POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

I spent most of the last five years exhausted by the constant Hamilton hot takes. It was like the internets had said, Girls has ended, WE ARE HUNGRY MORTALS. And this was what we got.

But five years later when I heard Hamilton was coming out on Disney+ this weekend, I was IN for all of it. Because it’s still 2020 y’all. To get through this we need everything we can put our hands on.

Not everyone felt the way I did. Take my mother. Here’s her hot take on the show.

Later I found out she has yet to watch Act Two. She told me this in the comments of my Facebook Mass this morning.

As soon as the Mass was over I CAPS-shouted at her to watch Act Two immediately. Which is the online Mass version of publicly condemning someone a sinner.

Please pray for us at this difficult time.

I’ve got a bunch of hot takes of my own about different moments in the show. For those of you who have already read and watched everything about Hamilton, I’m assuming most of them are familiar and I’m like the guy who just discovered Lost and is like, WHO WAS THAT IN THE CANOE?

But I am going to tell you them anyway because Hamilton is English major catnip and Hi My Name is Jim and I am interpretation addict.

Here’s a question for you: Whose story is this? It’s called Hamilton, so it should be pretty obvious, right? Except from the very beginning Burr stands forward as the narrator of the story. And even after Alexander is introduced, we return to others narrating his life story.

There’s actually a very Sweeney Todd vibe to the opening of Hamilton. In both, the main characters and chorus of the play introduce the main character to us in song, telling us his backstory, after which he shows up. These narrative vignettes also keep coming back in Todd, just like they do in Hamilton. And the story ends after Todd has died, with the other characters singing about him, just like in Hamilton.

I started making those connections this afternoon, then I found this:

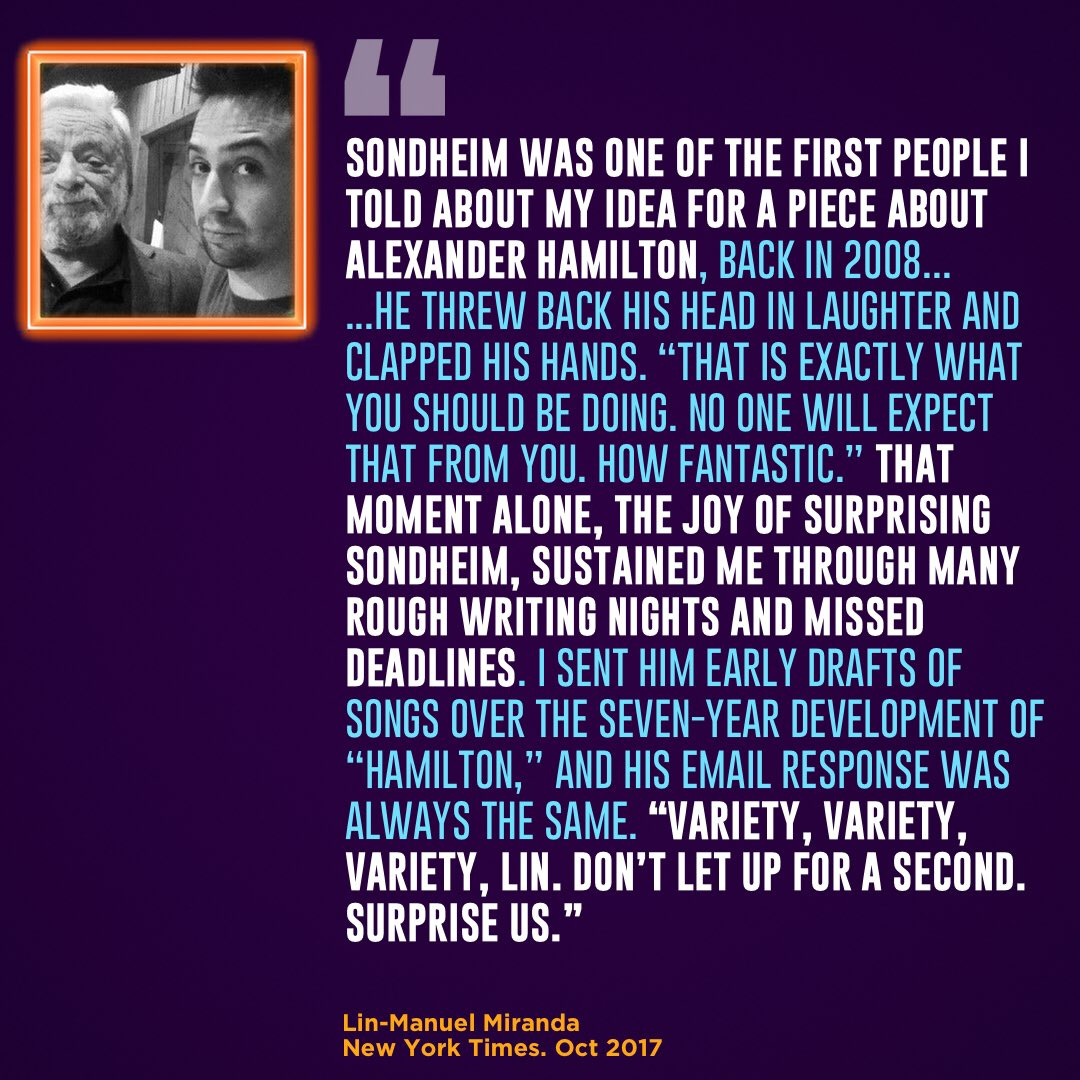

Miranda really loves Sondheim.

In fact:

In another way, though, you could argue this ends up being Eliza’s story, not Alexander’s. When they get married she tells him “Let me be part of the narrative.” Then he basically doesn’t; until his son dies his family is mostly just an appendage on his work. When she finds out he cheated on her she burns all his letters and says she’s writing herself out of the narrative.

But at the very end, after they’ve reconciled and Alexander has died, we find out it’s Eliza who kept Alexander’s legacy alive. She actually went out and interviewed the troops he had served with, told their stories. She tried to organize his 1000s of pages of letters Alexander had written. And she did a hundred other things that allow us today to know who he was.

Point being, there is no Hamilton: An American Musical without her work. She had it all wrong when she asked him to let her be part of the narrative. It’s because of her that he’s a part of our narrative. And not just him – she fights against slavery, raises money for the Washington Monument (George standing behind her sings “She tells my story”) and starts that orphanage –

(Me EVERY TIME I get to that part of the last song:

SHE STARTED AN ORPHANAGE YOU GUYS.)

At that last moment, she asks whether she did enough, “Will they tell my story” – and Alexander steps forward, takes Eliza by the hand, brings her to center stage and then steps back. And there’s something in the way Miranda performs in that moment; he has none of the seriousness or intensity of Alexander, instead he smiles with all the kindness that anyone who has ever seen Miranda on a talk show is very familiar with.

It’s like rather than Alexander, Miranda himself is giving Eliza this chance to see what all her work created.

And Eliza looks up and around at the audience and gasps with emotion. And that’s how the show ends.

(Yes Mom, you really should watch Act Two.)

There’s some really interesting stuff that goes on in Hamilton between theme and what I’d call a choreography of stillness. When King George comes out to deliver his main song, “You’ll Be Back”, he is almost entirely stationary while he’s singing. I want to say the only thing that’s moving most of the time is his face, but even that is not accurate; usually it’s just his mouth and eyes. When his head moves it’s only slightly and slowly, other than a couple big moments.

It’s very unusual, like he’s a statue. And in fact he looks very much like a statue – other than his face he’s completely covered by his royal getup.

All of that goes right to theme. He’s presenting himself here not as a person or a point of view, but as ENGLAND. That is, a fixed part of reality, something beyond time’s woes. “Oceans rise, empires fall,” he sings, which on the face of it sounds like Yeats. Everything collapses in the end. But he ends the verse this way instead: “We have seen each other through it all.” England survives even beyond the oceans and the empires.

