Ode to the Dancing Priest

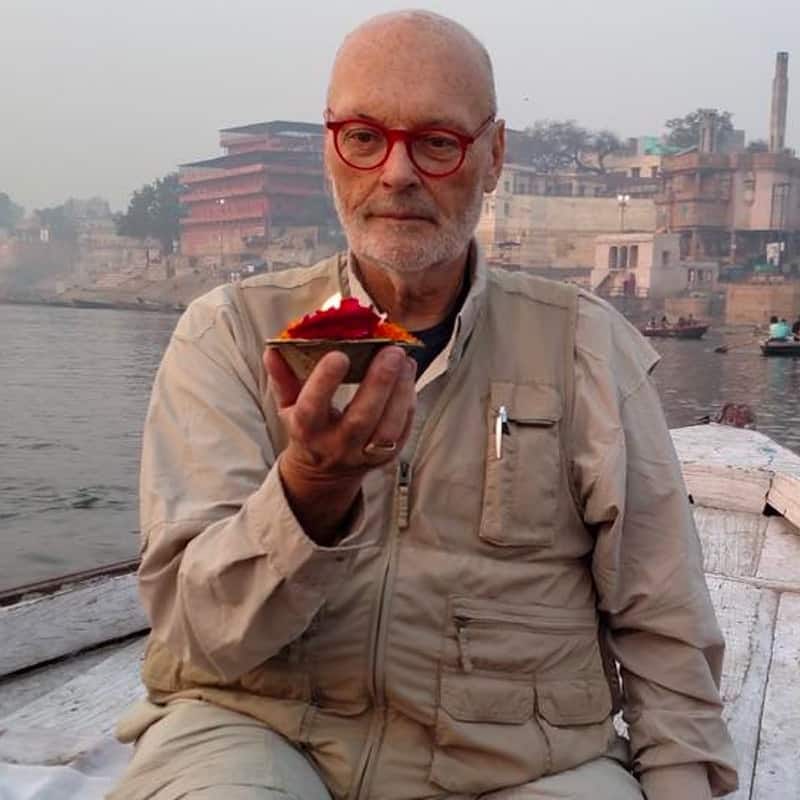

Tom "Tomaso" Kane, C.S.P., taught me so much about the priesthood, life and art.

I love to run into Paulists. There are plenty of reasons—they’re great priests, with very contemporary and thoughtful views about the church. Their sensibility about spiritual things seems to match up pretty well with that of a lot of American Jesuits. They’re also invested in using media to communicate the love of God to people, so much so they started the church’s most successful production company, Paulist Pictures, which produced Romero and Entertaining Angels: The Dorothy Day Story, and created the Humanitas Prize, which honors film and TV work that explores the human condition. Today it’s one of the most revered prizes a screenwriter can get.

But when it comes right down to it, I get excited when I meet Paulists because I get to thank them for Tom Kane.

When you’re studying to become a priest, you take classes on various practical parts of the priesthood. We had a class that was just about the theory and practice of hearing confessions. I had a whole class on the theology of the Eucharist, another on preaching, and another called “Rites” in which we spent the semester practicing the various kinds of liturgical ceremonies priests have to do, from your standard Sunday or daily Mass to baptisms, funerals, and anointings. I think one of us maybe did an Easter Vigil, which is basically the Sturgis Rally of liturgies.

And at Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Mass., where I studied, we were blessed with our own Holy Trinity when it came to liturgy and sacraments. Historical theologian Fr. John Baldovin combined a deep knowledge and appreciation for the history of the church’s liturgical practice and theology on liturgy with a wonderful pragmatism about how the church functions and our work as priests within it. Sacramental theologian Fr. Peter Fink brought the instincts of an artist to his similarly rich sense of the history of sacramental theology; he helped understand the underlying poetry of the sacraments.

And Tom Kane, who passed away at age 79 in Florida earlier this week, stood as the point of their triangle. In our classes on preaching or rites he had enormously practical wisdom to share about everything from style and structure of a homily to the way you should hold your hands when praying the Eucharistic prayer. (He used to tell us when your hands are out your fingers should be pressed together. Otherwise they just look odd. “Leaky grace!”, he’d tell us when our fingers were splayed.)

But at the same time Tom had a sense for the inherent drama and artistry of good liturgy and a life well lived. He had an apartment in Cambridge in the same building as many of the lay students, and it seemed like he was always having feasts, going out to the opera or theater with friends, and above all enjoying life.

Tom—or as he preferred, Tomaso—was known as “the Dancing Priest.” In the 90s he’d done a documentary series, “The Dancing Church Around the World,” which shone a light on the various uses of dance historically in Catholic communities around the world.

But I always thought of that nickname in a different way. When I knew him, Tomaso was a tall, heavyset man. And yet he had an incredible lightness about him when he moved. In a way it felt like he was always dancing. And his spirit was similarly infectious. Without trying, Tom made everything lighter and funnier and better. (And also a little more outrageous, in the very best sense.)

Tom gave me so many of the most important pieces of advice I ever got about preaching. Like, when you write out your homilies, or give talks, break the paragraphs into what he called “sense lines,” smaller units of meaning out of which sentences and paragraphs are built. For example:

Tom Kane was a great man.

He used to go to the theater,

But more than that,

He brought the theater with him,

And helped us understand the joy

Of a life lived big and wide.

When you split speech up into these poetry-like units, you begin to work with them in that way. The breaks help you find the richest means of expression.

Also, he told us, when you’re preaching, don’t explain everything. You’re not doing a dissertation defense or making an argument. You’re trying to invite people into an experience of God. In order for that to happen, you need to leave room for them to make connections of their own. So where you can, leave some gaps for them to fill in.

I would often think about that in terms of sections of my homily—If I had a story followed by an idea or vice versa, I would resist the impulse to let the idea simply be an explanation for the story, or the story just an example of the idea. Instead I’d try to let each piece be its own meaningful unit or little experience, and allow the listeners make whatever connections they wanted.

(Tom also told us, if you notice that people aren’t paying attention, don’t freak out. The point of the homily isn’t that they lap up every word that you say, but that you enable them to find some way to connect to God. What looks like daydreaming to you might actually be your mission, accomplished.)

As I look back, Tomaso’s ideas and appreciation for preaching and presiding made me a student of liturgy. Even now when I’m no longer presiding myself, I think a lot about how one does liturgy and considering the practices of others with the curiosity I would bring to a play or a great work of theology.

Any time I meet a Paulist priest, I get excited because I get to tell them that their Tom Kane taught me how to preach. I’m sure at times they’re a bit bemused by my enthusiasm. I mean, what do you say to that? Neat?

But stepping back now, I think what I mean each time I’ve said that is that before I even was a priest or knew what that work would mean to me, Tom planted the seeds that would enable me to see every element of my work as a presider, from the way I poured the water over the baby’s head to the length of my homilies as a moment filled with potential, a chance at revelation and blessing and beauty and laughter and grace. Without ever saying so, Tomaso taught me and so many others to see our work and our lives as art.

What a gift that, and he, has been.

I’ll be back on Monday. Have a great weekend.

What a brilliant legacy, amazing blessing and beautiful testimony for a mentor. Jim, thanks for introducing us to Tom. 💌

Godspeed, Father Tomaso!