About a year ago I was in Cambridge, Massachusetts wandering old haunts, i.e. its many book stores. And at the Million Year Picnic, which is by far the best comic book store in Cambridge, I came upon this.

I don’t know how much you know about Barney Frank. He was a congressman for Massachusetts for 32 years. He was well known for his devastating wit, his lack of flashiness and his absolute commitment to mastering the issues affecting his constituents.

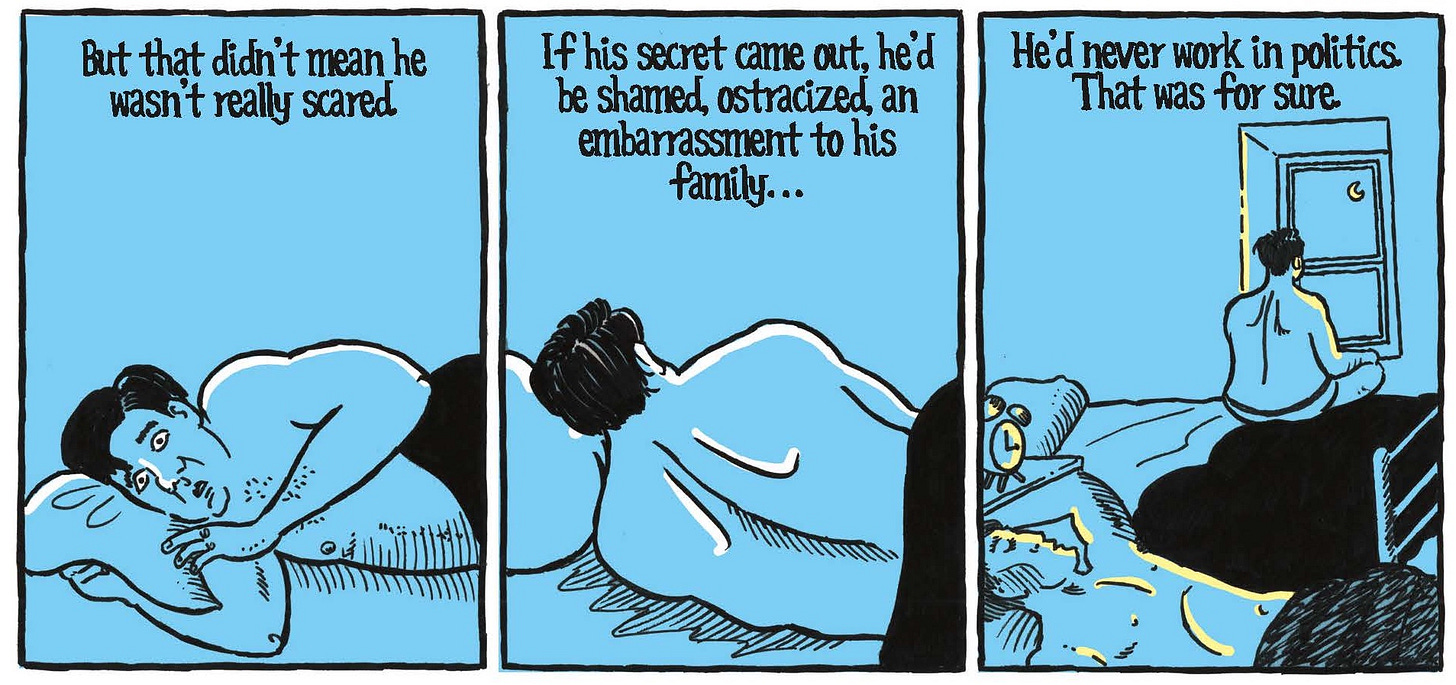

Also, he was gay. Frank came out in 1987. He was the first congressperson to come out (although not the first openly gay congressperson—that was Gerry Studds, also from from Massachusetts, who was outed in 1983).

After he retired, Frank wrote a memoir called Frank. And it really affected me. It was his story along with those of a couple others that really started me wondering whether there wasn’t some way to be more open about my sexuality as a priest.

