Interviews with Interesting People 002: Ken Anselment

College Pricing: An Apocalypse in Not-So-Slow Motion

Ken Anselment is the Vice President for Enrollment & Communications and Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin. Also he’s a good friend and a super smart guy who has spent his career working and thinking about college admissions.

(He is also hilarious. Check out his Lawrence bio page.)

Earlier this year Ken started The Admissions Leadership Podcast, where he interviews people in college admissions and enrollment about the way they do what they do and the state of the field. And even not knowing much about the field, I’ve been inspired listening to college admissions directors thinking of admissions as a mechanism of social change.

I’ve also been kind of horrified. You know how we all talk about college prices getting too high, and this can’t last, and what the heck is going on? Well, it turns out people in enrollment are saying the same things, and seeing that indeed, it can’t last, and more than that that the bottom is pretty much going to drop out in the next five to ten years.

Ken posted an article on Medium about this, which I highly recommend you read before reading on. The title tells it all: “Higher Ed and the Zombie Apocalypse” .

As you see, we jump right in. It’s a great conversation. Enjoy.

Reading that Medium article I felt like I had been invited into this behind closed doors conversation about the future of higher education and discovering it’s this whole other oncoming disaster. I couldn’t believe it’s not on the front page every morning.

The way we price colleges is broken. It’s not financially sustainable. Period. It doesn’t work. Family incomes are flat. College prices keep going up each year, but colleges end up giving more and more financial aid each year so that families can afford to attend. And those that can afford to attend—even those that could pay the whole cost of attendance—often don’t have to because colleges offer them a lot of scholarship money to entice them to enroll. Meanwhile there are so many other families who can’t afford to attend, and many of these receive financial aid awards from the colleges that aren’t large enough to allow students to bridge the gap between what they can pay and what the college costs. It’s out of whack.

Just to be clear, merit scholarships are need blind?

Yes… sort of. (Though “need blind” technically means that a college makes an admission decision without considering someone’s ability to pay.) They’re given without consideration for how much or how little someone can afford to pay—it’s usually used to attract students with things that the college wants or needs, whether that’s academic profile (like high GPAs or test scores) or something more specifically talent-based, like music or athletics. These decisions about scholarship are usually made before the college even knows what a family can afford (which they learn from families filing for financial aid with a FAFSA and any other stuff they require).

Think about it this way. Let’s say you need $20,000 to go to college, and you have already received merit scholarship from the college worth $15,000; that’s technically meeting part of your need, but you’re being given that $15,000 on academic merit. Many colleges will then give you another $5,000 to meet the rest of your financial need.

But let’s say your need is $0; the college may still give you a $15,000 in merit scholarship. You don’t need the $15,000, but you’ll get it anyway. The college is basically saying we’re willing to roll the dice and maybe lose $15,000 a year on you on the hope that you’ll come and pay the rest.

We’ve coached American families to expect not to pay retail, and, as a result, we’ve conditioned many of them to believe that they have to get a scholarship; if you don’t get a scholarship then the school doesn’t really want you. I’ve heard of stories of admissions officers at some schools hand-delivering admission and scholarship awards to some students at their homes, only to have the student whisk past the whole “You’re in!” part to find out how much scholarship they’ve gotten. Sometimes they’re happy with the amount; sometimes they’re visibly disappointed in the amount. The latter makes for an awkward conversation.

So do you think merit awards should mostly go out the window?

That’s the thing I secretly hope for. If I were in Congress I would send a message to all colleges everywhere that if you like getting Department of Education dollars to award Pell grants and subsidized loans, you must discontinue giving merit scholarships and reset your cost of attendance. (Spoiler: I would probably never get elected.)

On the plus side, imagine what a massive college pricing overhaul would do to the economy. Think about what that would do to the massive college loan debt (more than $1.5-trillion) being carried in this country.

What would happen, do you think, if everyone knew what everybody paid to go to college?

I think you would have a really stark illustration of the inequity of the college pricing model. If you have a hypothetical class of 500, and we ranked them according to academic rank (using GPA and standardized test scores) from best to worst, the kids near the top will be paying the least to go to your institution, regardless of family income. Meanwhile the lower end, will quite likely see a disproportionate number of lower-income students. And the students down toward the lower end will usually get smaller financial aid awards that will probably be a disincentive to enroll.

