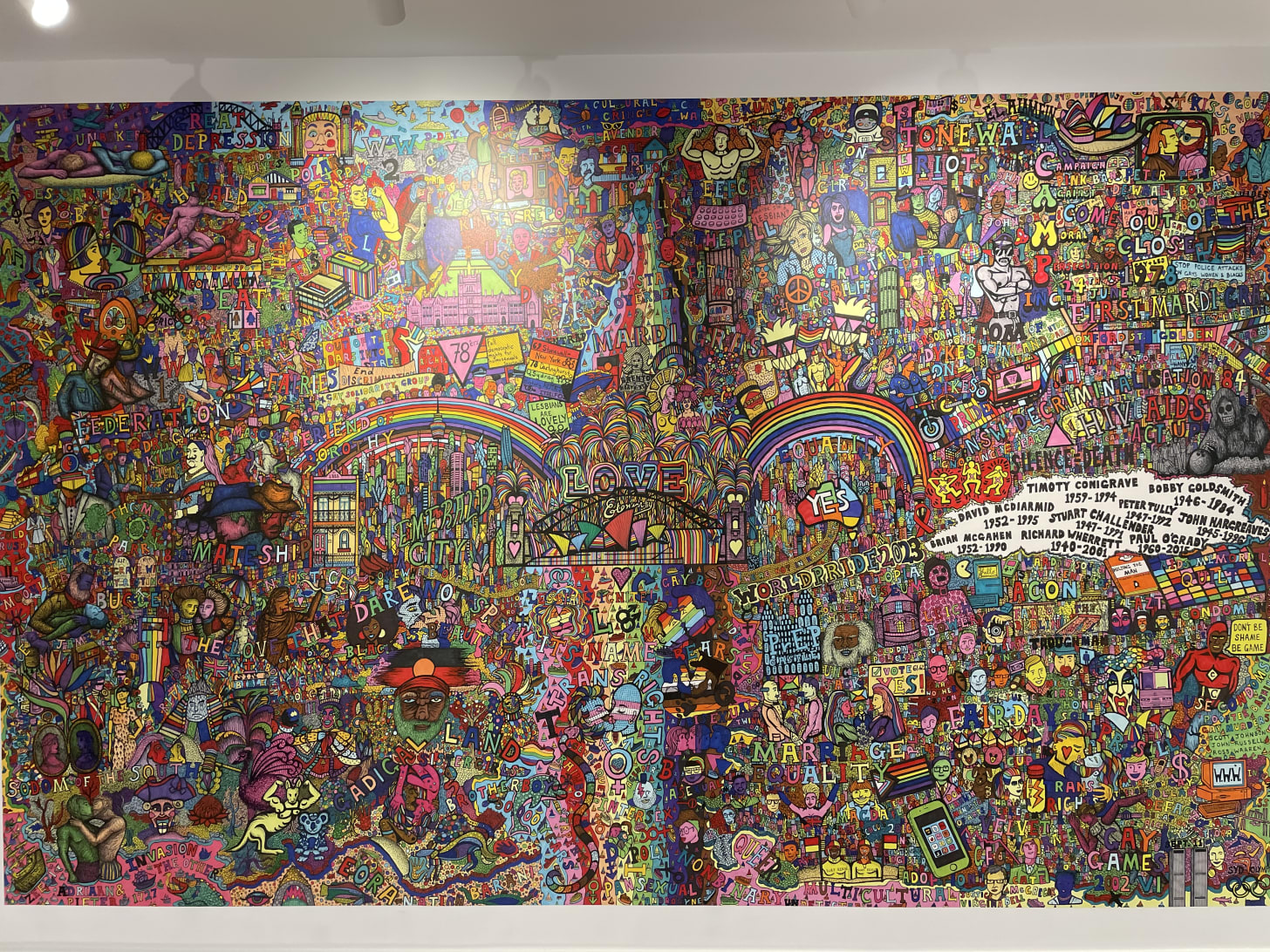

All of which is to say, it’s an extraordinary place to host a museum commemorating and celebrating the queer community in Australia (or anywhere, for that matter). And while it’s relatively small, it still manages to be split into seven very satisfying parts. One side of the main building commemorates the ‘78ers, as those arrested in 1978 are called. The other side hosts rotating exhibits, including right now a wonderful exhibit on First Nations queer people, as well as some really interesting artwork in the back, like this amazing mural by Jeremy Smith of queer culture.

Zoom in if you can. There’s so much cool stuff there.

At the front of the building, there’s also a beautiful remembrance of all the victims of HIV/AIDS in Australia, as well as a side room where you can sit and watch interviews with different prominent queer Australians. (I actually could have spent hours just sitting there; the conversations are enormously interesting.)

And across from the main part of the museum there’s another room which currently has a really powerful exhibit about the history of trans people in Australia. To see photos and read stories of people claiming their proper gender expressions upwards of 70, 80, 100 years ago, to witness to their courage just knocked me out. Check out this story from 1950.

Equally mind-blowing is the fact that in 1950 the journalists reporting this story showed more empathy and respect for Mr. Armitt than many journalists or news outlets do today.

In addition to the main building of the museum itself, Qtopia has turned a nearby building into an arts and performance space. And it’s taken the nearby underground public bathroom area which queer men regularly used as a place to hook up and turned it into a museum about cruising.

Today when we hear reports of people arrested for indecent exposure in bathrooms or movie theaters, the people involved are generally presented as disgusting. It’s a filthy thing that they’ve done. But rather than accept that badge of shame, the Qtopia Museum has reclaims and celebrates that part of gay history. Cruising in toilets and sex clubs was (and to some extent remains) an important way that queer people have found each other and a space in which they felt they could fully express themselves.

Qtopia asks that you don’t take pictures of the toilet block exhibit, so I can’t share any beyond this of the outside, which I think demonstrates how basic are the spaces the curators have worked with.

What I can say of the Toilet Block exhibit is that it’s one of the most eye-opening and meaningful queer museum exhibits I’ve ever seen, if not the most. As someone who came out late, it’s so inspiring to see an aspect of gay life that has often been characterized in such negative terms revealed to be something vibrant and joyful.

Qtopia has as a symbol a large Q over triangles of different colors. Those colors include both the colors that historically have represented different parts of the queer community, and others representing ethnic and racial communities to which queer people belong. And the overall idea is to create a stained glass effect. Stained glass so often is used to represent something of the past, like saints. And yet as glass it’s still something through which the light pours, something we look through toward the world beyond. Qtopia, the curators write, is meant to be a “window to the past that lights a path to the future.”

To me that icon and Qtopia speak to the heart of what a queer museum can be, and more generally what cultural and historical museums are for. We look back upon elements of our history not as an intellectual exercise, ideally, but so as to illuminate some aspect of our own current life experience. A museum is meant to broaden our understanding and make our lives bigger in some way, and perhaps more complicated, too.

That a queer museum in Sydney would be providing such a rich example of that makes a certain amount of sense. Queerness is literally the casting aside of the standard narratives of what is right or true given to us by social institutions in favor of people’s real life experiences, which are always so much stranger, surprising, and spiritually revelatory.

Thanks so much for reading. I know most of you are reading from the States. I hope you’re enjoying these little glimpses of Australia.