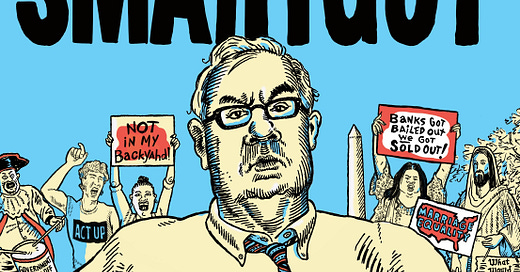

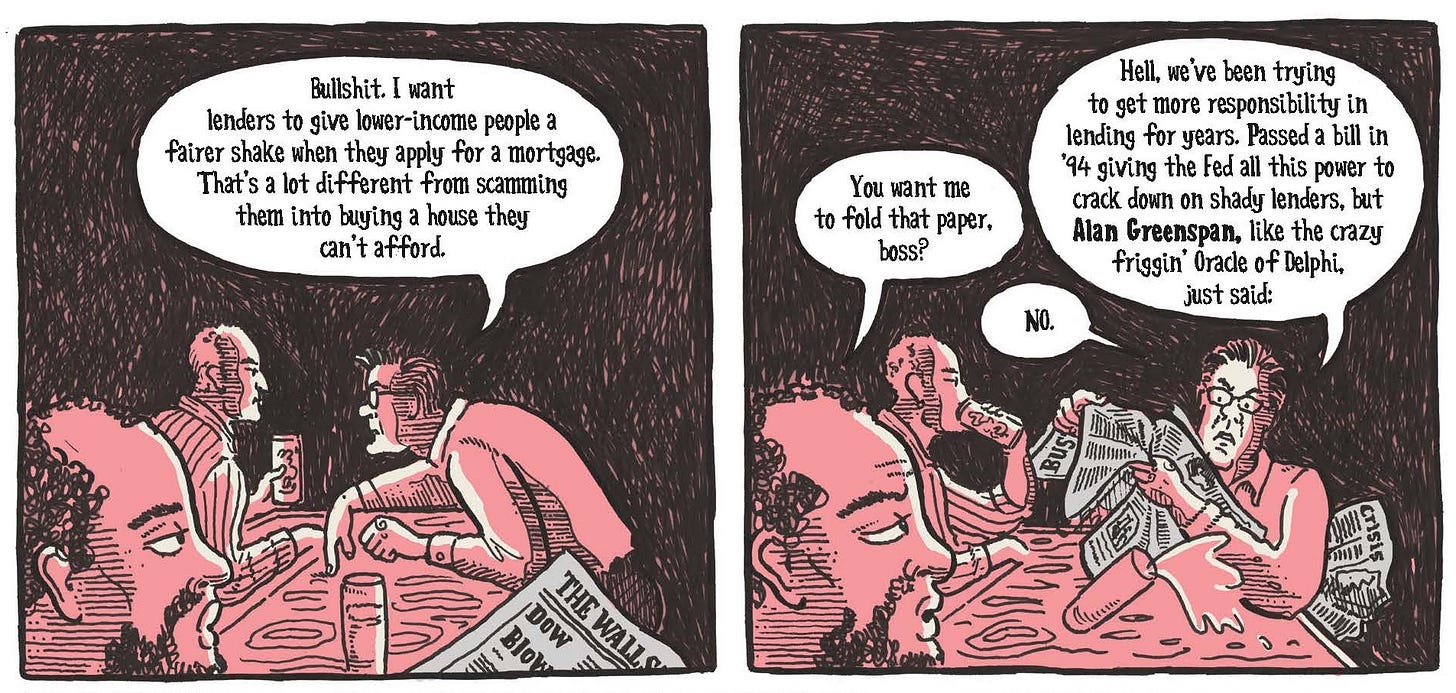

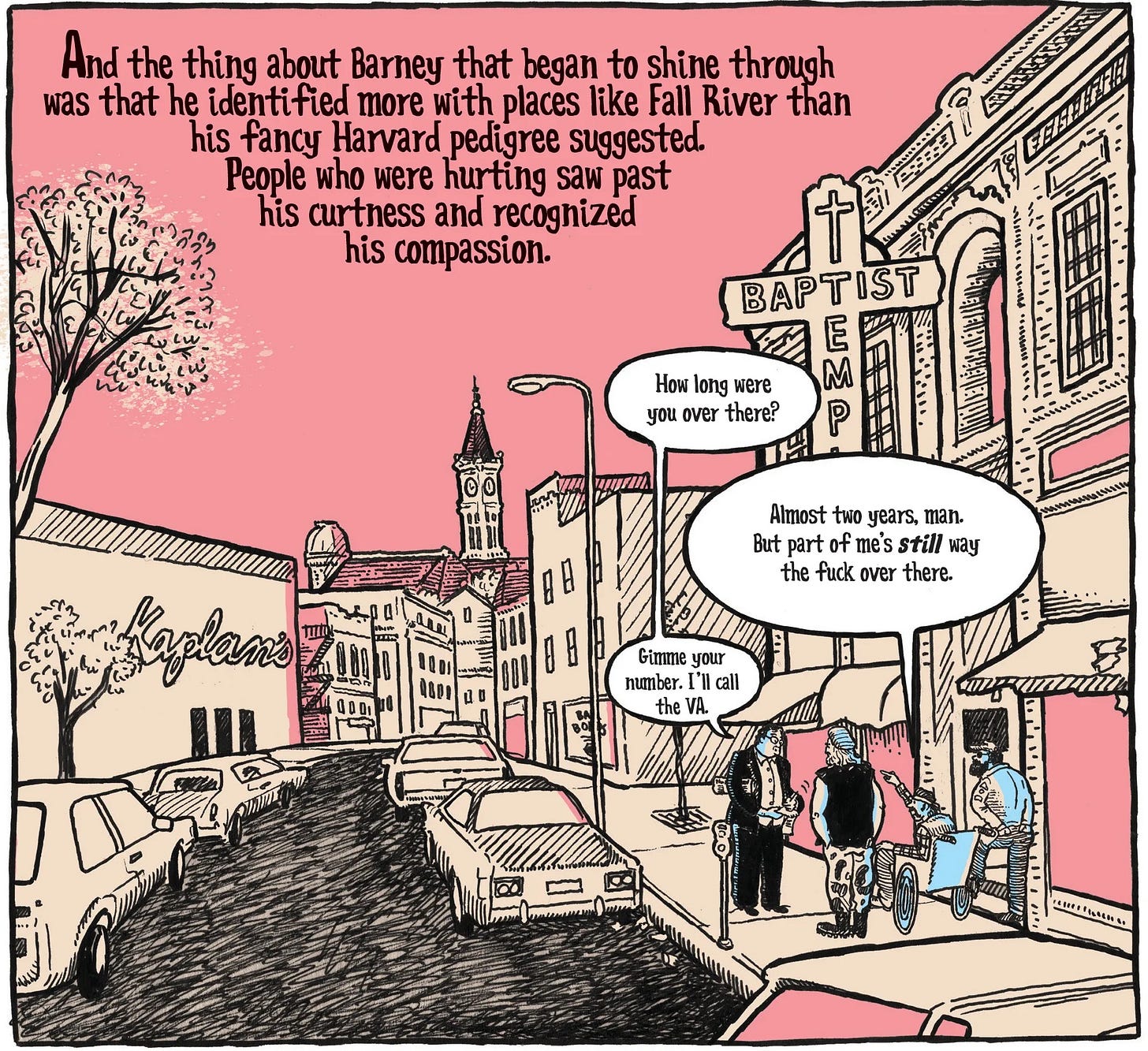

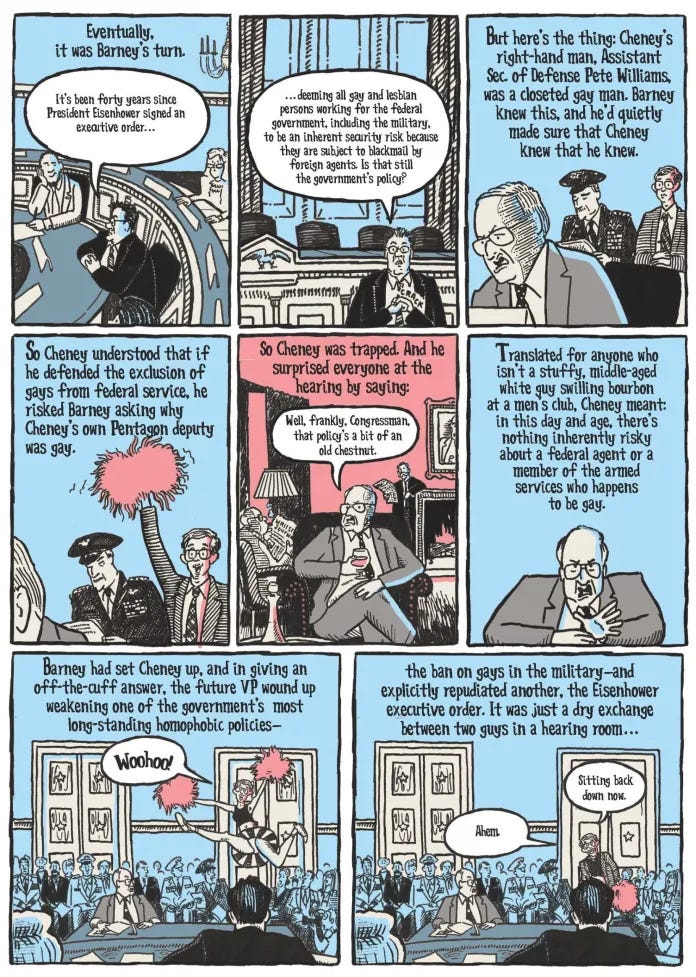

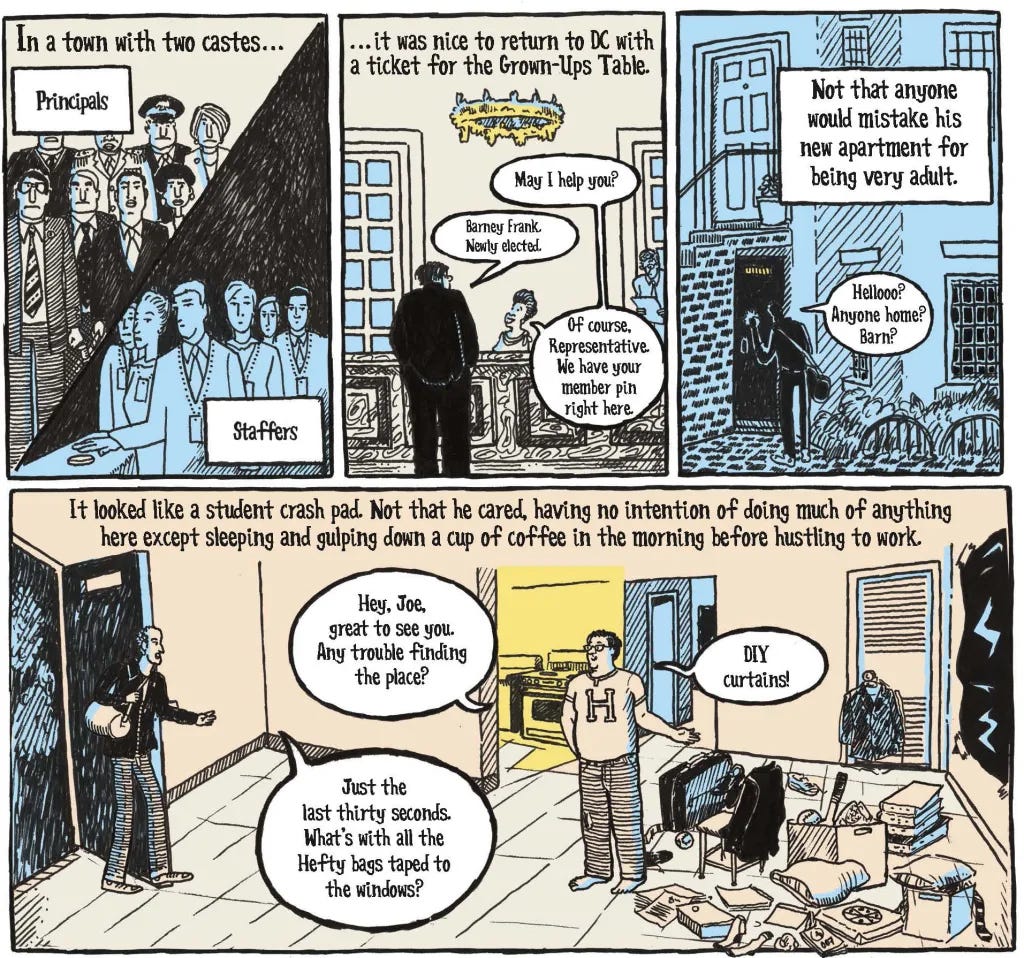

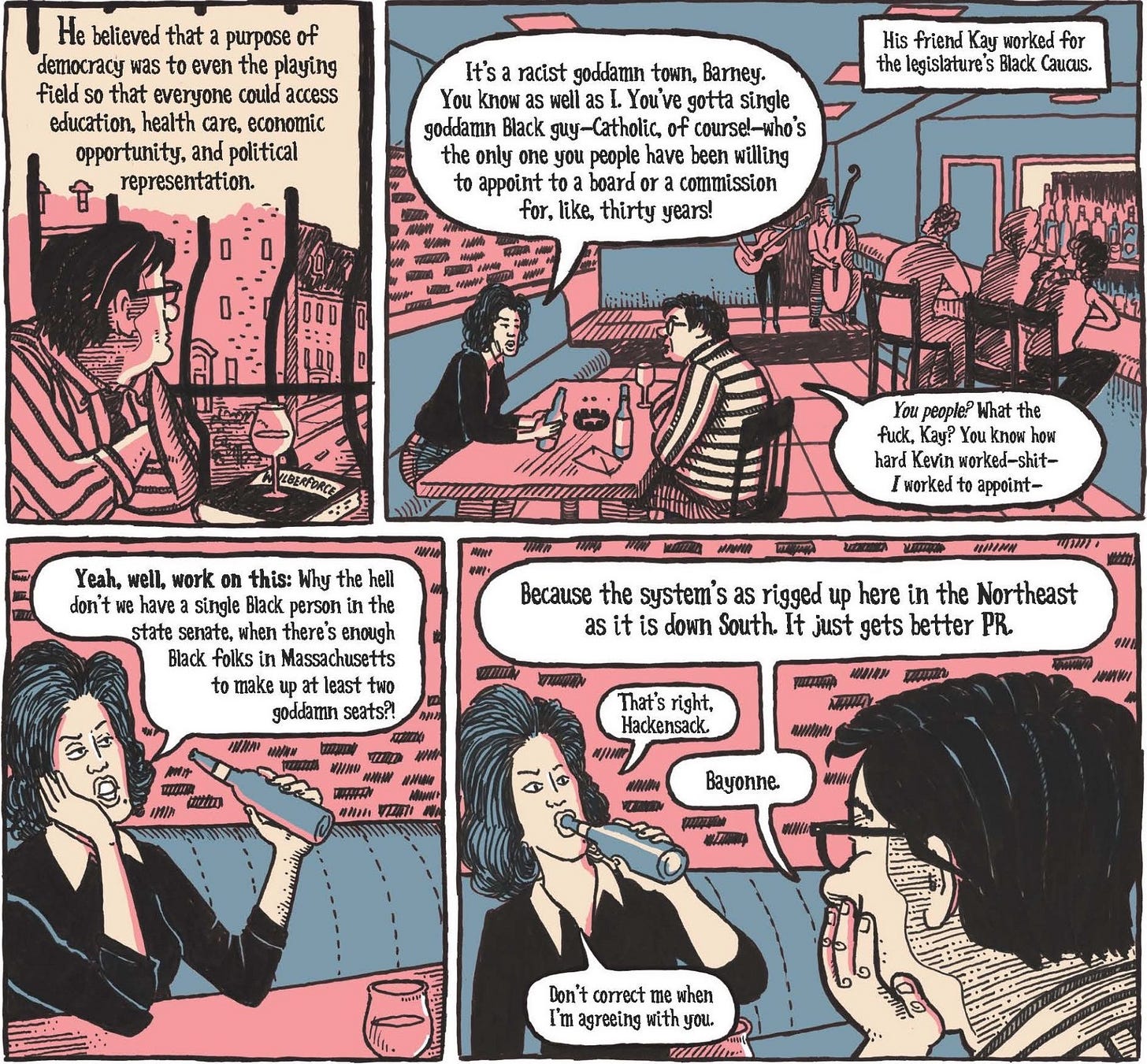

Suffice to say, I snatched up Smahtguy. Written and drawn by Eric Orner, a cartoonist who for many years drew a popular syndicated comic strip about gay life called The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green and also worked as a staffer for Frank for some time, the book sets out to tell the story of how a Jewish kid from Newton became one of the great congressmen of our country, and also how a shy gay man eventually took the risk of coming out. It’s a really surprising book. Orner, like Frank, believes there is great drama to be found in social policy, and consequently he’s happy to dive into some of the issues that Frank was passionate about, like housing or the economy. But the book is filled with pathos, too. In fact for me reading it was like watching a great magic trick. No matter what Frank is up to politically and professionally, we never lose track of the man behind the scenes who is by turns terribly lonely, afraid, and slowly trying to reach for something more.