Most colleges don’t have financial aid budgets that allow them to meet 100% of the financial need of every single student they enroll, like a Harvard, Amherst or Georgetown does. Most colleges basically have to array their students on a matrix. In a group of 500 kids, the top 100 kids might get the equivalent of 50% of tuition, the next 100 get 33%, the next 100 get 25% and on and on.

So the more academically qualified you are, the more money many college are going to offer. Because those students help the school’s reputation; they bring higher test scores, higher GPAs. Even those schools who are test optional, they still like good test scores. And why? Professors want to teach “good students”, and their marketing departments want to show a good academic profile to their friends at US News and the other folks that rank schools.

These kids could be a billionaire’s children but they’re still going to get a scholarship at most schools. At Harvard, Yale, no, but people are willing to pay full price to go to Harvard or Yale.

When I was on the board at Marquette University [Ken and I are both alums of Marquette] I remember asking how can we just keep increasing tuition indefinitely. And it was explained to me that the market is so competitive, you have to keep providing the very best of everything – dorms, gyms, dining halls, wifi…

Do they really, though? Or do they do that to justify to that they cost as much as they cost, to charge a higher premium?

Also, since when does college have to be an all-inclusive resort? At the risk of sounding like some old fart, it’s not like McCormick Hall was beautiful; but it didn’t matter. We didn’t care. We didn’t know to expect any better.

[Ed’s Note: McCormick Hall was a 12-story building that once housed 720 freshmen men; it looked like a beer can and also frequently smelled like one. It was definitely not beautiful. But it could be a lot of fun.

Also, it was just knocked down. This is it today:

It seems like a useful metaphor.

What does it say when living in a residence hall on a college campus is the pinnacle of your living experience for the next ten years of your life in terms of quality? Because when you graduate you may not be able to have the same kind of lifestyle as you had in your swanky residence hall with your cathedral ceilings and turn down pillows.

In your article you also talk about the demographic cliff we’re headed towards. What do you mean?

In 2008 when the economy went in the toilet people stopped having babies in the United States. Flash forward 18 years to 2026 and you’ve got a big hole in the 18-year-old population. And it persists; the most recent birth statistics we have, from 2018, the trend persists – so that’s to 2036.

So the number of students that are 18 is going to get smaller. And by the way, they don’t all go to college anyway.

And even as that population is shrinking it’s also becoming more diverse; the Latinx population is for instance growing rapidly but it’s also a lower college-going population.

The situation is dire. I keep having this image of all of us on a highway headed toward a cliff. There are off-ramps, and also some of us are further along [toward the cliff] than others. Because they don’t have a big endowment, they aren’t generating a lot of student revenue or they’re in remote areas in parts of the country where the college-bound population is shrinking rapidly, and they don’t have a national presence. Those are the colleges most in jeopardy.

Lawrence has an international portfolio, so we’ve spread the risk. We recruit heavily in California, and that population is huge and it’s going to continue to be a healthy well for us because the UCs are so hard to get into.

That’s also why we’re in Texas and why we’re in Colorado. But we’re not the only ones.

If I’m a young person of a low family income, don’t my options improve if the overall potential student population is going down? Could that be a silver lining?

You would think so, but no. The better the college, the more selective or high quality-- the more like Yale or Harvard, the fewer the poor kids they enroll. I’d point to Paul Tough’s book The Years That Matter Most: How College Makes Us or Breaks Us to show some of the ways that the wealthiest colleges seem to be doing the least when it comes to enrolling and educating the neediest students.

That’s the other thing that doesn’t makes sense about our model: the poorest colleges are generally educating the poorest kids. That is, the colleges with the fewest resources are doing the educating of those most in need. Meanwhile Harvard is educating extremely wealthy people and just a fraction of poor people. They could do so much more, they could afford to do so much more. But they don’t have to because they’re Harvard.

You said at the start you dream of being able to get rid of merit awards.

I want to hear what economists have to say about the idea. Maybe I’m wrong. But yes, I wonder if we got rid of merit scholarships, if every college did it, and adjusted the price down what the impact would be.

Explain to me the “adjusting the price down” piece.

Let’s say my tuition cost is $50,000 but I have to give away on average $25000 to get students to come here. Shouldn’t I just be charging $25000 or maybe $30000?

That means I wouldn’t be able to collect as much from wealthier families, but poorer families would be able to access education more easily because they would have less far to stretch to pay. And they might be able to get some need-based grant and take out some loans and make it work.

One other thing you were telling me about offline is this recent Department of Justice decision saying colleges had to change their practices to basically allow poaching?