(Meanwhile, when describing the claims of America he repeatedly begins “You say”, indicating their relativity and arbitrariness. It’s not the truth, it’s just what these bumpkins say.)

The last time through the chorus he holds “ever” an unnecessarily long time – again, speaking to permanence – then slides directly into the last verse without a breath, change in facial expression or even movement in his eyes. He is granite. Try fighting that.

The other fascinating thing about his choreography: when George does move forward on the stage, he steps slowly and always placing the forward leg across the back leg. It’s a classically feminine style of walk. The fact he’s wearing hose only emphasizes that sense.

I’m intrigued as to that choice; it almost seems intended to make him seem unconsciously silly. But he’s so powerful and self-contained as a figure, I tend to think instead it’s meant to indicate just how far above you and me he is. No rules apply to him. If he wishes he can walk like a fancy lady – seriously, watch him move, he is FANCY. And not only will no one question it, no one could. He is England. He can be as fancy as he wants to be.

A very strange moment at the end of this scene: as George leaves the camera turns to a woman who we don’t know, receiving a letter from another. And then, while George is still on stage, she’s killed by a redcoat. George watches it happen, makes a gesture as if to say, “This is what you’re in for” and leaves.

That woman is part of the ensemble. And it turns out she keeps coming back throughout the show in a very specific way. In fact, she’s pretty much the harbinger of death.

Supposedly every background character in Hamilton actually has a full storyline of their own. That’s how layered the show is. INSANE.

A different kind of stillness happens in the song “Satisfied”. We’ve just witnessed the whirlwind love story of Alexander and Eliza, we’re at the wedding reception and older sister Angelica raises a glass for the toast.

And as she begins her toast the scene rewinds around Angelica back through the wedding and the whirlwind romance, to a small moment that happened only in passing, Alexander meeting Angelica for the first time and kissing her hand.

It turns out running parallel to what we’ve watched has been her own story of falling in love with Alexander and giving that up for her sister.

The choreography of the rewind is unbelievable. It captures so many small details of movement from the prior scene. And as it’s all happening, and then again as time restarts with the full details of her meeting with Alexander, Angelica simply stands there in the center of the stage, trapped – exactly like Burr – in a cone of light.

(When Alexander kisses her hand, the chorus standing – still of course -- all around the edges all give a gasp. It’s such a nice detail.)

Then the scene moves on through the wedding reception, and as she sings to us still she’s stationary, even once her sisters take her hands and wind around her. Take a look at the image that creates:

She’s literally tied in place by the arms of her family.

Slowly she gets drawn in, as an object of other people’s movement—Washington’s, her sister’s – and then the chain of events we’ve already seen. She walks Alexander to Eliza again, as she’s talking to us. Then she starts explaining why she’s done that, to be interrupted only by her next “line” in the “play” she’s already witnessed with us. And it goes on and on like this—even as she’s talking to us, she’s trapped in events that have already happened, right down to the choreography she has to do. (Check out the moment when she takes the letters from Eliza and Peggy; as she backs up with them it’s like she’s being literally pulled along.)

And then she’s back to her position in the very center, stationery as Alexander and Eliza come up and down stage on either side of her. And suddenly we’re back at the toast, people whirling around and getting back into place while she is leading them in the beginning of this number. “A toast to the Groom! To the Groom!...” She’s fully locked back into the play, but now everything she says means something else to us.

(My favorite moment in all this is watching someone whirl by and placing a glass back in her hand, just in time for her to raise it.)

In a way she’s become us in the play, aware of it as s play and with definite feelings about it all.

The scene ends with her still standing there, perfectly still, raising her glass and now all alone. The story has moved on without her. And her line: “I’ll never be satisfied.”

The podcast Strong Songs did a whole episode looking at the music of “Hopeless” (Eliza’s whirlwind love song) and “Satisfied”. It’s so worth listening to.