There are many great paradoxes to Frank’s life. He became more comfortable and confident being gay once he became a congressman, despite the fact that his life was now going to be under greater scrutiny than ever. A lot of constituents were ordinary people who he might have imagined would not be comfortable with him being gay, and yet when he came out there was no great backlash.

Orner captures all of this with a great eye toward not only the mind and heart of Frank, but the underlying humor, intentional and otherwise. (The look on his face as he’s made to hold that crying baby…*chefs kiss*.) Frank’s general disinterest with his appearance, his acerbic wit and the humor of his staff, who regularly remind each another, “You have to love Barney in order to like him,” all feature prominently. And Orner’s cartooning approach proves to be a perfect match to the character of Frank.

I loved the book, which is available on Amazon, so much, I reached out to Orner for an interview. I love talking to people about their work, and I have to say this conversation, which ended up being not only about Frank but Chicago politics (we’re both natives), cartooning, growing up gay at a time when that wasn’t allowed, and the idea of democracy, is one of my favorites. I hope you enjoy it.

I call this “Longform Wow," and as you’ll see, that’s an accurate description. Personally I love a deep dive like this. I hope you will, too.

JMcD: About five years ago, after a lot of years as a Jesuit and a priest, I found myself beginning to feel like there was something not quite right about the way I was living my life. Barney’s book Frank really helped me think about the juxtaposition between my private and public identities. I didn’t know much about him before that.

EO: Where are you from?

The northwest suburbs of Chicago.

Oh, you’re kidding, I grew up in Chicago. My mother’s from Boston and my father’s from Chicago. I grew up in Chicago, but I went to college in Boston. (And then, because cartoonists have trouble making a living, I went to law school in Boston.) So I really have dual citizenship as a Bostonian and a Chicagoan.

Ha ha ha.

The funny thing is, now I live in New York City, the one place that Chicaogans and Bostonians, who are nothing alike, agree on their antipathy towards. I’ve spent the last 10 years here. When people say where are you from, my partner will elbow me and say Just say New York, but I can’t do it. It catches in my throat, I don’t know if it’s a Bostonian thing or a Chicagoan thing. I don’t mind saying I love it, it’s a magnificent place, but it’s not mine.

Did you grow up in Chicago proper?

I went to first grade in the city, I lived on Schiller, near north, then my parents decamped to Highland Park. But both my folks were very politically active in the city, very socially active. My mother is 85 years old, and sometimes she’s going up and forth on the train twice a day, like for a meeting and then at night. And that’s sort of how they’ve lived their lives.

