EPISODE 308: PLAY IT OFF, KC

POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

Keyboard Cat is dead. Robin “Mork” Williams used to do horrible things to Pam “Mindy” Dawber (but she doesn’t mind). And in addition to cyberstalking you themselves Facebook has been selling your information to other companies, which is the same as what we knew before but now it’s about the election and so outrage.

Oh, and Stephen Hawking died and it kind of seemed like no one really knew what to say. For me, the Economist came closest:

...Once he could no longer write down equations, theories had to be translated into geometry in his head; and after a tracheotomy in 1985, the ocean of his thinking had to be forced through a cumbersome and narrow technological aperture. His words necessarily became so few that he had to stare hard at the universe in order to define, and refine as far as possible, the new things he had to say about it. His theories of everything emerged in a voice that was both robotic, and curiously laden with emotion.

++

Imagine working at Facebook right now. No way that’s the Silicon Valley Fun Time Band you signed up for.

By most accounts it never was, either. Mark Zuckerberg is no Steve Jobs. There’s always been that something in his eyes, a strange absence, like the person in front of us is just a flesh sleeve Zuckerberg operates when he has to engage with people. He’s just never seemed altogether there.

His company has been much the same. Google was the company that made “Don’t be Evil” part of its motto—notably, it has since dropped that in favor of “Do the Right Thing”, while helping create AI systems for military drone strike targeting systems.

But Facebook and Instagram (which it bought) have also packaged themselves in the same gauzy aura of niceness and hugs. Twitter is for trolls; Facebook is for family.

In fact Facebook makes its money deciding which friends you see, selling everything you post and watching everywhere else you go. I can’t even read what some of my friends and family post if I don’t create a special group or use Facebook’s “Best Friends” category, both of which then become further information that Facebook will both use and sell.

We think of Facebook as like the town square where you can find everything, but really it’s more like a mall, privately owned, with cameras everywhere. Except malls aren’t allowed to sell their surveillance data or to follow you home.

Can anything change there? I don’t know. I’d like to see them drop their newsfeed algorithm and just let me see what my friends post. And obviously I’d love for them to stop watching everything we do to such a degree that they’re so able to predict our wants many many people think they are listening in on us.

(Dear Facebook, it’s only okay to watch us as long as we’re not made aware that you’re watching. You've pretty much discovered the social media version of the uncanny valley.)

From what Zuckerberg said Wednesday it’s not clear to me that he really sees just how deep the company’s problems are. This is not just a series of regrettable mistakes. Neil Patrick Harris is not going to be able to put on a rubber nose and liver spots and come save you. You can’t fix what’s going on with “Gosh darn it, we’re gonna try so much harder”.

Or as my favorite moral theology teacher used to tell us, the sin you need to worry about is not the one you're always confessing, but the one you refuse to see.

++

Having said all that, last week I also read this great piece on How to Hack Facebook’s Algorithm and Drive your Friends Insane. Basically, with Facebook’s new emphasis on more “personal” interactions, if you post stuff that elicits a lot of comments, it will stay on your friends’ newsfeeds for days and days, even if people are only responding because your post is terrible and they hate it so much.

Challenge Accepted.

++

Last week America published an article I had been working on for the last six months about the four California/Oregon family farms responsible for pretty much all of the Easter lilies sold in North America (a little over ten million bulbs per year).

In September I had spent ten days at the northern border of California reporting on these farms. And I went there thinking my piece would be an easy sell with the farmers; Catholic priest, writing for a prominent publication whose readers are right in the sweet spot of your market? What more could you want?

But in fact what I met was a unified front of rage and distrust. The only farmer who got back to me before my visit told me not to come onto his property. When I arrived in Smith River representatives from the four farms insisted we meet as a group. Then over the course of about two hours, they told me story after story of sympathetic journalists coming up saying they were just interested in learning about this unique and challenging business and then turning out pieces informed instead mostly by the accusations of a local environmental group which for over a decade has been accusing the farms of poisoning the locals, the river and the land.

Here’s the thing: I had read all of those stories and talked to that environmental group. And the idea that the flowers that Christians rely on to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ were actually killing people absolutely was the thing that had first turned my head and gotten me interested in the bigger potential of the story. It was a Catholic Silent Spring; call me Aaron Brockovitch and hand me my Catholic Press Award, please.

(Fun fact: I have no idea what a CPA award looks like, but in my imagination it is remarkably similar to an Emmy. And it’s a lot heavier than you’d think.)

Sitting there listening to those farmers, hearing not only their frustrations but the depth of pain caused by a decade-long war of attrition with this environmental group was a revelation both about them and about me. I had come here to get their side of the story, yes, but I had also already without talking to them decided what the story was, and in no small part because of what I saw in it for me.