Eliza, Alexander and Angelica each have their own musical motif that plays whenever their name is sung. And those motifs end up being expanded in “Hopeless” and “Satisfied” in insanely crazy ways.

Listen to it here.

One other key thing from that song: Alexander is not interested in either one of the for themselves. He needs their name. There’s a fabulous moment in the song where he stands between the two of them, a group of men directly behind him, all kind of cardboard cut outs of each other. And he looks to Angelica, as do they. Then she points him toward Eliza, they turn him that way and that’s that.

And again at the very end, having just married Eliza, as he leaves the room his eyes follow Angelica. We don’t see his face, just his head, but it’s just wrong.

One of my biggest surprises after watching the film, actually, is how little I like Alexander. He not great, you guys.

The comedian Katherine Ryan has gone deep on the many problems with Alexander and I am here for all of them.

A third example of stillness: Aaron Burr during his big number “Wait for It”. Until the very end, any time he does move it’s in a tightly circumscribed circle. Usually his movement amounts to just shifting direction.

As with the other two, there’s a great power in his stillness. The less he moves, the more our attention is locked on him. (They even seat cast members in the corners around him, their own unmoving gaze also pointing us to him.)

And once again that stillness also speaks to theme. On the one hand he is not moving because he is waiting for his moment. In large part the song explains why he’s like that – and it’s all about death (which is fascinating in its own right: just before his own death Hamilton will reveal he too has been consumed his whole life thinking about his oncoming death. Burr has spent the whole play wondering why his fellow orphan Hamilton writes like he’s running out of time; it turns out it’s for the very same reason that he lives lying in wait…because death doesn’t discriminate between the sinners and the saints, it takes and it takes and it takes.).

On the other hand, that tightly circumscribed circle he moves in – which is captured even in the lightning that pours down on him -- tells us how trapped Burr is. He has all this power and yet he’s in a prison.

Hamilton himself gets his own kind of motion-stop moment as the bullet that’s going to kill him is flying his way. But he gets to move around a bit more; that’s actually part of the brilliance of it. Unlike the others he gets to move, but it doesn’t matter where on stage he is, the bullet is still coming for him.

(My favorite moment: the scene ends with he and Eliza facing each other, hands extended. He tells her not to hurry to meet him. And as she turns away, the shape of her hand shifts from open extension through the shape of the coming bullet.)

The other thing about that moment – Alexander doesn’t sing. Spitting verse has been his super power; it’s all gone now.

And we’re back to the end of the musical and Eliza.

One more tremendous part about that moment: even as Hamilton has this tremendous diversity in its cast, capturing both the truth of Hamilton, a Scottish/French immigrant from the West Indies, and also the gorgeous truth of our country, it’s still fundamentally the story of a bunch of guys saving/creating/whatever the United States. And that’s a narrative that forgets a lot of other people.

At the end of his bold retelling of our history, by raising up Eliza as the one responsible for these truths and figures of our history, Miranda upends not only American history as we teach it but in a sense what he’s done here too. The stories we know, the histories we seize upon in Twitter battles and rallies and Thanksgiving dinners come from people we forgot. The real history of America is then and now being carried by groups we ignore or dismiss.

So there you go. Hamilton, the Pulitzer-Prize winning musical that made my mom shrug. I recommend it.

The Hamilton cast was on Fallon last week, performing “Helpless” from home. It’s delightful.

And for those who are NOT into musicals, thank you, how did I start getting this damn newsletter in the first place, let me try and ease your frustration with Ryan Reynolds…

…a beautiful thread about the great Carl Reiner…

…and the sound of foxes laughing.

Life doesn't discriminate

Between the sinners and the saints

It takes and it takes and it takes.

And we keep living anyway

We rise and we fall and we break

And we make our mistakes.

And if there's a reason I'm still alive

When so many have died then I’m willing to wait for it (wait for it) (wait for it)

Right here with you. See you next week.