It’s funny, because of your name and the fact you’re a Catholic priest, I assumed you were a Bostonian.

I spent four years in Cambridge; the Jesuits used to have a theologate right next to Harvard. I loved it.

That rings a bell. I lived just outside of Harvard Square for 10 years. I think I’m a Bostonian, but really I lived in Cambridge in a great old rent-controlled apartment. Those were some of my favorite years.

Smahtguy really moved me. Even as it’s a story very interested in the policy and political questions of Barney’s life, it never loses track of his personal journey.

Thank you very much. It was very important to me with Smahtguy not to simply string together a series of legislative achievements and call it a biography. The humanity of it is what interested me. It would have been interesting whether the guy was a race car driver or a politician. But it happens that I’m an old political cartoonist, those are the stories I gravitate towards.

I’d love to do the same thing for Jane Byrne, who always struck me as just operatic in scope, with an incredibly unlikely story, and she’s basically forgotten. I mean, she’s not forgotten in Chicago, but she doesn’t get the credit. There’s the pathos of her whole up and down political trajectory.

That’s funny, I’d love to write a screenplay about the columnist Mike Royko. He’s a Chicago hero of mine. Like Byrne, he’s such an important figure to the city, but people don’t really talk about him any more.

Oh absolutely. The story of his significance at the time, the influence he wielded…you can absolutely imagine a biopic about Royko. He was the first thing you turned to, he was the first thing that everybody turned, especially in the Daily News. But in the Sun Times, the Tribune too.

At the moment he’s not remembered, but it’s such a good story, easily retrieved.

It would be the same with Jane Byrne. Her story is right there waiting.

That’s what occurs to me. This big city mayor, came from nowhere, just a widow who had the balls to find Mayor Daley, who didn’t know her from Adam, and became his confidant. And inspired ferocious jealousy from the next Mayor Daley, and all the other men in the city, because she was talented and funny and had that incredibly irascible temper which eventually did her in.

She was unfathomably tough. If they remember it all, people remember it as a stunt when she moved into Cabrini Green [one of Chicago’s most troubled housing projects]. But it was no stunt. There were pictures of her getting in here little petticoat kind of nightgown, going out to the front of her hallway to pick up her newspaper.

There’s this famous quote in the Sun Times the day she won. She said, “I beat the whole goddamn machine.” The long knives were out for her, and eventually they got her. But not before she got them.

There’s a movie right now, The Lost King, about Richard III, the reviled king, the subject of a famous Shakespeare play where he’s a horrible hunchback. He was a Plantagenet and the Tudors, who defeated him, then had a hundred years running the country. So they wrote him out of history. That dynamic repeats itself in history all the time.

Byrne represented such a challenge to the Daleys’ authority. And it was coming from the old man, who maybe wasn’t all that impressed with his eldest son Richie, so he elevated this outsider. She was Irish, she was a cute-looking Irish Korean war widow, so she was well positioned. And it was all operatic.

The other book that I have cooking right now is a kind of memoir, but also a kind of biography of the Jimmy Carter years.

Wow, those both sound fantastic. Good luck with them!

Thank you. I wish you well on the Rokyo thing, too.

I think visually. And when I think of Royko, you think of him on a street in the slush, in the elements, with some sort of Columbo-like raincoat flapping in the wind, completely engrossed in what he’s writing, completely at one with this city, but out there in in it. I don’t know if that would be the opening shot, but that’s what goes through my head. You want to talk about Royko, the first thing you do is you see him under the L-tracks at State Street or something or out in front of that bar he liked, Billy Goat’s Tavern, except the old one under Randolph Street, in the slush.

His book Boss is incandescent as political storytelling. Believe me, I had it right behind me when I was writing Smahtguy. It was very instructive. How do you keep this interesting and keep it moving? There’s a few political books like that—maybe All the King’s Men, about Huey Long. And I love William Kennedy, who writes about only Albany. He’s brilliant.

As you were trying to put Smahtguy together, were there either principles you had or insights you discovered along the way about how to keep the story emotionally grounded and compelling?

Yes. But in saying yes I don’t want to say that I did it successfully. I learned a lot. I think I did some things successfully, and some things, in a next book, especially a next book of a similar type, I would apply those lessons even more rigorously.

The first one is: A lot of people say, it’s a big book and it’s comprehensive. But it’s not comprehensive at all. It’s no great intelligent thought, but I learned that a bio really is just a sampling of what went on in a life. You have to pick and choose your moments.

And that’s very hard. Because you feel at every turn that in not including something you’re leaving out some essential element. You don’t know that it’s essential, you just have this nagging fear that it might be. It’s not essential enough to you, that’s why you’ve made the decision not to include it, but then you second guess yourself and believe me, every reader on the planet does too. Why didn’t you write about this? Or I’m sure you’re writing about that. And you’re thinking, I’m not writing about that because it doesn’t fit into the arc that I’ve created. A lot doesn’t fit in, some of which you use anyway, and that’s another thing. What you don’t use haunts you, and what you do use, you second guess.

I wrote this comic strip The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, which wasn’t political. But before that, my hope was to work my whole life as a political cartoonist. Unfortunately in daily newspapers those gigs dried up largely, and I wasn’t going to wait around forever for that opportunity. So I’ve done other things with my life. But I’ve always cartooned. In a way doing Smahtguy was going back to what really interests me after 20 years of writing about gay people. Because I am one.

Did you feel like doing Smahtguy was bringing together these two aspects of your life—queer storytelling and political cartooning?

That’s what it felt like. I think a lot of the fans of Ethan Green, however many there are, were disappointed. They don’t think of me in this context at all. They think of me as telling smart, sassy stories of gay life, and don’t know that I had this different background.

So yeah, drawing Smahtguy was in some ways like, Wow, these are things I expected to be drawing about for the last 20 years, stories I expected to be telling but never got a chance to tell. Telling Barney’s life story did open up that opportunity.

Would you say that the years that you’d spent on Ethan Green influenced the way that you told Barney’s story?

Yeah, I think it couldn’t not.