++

I don’t think of myself as a journalist, any more than I think of myself as a screenwriter. I just don’t think I’ve earned it. I’m happy to be able to call myself a writer; the rest is like wearing your dad’s clothes to school.

Having said that, working for America these last few years has definitely gotten me in touch with some of the uncomfortable ambiguities of journalism. On the one hand, I fall in love with pretty much every person I interview in any depth. It is very hard to be objective about someone once you’ve gotten to see what they’re dealing with.

On the other hand, a lot of the time the job of the journalist is to convince other people to reveal their lives (and pain), at least in part for your benefit.

That’s not inherently a bad thing. Sometimes you have a Big Story that Needs to be Told.™ Maybe you’re helping lift up voices and stories that are being ignored.

But man it can get complicated. Last week I went to the Student Walkout on the LMU campus where I live. I went because I am deeply troubled by the issue of guns in our country and I am struggling to figure out how I can help, if at all.

(So far “Pray for a change of hearts every day” is about the only thing I’ve come up with that seems like it might possibly have any impact. As a priest maybe I should be satisfied with that?

I am not.)

But as I walked over I scanned through Twitter and saw some journalists I like posting photos of young people at other protests alongside brief punchy comments about who they are and what they want. “Ooh,” I thought, “Great idea.”

And based on the strange cheerfulness that some of our students showed, probably they would not have minded getting their picture taken while they adopted a momentary solemnity. #WalkoutSelfie

(I don’t entirely mean that as a judgment. What are we fighting for, if not a world where every child can be so insulated it’s impossible for them to imagine someone showing up and gunning everyone down?

But in the moment it was pretty jarring--like going to a crime scene and overhearing someone talking about how they can’t wait to get a pumpkin frappe.)

But a lot of other people were there with feelings and experiences that were deeply personal. For me to ask to be able to open up to me so that I could post it on social media (of all the dumb things) seemed fundamentally wrong. Disrespectful, intrusive and an act of commodification. Your life is a commodity for me to sell.

++

If every reporter and news photographer always felt that way, many important stories wouldn’t get covered. And we as human beings would lose a key means to challenging our own assumptions and expanding our sense of understanding.

But I also remember the days following the car accident that would eventually claim my sister’s life, getting home from the hospital to watch my parents listen to message after message from TV reporters who wanted an interview. And each reporter adopted the same “feel for you” tone while talking a mile a minute and clearly not seeing that there was an actual tragedy going on here, that one family was about to lose their thirteen year old daughter while two other families’ daughters already had, and also that this wasn’t really news, just an opportunity to drive by the scene of an accident and see if you get a glimpse of any blood.

I feel pretty sure most writers we know and love have had more than their share of using people, either because they’ve had a deadline or an opportunity or a point of view you refuse to evaluate. It’s an unavoidable hazard of the job.

But I’m starting to think for me the work of writing has to involve putting myself in positions where I can’t avoid seeing my own assumptions (and general human monster-ness) and being forced to act otherwise. Interviewing people I don’t understand or maybe even don’t want to like. Being forced to accept they’re human beings, too.

At the end of their two hour litany of frustration, I was shocked to find most of the Easter lily farmers willing to talk to me anyway. It wasn’t because I was a priest. (In fact, they told me the fact I was a priest writing for a major Catholic publication gave them enormous pause. If I trashed their business, what consequences might it have for their sales?)

No, it was more like they agreed because that’s just what you do when someone comes to visit. You’re hospitable, whether it might hurt you or not.

Imagine that for a second. After reams of stories that ignored the reality of their lives (and after talking to the state, the county and the regional authorities I feel pretty safe in saying those attacks were phenomenally unfair), they still couldn’t help but treat me as a person.

I’ll always be grateful to them for that, and for demanding that I pull my head up and see them. I’m not sure what readers will make of the piece; we seem to be marketing it as a warmish feature about lilies, when it’s actually about the struggle for these farms to survive, and the love of the craft that keeps them going anyway. For me it’s a story about having faith in small town America, and in the attempt at least it’s probably the article I’m most proud of.

++

Last weekend was the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Religious Education Congress – forty thousand Catholics hanging out, hearing great talks and buying stuff. Basically it’s Comic-Con with different costumes.

I got the chance to hear Father Greg Boyle, S.J. talk about his new book, Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship. (He's a great writer. Highly recommend.)

Greg has spent thirty years working with former gang members, helping them to find both emotional/spiritual help and steady employment. He’s a Congress rock star, always gets huge crowds to hear his funny stories about the “homies” and the serious insights they have given him into life and faith.