So… as if the combined challenges of counterproductive college pricing and shrinking college-going populations isn’t enough to keep enrollment people up at night, we have a new wrinkle that entered the system in September. The Department of Justice—yep, that DOJ—had been investigating the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), an organization that exists to ensure that students are protected as much as they can be at a critical and vulnerable time in their lives. The DOJ’s problem? They took issue with three items in our Code of Ethics and Professional Practices (CEPP), saying that each was trade-restraining, preventing colleges from conducting business and, at the same time, preventing students from getting the best financial aid they could get.

For example: one of our professional code statements tells colleges that once a student declines your offer of admission, you need to stop recruiting that students. Don’t come back to them with more financial aid to sweeten the pot to try to “poach” them. Just sing your favorite song from the Frozen soundtrack and, you know, let it go.

The DOJ threatened NACAC with heavy-duty litigation. When we last looked, the government has more money and more time than a volunteer organization of 15,000 college admission officers and high school or independent counselors. So NACAC members, in an act of institutional preservation, voted to eliminate from the CEPP the three clauses that the DOJ took issue with.

What that means now is that colleges can, if they wish, keep recruiting students after they have said no to them. They can do so all summer before the students enroll at their chosen college. They can even continue to do after the students enroll at the college. Yep. College can recruit students from other colleges now. Will they do it? I doubt most will. But now that they can, it means that there is the potential for an industry-shifting behavior. Fun times.

It has the potential to erode financial aid budgets at colleges, and at colleges that are already in financial jeopardy, this could hasten their demise. A lot of folks in this profession are unmoored by this.

Last Question: What’s your favorite and least favorite pop culture apocalypses?

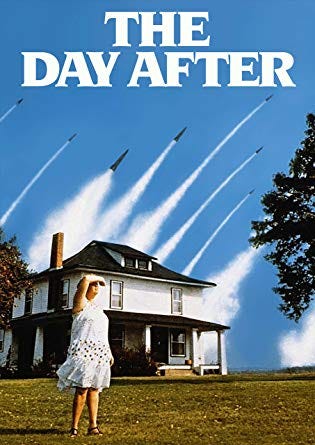

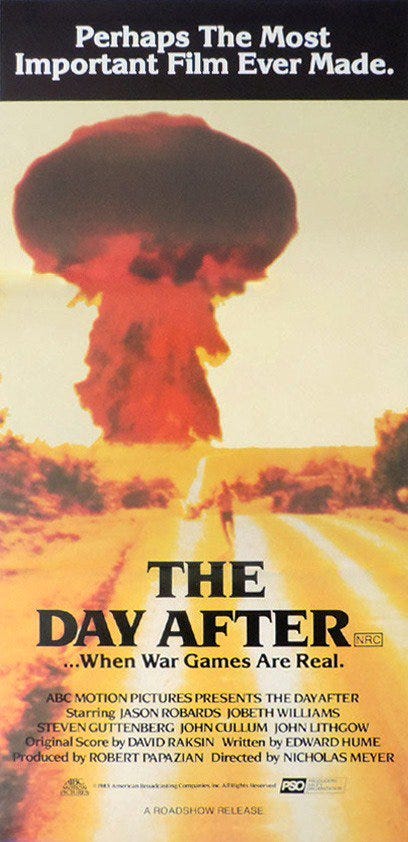

Give me a nuclear event and I’m yours. I was born in the 1970s, which means I was at prime freak-out age when The Day After aired in 1983. I remember helpful and terrifying NBC prime-time news stories about what a nuclear winter would be like. (Because puberty wasn’t scary enough!) Nonetheless, big mushroom clouds silently flashing in the distance over Lawrence, Kansas (or LA just 8 years later in Terminator 2) transfixed me.

Man, The Day After really messed with my head, too. One of my strongest memories of childhood is being afraid of nuclear war. I can’t imagine why…

And your least favorite?

Maybe my least favorite apocalypse scenario are the ones where you don’t know what caused the apocalypse in the first place. I loved reading The Stand when I was a kid, because there’s nothing so fun as a worldwide cholera outbreak to bring on the end times. On the other hand, The Road, which is perhaps the bleakest thing I have ever read, never spills the beans on the cause of the nightmare scenario, instead letting you marinate in the supreme awfulness of life after.

Ladies and Gentlemen, a round of applause for Ken Anselment!

Thanks so much, Ken. And thanks to all of you for reading. You can find Ken on Twitter at @kenanselment.

I’ll have the normal Wow up on Sunday. Have a great weekend.