There were two models for Ethan. One is very well known, Tales of the City, a serialized newspaper column about the lives of gay people in a city that the writer clearly loves. That’s the obvious model.

The other was called Bag Time. It was a serialized column in the Chicago Tribune in the 70s and maybe the 80s when I was a little kid by Bob Greene, who was a reporter for the Tribune. Bag Time was about a nice guy in his 20s who worked as a grocery bagger at the Treasure Island grocery story, which was a fancy grocery store by Sandburg Village back in the day, probably gone now. And in Bag Time the hero, whose name was probably Bob, I can’t remember now, was a thoughtful, intelligent, writerly kind of guy who understood that he was just a bag boy, so he didn’t rate in his tony neighborhood. But he had a lot of sexual prowess that was known in the neighborhood. So these ladies on the Near North Side, busy anchor people and fancy lawyers and cardiologists and whatever, somehow this guy that works at the grocery story is what they’re all thinking about. And he’s a little bit embarrassed by that, it’s just because of his looks. But he’s like this is my only asset at the time.

Anyway it’s thoughtful, and weird, and about sexual politics and trying to hold onto your self worth in a world that wants to take that away from you. It was storytelling about sex, just like Ethan was about sex, but really about trying to survive as a young man in the city. That very much influenced me writing Ethan.

[Bag Time was collected into a book written by “Mike Holiday,” the fictional bag boy from whom Greene said he was getting letters.]

Nobody would even know what I was talking about now but because you’re from Mt. Prospect I mentioned it.

Did you see anything of Ethan in Barney?

Yeah. For a lot of us, we didn’t make our way as gay kids. We made our way in some degree or other of passing. There was no social structure to come up through boyhood, emerge into manhood as a gay man. That wasn’t an acceptable thing.

And Ethan to me was about somebody who had made that choice. Alright, I’m going to have to be a gay man, and I’m going to try and have a good life anyway. And what happens to him after that choice is made.

I mean, people don’t think this way any more, but I think it’s what people of my generation experienced, and certainly earlier. And I think Barney, even though he’s a different generation from me, he was late in coming out. So I see some of the same trajectories and struggles and grappling with issues.

There’s also a much more superifical thing that holds the two together. Ethan wound up running in about 120 newspapers, but it began in Boston. I started to obscure that later because it was like, I’m running in Houston twice a month, and I don’t want these Houstonians to think Oh, he’s not talking to me. But early on it was really about gay life in Boston. And of course that’s Barney’s story.

I’ve been rereading Smahtguy, trying to understand how it works. Because it has a ton of story and policy conversation in it, yet the heart is always there.

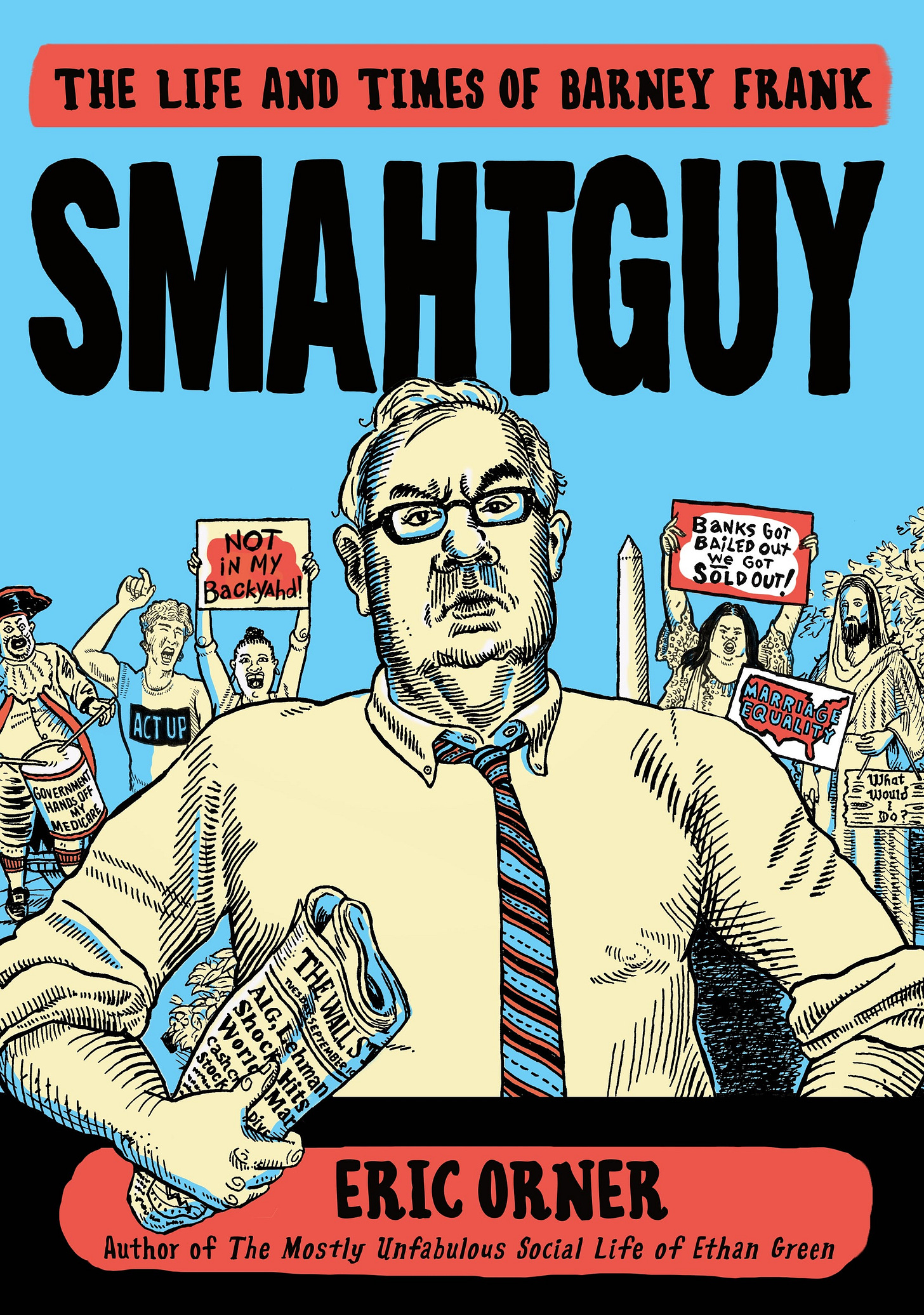

That’s a relief. I’m interested in politics. I’m convinced that I can make it interesting to people. But the most important panels in the book to me are a picture of Barney walking late at night after seeing a movie alone. Or in DC, when he’s much more powerful but still just as lonely, walking through one of these long fluorescent corridors in the Capitol or flipping through a gay rag against a rainy window at home. It wasn’t hard to keep sight of the fact that that’s who this person was, right after he finished being powerful and banging the gavel and doing what he did during the day.