In the middle of the talk I heard, which had the great title “Ventilating the World with Tenderness,” he went into an amazing riff on tenderness and demonization. I didn’t get down every word of it, but I got a lot.

Be untidy in your exuberance.

Tenderness is spirituality at its most mature. Our goal is to become God’s tender glance in the world.

Winning the argument does not ‘get us there’. It only keeps us from arriving.

Find me a place in the Gospel where Jesus is defensive.

The opposite of God is demonizing. It is the opposite of how God sees things. God does not share in our demonizing of Donald Trump or MS 13. God does not share in our demonizing of doctors who perform abortions or agents of ISIS. God will not have any of it.

Believing in demons is the gateway drug to demonizing.

Demonizing is all the rage these days; in fact it is the container of our rage. Demonizing is where our rage goes to when no one else will let it sleep on the couch.

When we demonize we’re not even trying. It’s just plain laziness.

God is able to get underneath stuff.

Today the measure of our moral compass seems to be how outraged we are. But moral outrage is the opposite of morality.

Demonizing keeps us from solutions. When we get underneath stuff, we see the same thing God sees: wound, trauma, damage, mental illness.

If it’s about morality, there is no hope. But if it’s about healing, then everything can change.

If you’re a friend to your wounds, you won’t be so tempted to despite the wounded.

It is impossible for people to despise people that they know. It is impossible for humans to sustain that.

God does not have enemies. Only children.

We are not invited to have enemies, either. Only sisters and brothers.

++ LINKS ++

Marvel: "Infinity War is the most ambitious crossover event in history.” Me:

I'm not ashamed to say this joke is my proudest moment.

I promised to stay away from games and gamification this week. But I came across this interesting piece about a new plug-in that hides the number of likes and retweets for posts on Twitter or Facebook.

.

I’ve been using the Twitter plug-in for the last week. It’s strange in that you no longer have a sense of the broader engagement of some tweets. But it means each post kind of stands on its own, too.

From the article:

After three weeks of using the Demetricator, the nature of Twitter, for me, changed completely. In some ways, it became lonelier. Part of the fun had been feeling like part of a crowd, seeing a joke or an idea or an observation become something that fifty people, or fifty thousand, could share. But I’m willing to accept the loss of this superficial sense of community for all the gains. Not seeing any numbers at all made content itself the king. I came to appreciate, disconcertingly, that knowing what was popular before had not only often distorted but also sometimes completely overtaken my experience. With the numbers gone, I realized that they, indeed, had forced a sort of automated experience, guiding and constraining my behavior.

In other news, the New York Times has started to post obituaries for women that it had previously overlooked. They include people like writer Ida P. Wells, poet Sylvia Plath and Emily Warren Roebling, who oversaw construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. (How did these women not get a write up in the Times already? It's astonishing.)

And lastly, the story of a childhood that ended up somewhere between a spy novel and a fever dream.

“What is Keyboard Cat if not the personification of death?,” writes Jeremy Gordon in his brief eulogy for the one-time YouTube icon. “And what is death if not a lethargic kitty ready to score your exit from the stage? It seemed very meaningful then, as an intensely stoned college student; it seems a little meaningful now, as I ponder how the legacy of this dopey cat, who almost certainly never knew what was going on as it happened to him, but nonetheless gave us a lot to think about.”

Right about now it kind of feels like we’re all in that same boat, pushed and pulled and made to bang on stuff for somebody else’s entertainment without ever really knowing what is going on. But Keyboard Cat had power, too. Him "playing you off" was the noughties' version of a sick burn.

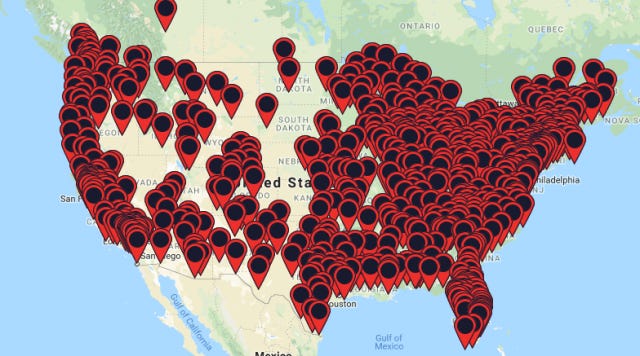

This Saturday is the March for Our Lives. According to the event’s website there are 838 different marches going on – and not just in the United States (which when I stop to think about it kind of gets me choked up; people all over the world are trying to help us, guys).

If you go to that website you will almost certainly find a march close to you.

The Eastern half of the United States is basically one big march.

Love it.

Maybe we are just Keyboard Cat. But I'm hoping that also means there's something we can do.

Here we go.