Those are exactly the moments that I’ve kept going back to.

There’s that idea in storytelling that if you give the audience a problem early, you don’t have to keep hitting it over and over. They will carry it for you.

I thought you did that so well. You set up at the beginning that this man is going to put himself in this position where he’s going to work in government, but he’s trapped in the closet. And so even as he’s doing all this great stuff for others, I’m constantly thinking, but he can’t do anything for himself.

I’m very appreciative that you think it works. There are days where I think it works and there are days where I look at it and think, Well, next time I’ll do better.

Did you find that doing it in a cartooning style was an easy fit with Barney’s life? Were there parts of his story that turned out to be challenging to draw?

It’s weird. When I see something I want to draw it. That’s how I translate it. That’s what’s going on in my head.

And I think that a lot of people who like comics might wonder, Why apply comics to the real world? For me, my cartooning is real world-based but I allow myself flights of fancy that lend themselves to illustration.

But it was a challenge to take what is basically landscapes that are not dramatic, making fluorescent-lit government spaces and tired old city streets, making that visually interesting, and more than that conveying somehow a love of these spaces. It’s not like I’m drawing the Grand Tetons, I’m drawing a conference room in Boston City Hall.

But these are the places that I like, that interest me. And the things that go on in them interest me. Making a boring social security office a place of visual interest is a challenge I like.

So I wouldn’t say Frank’s story lends itself to cartooning, but maybe I should say it lends itself to my kind of cartooning.

I see that in particular in the differences between Boston and Washington, the depth of humor that I think exist in Boston and the dearth of it in Washington. To convey that visually—I’m not saying anybody else is interested in it, but it interested me.

Two examples come to mind as you’re talking. There are the scenes in Washington, where Barney is talking politics in a gay bar. I found those moments unexpectedly moving.

I always worried that I was giving more visual attention to Boston. And yet I spent a lot of time in Washington. Many of the cartoonists I know now teach, but that was never my thing. Other than ten years working in animation, I’ve had day jobs, mostly communication-oriented, government speech writing.

And the spaces that occupy those lives, I wanted to depict. I’m glad that a Washington space resonated with you, because those were harder spaces to convey the love.

I’m thinking out loud here, but I think the way you did it was by way of the community of people that you show Barney becoming a part of. There’s like a growing wholeness or integration of the two parts of his life in the fact that he’s having these political conversations in a gay bar.

The strongest characteristic of Barney’s story in Boston is loneliness. That is not the strongest characteristic in Washington. In Washington he was becoming more whole. It was an effort, there were big setbacks. But he was people-d in Washington. This person was learning to have a social world in Washington. So the city itself recedes as a character.

In Boston there’s a lot more depiction of landscapes, because that’s what a solitary person notices. But when a person isn’t solitary any more, when he’s going out to bars with his friends, he’s in spaces where you can’t even see the landscape. You don’t know what the bar looks like because it’s filled with people.

So people become the most important graphic element. It’s true whether you’re in a hearing room or a crowded cafeteria or a gay bar, those Washington scenes are filled with people, and not filled with the architectural detail that I like to think about when I’m drawing Boston.

The other thing that comes to mind is how each chapter begins with a double splash of the new setting of the book. Those pages leap out. They’re gorgeous.

Thank you. I think there are more innovative artists than me, but I do love to draw. And sometimes you sort of swing for the fences and think well, other people could draw this better or more beautifully, but this is what I’m feeling.

That’s what you get from them, you get the feeling.

That’s nice. A few months after I got this book deal, I got this artists fellowship, this place called Civita in Italy. They fly you out there, they give you a studio, and you work on your project for 6 weeks. It’s quite a heady thing. And I had finished writing, I was ready to start drawing, and you know, even for somebody that’s used to having a weekly deadline for a comic strip it’s like, Where to start?

An artist I know here in New York said, Why don’t you start with some big pages, some big layouts that suggest to you what this is going to feel like. So those big layouts were the first things I did. And they did somehow guide it emotionally. There was something a little austere about the Washington spread, something lovingly detailed about the Boston spread. They sort of set the tone emotionally.

A lot of the story is very paneled, 6, 8, 9 panels per page or more. Then suddenly you’d open up onto a moment like this, and it felt like maybe you were giving us a taste of what Barney really wants, which is a much bigger life, a life rich and full. It’s like we’re being given a taste of where he’s headed.

That’s an interesting thought. One of the things that I wish I had been more innovative about was page design. But at the same time, I’m loathe to inject any sort of inventive design that disrupts the freight train of story that I’m trying to generate. So a lot of times I would think, Ah, I could be more interesting design-wise. But is it in service of the storytelling? And I would pull back, except for those spreads. Maybe next time I’ll be braver.

It’s like, you decide what your foremost value is. The filmmaker Tim Burton, I always think Okay visually this is stunning, but storywise, like, What the hell? I didn’t want that. So I kept it maybe in my estimation even too conservative when it comes to design. It’s something I’d like to work on next time. But I do not want the design to interrupt the propulsiveness of a story. It’s a hard needle to thread.

You said you see things and you want to draw them, that’s how you translate the world. When you worked on staff for Barney, did you find him like that? Was he someone you met and thought, Oh I’ve got to draw that guy.

Oh, definitely. I met Barney because I was publishing a lot in the Boston Phoenix, and then I was publishing Ethan, and in the early years it was pretty obvious that it was about Boston. And I had written an Ethan strip where I was very critical of Boston’s archbishop, Bernard Law, who was egregious in his nastiness about AIDS. And so he would show up in Ethan strips where I would take swipes out of him.

This is very early on. I did Ethan for 15 years; this was in the first 6 months. And at some point I was in the same space as Barney and I introduced myself and he knew the name. He was like, Oh, you draw those strips where you’re making fun of Cardinal Law.

He said, I’m not under the impression that cartooning pays very well. If you ever need a job, call me. And I was an art director for a magazine, but the magazine wound up folding, and I did call him for a job.

And he was such a character—I mean, I admired him, I admired him incredibly, I admired his wit. The first time I ever knew who he was, I was in college and he was on the radio saying the right to life’ers seem to be believe that life begins at conception and ends at birth.

But to make a long story short, I draw everything. I always have a sketch pad and I’m always drawing. Even when I was working as a political aide, I’d have a sketch pad, and if something would struck me as funny or weird or unusual or cause for having an opionn I would jot it into a book. And this is like ’88, ’89. So yeah, when this project happened, there was a lot of old notebooks to draw on. *laughs*

That’s amazing.

Yeah. And he struck me as funny. I sometimes worry that wasn’t conveyed enough in Smahtguy. But the thing was, I didn’t want to be a character in Smahtguy. So some of the funniest interactions I’ve actually had in life with Barney aren’t in Smahtguy.

I liked how in the book as a human being he seems a bit all over place, kind of messy and totally disinterested in that fact. The scene would be about something else, but his shirt would be untucked or his papers would be dropping all around him. I thought that was delightful.

I always thought that was delightful, too. And not to sound too full of myself, but I think the electorate found that delightful. They were like, This is a guy who doesn’t look like he cares about anything other than working for us.

There was an appeal to that. Remember this was an era of Kennedy and then Reagan glamour. To have a politician that looked like he rolled out of bed, and can’t be bothered to even like, acknowledge it. If you try acknowledging it to him, he’ll wave you away, because why are we talking about that kind of bullshit when we have home heating oil to get to people. He was prickly as all hell but there was an appeal even when he was being prickly.

He went through a phase—this is the sort of thing that I don’t have in the book—where he stopped saying hello and goodbye on the phone. Phone calls with him, which were always abrupt, because more abrupt, because he had made a calculation that the five seconds on the one end and the five seconds on the other, multiplied by the 200 phone calls that he makes during a day, equals x hours of taxpayer service that he’s not providing.

So it would be like you’d get a call and pick up and he’d start talking and then when he was done he’d just hang up.

Yes. He’d start talking, and boy, you better…A lot of people who worked for him would record him, because he’s not easy to understand anyway. Like Talmudic scholars we’d all have our ears to the recording device to try and figure out what he just said. People would be furiously taking notes. And right, he’d launch and then the phone would bang down.

Because you knew him, was it hard to present the portrait of him that you wanted? Because it’s interesting, I’d say Smahtguy both is and is not hagiographic. I think you’re pretty willing to show parts of him that some subjects might want airbrushed away, and yet the book is hagiographic in that the end result is somebody you care about.

I agree, somebody that I care about and somebody who I admire. But somebody who can be personally very challenging and unappealing. Unappealing in the immediate sense, not in the longer sense.

I wasn’t worried about it being too hagiographic. I was committed to warts and all. And also to just showing the scandal up front, and sort of depicting not just the struggle, but how unpleasant a lot of it was for him. Again the loneliness, the people who didn’t treat him well, being out there in a competitive world of gay dating and being not treated well.

Would you say doing Smahtguy gave you any new insights into Barney, or being gay, or our country?

The insight it gave me artistically is something we all know: Visual storytelling just becomes more and more powerful. And in a way I regret that. I don’t read as much as I used to, because I watch more. But I like making the pictures so it’s like I’m stuck with that.

Politically, I think that he’s one of hundreds of people who have been on the political scene since the country was founded who genuinely believe in a more democratic society, not in the sense that we cast votes, but in the sense that we do something to not just level the playing field, but to endeavour towards a society that is not so wildly unjust. A society that is not the sort of capitalist society that seems to just shrug and say, Hey, that’s the game. Everybody can take their shot, but there’s unfathomable inequity. Live with it.

And I think there’s people starting early early on who have bristled at that. Can’t we have democracy without this notion that the resources of the country and of the planet can be so wildly unequally divided?

American democracy is sort of an epic battle. And this’ll sound puffed up, but it’s sort of a privilege to get to tell the story of one of the combatants in it.

That really crystalizes something for me. Barney’s not a trojan horse; you really invest in his story. But he also brings with him all these questions about what is our country, what does our democracy look like, what is a good society, which you then get to talk about.

I agree with that. I never thought of this as just a bio of a congressman. He was a combatant in an endless struggle in this country for a lot of things that I care about. And that’s what I wanted to write about. Am I interested in him? Absolutely, but because he was in the thick of so many of these battles.

It sounds a little puffed up to me, but I think it’s true.

And I could make the same argument about Jane Byrne. The fact that she gets absolutely no credit, she’s not remembered, I don’t even think she’d describe herself as a feminist, but she was elected before Margaret Thatcher to a city we both know, and we know how brawny it is. And it may be forgotten at the moment, but that meant something.

Thanks again to Eric for taking the time to talk to me, and for such a fantastic conversation. I really appreciate it.

If you liked our conversation, please, support Eric by buying his great books Smahtguy or The Completely Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green.

And if you’d like to support me so I can do more interviews like this (I have some big ideas), my paypal is paypal.me/jimmcdsj. My Venmo is:

Thanks so much. I’ll be back Monday morning with the usual Pop Culture Spirit Wow!

Dang. Barney Frank, Jane Byrne, Mike Royko and Bagtime in one interview. What a great blast from the past. I think Eric got one thing wrong, though. Pretty sure Bagtime was in the Sun-Times and not the Trib.