EPISODE 231: DEFENDERS

POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

Last week at this time Netflix dropped The Defenders, its superhero team-up show starring the leads of its four other Marvel shows – Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage and Iron Fist. Basically, they’re the Street-Level Avengers.There is a big bad that’s pretty darn big and pretty super bad, but there’s no magic hammers here, no suits of armor or men who turn into monsters sporting surprisingly elastic surprisingly purple pants. Our cast is a former cop trying to save a mother's last surviving child; an alcoholic detective trying to explain a man’s suicide to his grieving widow; a blind defense attorney trying to rescue someone he loves; and a martial artist who is rich and also like a cosmic Jesus and okay I admit it now he’s getting kind of annoying.

Point is, these guys are like you and me. They ride in elevators and go to dive bars and take the subway. They have to deal with police and making rent and hangovers. You could meet them on the street and hire them to do stuff for you. Which – and this is hard to believe given the absolute glut of superhero stories out there – is actually a pretty original take, and also makes for some of Defenders’ most satisfying moments.

Like many of the things you’ve even seen from Marvel, this team is really the brainchild of one guy. This guy:

His name is Brian Michael Bendis, and yes, he does fancy a jaunty eyebrow wiggle.

BMB, as he’s called online, has been writing comics for a couple decades now, and he’s been intimately involved with many of 21st century Marvel Comics’ riskiest choices. As a young writer he was put in charge of an alternate universe Spider-Man origin story reboot called “Ultimate Spider-Man”, which no one expected to work, because comic book resets of characters never do and also he was a comic book crime writer with not a lot of credits. And it became this huge hit that’s still going sixteen years later and clearly inspired a lot of the best stuff in Spider-Man: Homecoming. (Peter's friend Ned is a direct rip-off of a character Bendis created.)

Then Marvel put Bendis on Daredevil with artist Alex Maleev. It, too, did really well. A couple years later he created the character of semi-alcoholic deeply-scarred detective Jessica Jones with artist Michael Gaydos. That series (called Alias) also occasionally featured Luke Cage as Jessica’s on-again, off-again boyfriend. Which was kind of crazy; no one had seen or successfully used Cage – a 1970s blaxpoitation ex-convict superhero who went by the name of Power Man -- in decades.

Maybe it was the boots.

Bendis and artist Gaydos portrayed him as emotionally strong, deeply moral and capable of saying everything in a single look, and it absolutely worked.

In 2004 Marvel put Bendis in charge of The Avengers. He promptly destroyed, drove crazy and/or emotionally devastated everyone on the team and replaced them with a combination of a few of the usual suspects -- Captain America, Iron Man -- and a bunch of street level characters who had never been Avengers – Luke Cage, Wolverine, Spider-Man and Spider-Woman (who is part spy, part detective, and almost certainly bound eventually either for a season of Jessica Jones or her own show).

Long time readers went crazy – as they have on pretty much every Bendis project -- but it was a huge hit.

(And yes, while it seems like a no-brainer today, it’s really true, before BMB Spider-Man had never been an Avenger. It was actually a company rule, a sort of “All our kids are to stay in their own lane.”)

Over the course of his run Bendis kept upping the street-level quotient, eventually bringing on Iron Fist, Jessica Jones, Mockingbird (another fighter) and the Thing. Luke eventually becomes the leader of the Avengers. His goal for the team: to help normal people.

Sound familiar?

++

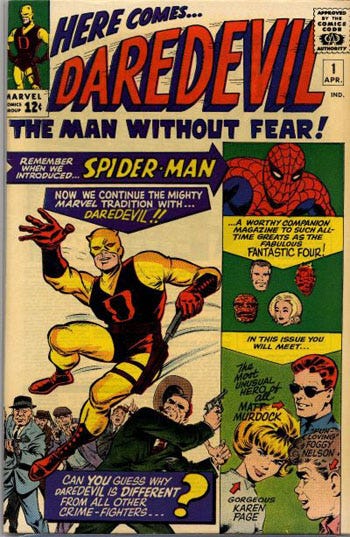

Daredevil has been around since 1964. He’s the creation of Stan Lee and artist Bill Everett, with input as well from comic book giant Jack Kirby.

(You have to love these early covers. They're an absolute mess visually, but they sell the heck out of their characters.)

For those who don’t know his story: Matt Murdock was an ordinary Catholic kid living in Hell’s Kitchen with his single dad, a professional boxer. Seeing a man about to be hit by an oncoming truck, young Matt rushed to throw him out of the way but in the process was doused in some sort of radioactive substance the truck was carrying. The chemicals blind Matt but heighten his other senses and give him a sort of internal radar through which he is able to “see”.

As an adult Matt becomes a New York defense attorney working with his buddy Foggy Nelson, and at night dresses like the devil and fights crime in the Hell’s Kitchen.

When people think Daredevil, generally they think blind, lawyer and Catholic. But I think what stands out for me in recent comic interpretations of the character is his willingness to leap. Matt Murdock is unafraid to throw himself off a building without knowing for sure what’s on the other side or how he’s going to land. He's often depicted spinning through the air in crazily acrobatic ways with total abandon.

A couple favorite images from recent issues:

Matt also reveals his secret identity at times that other super heroes would not. Often he ends up regretting those choices. In the world of Matt Murdock, people get hurt. Loved ones die. He struggles with a lot of guilt and grief. (Did I mention that he's Catholic?)

But no matter how dark things get for him, underneath it all he maintains an abiding trust that the universe has some kind of a net. That things will work out, even if you don’t know how. And that life offers opportunities for great joy if you’ll let it.

++

And speaking of opportunities for great joy...

...Justin Glyn, S.J. is a South African by birth, a New Zealander by citizenship and a priest in the Australian province of the Jesuits. A lawyer with a PhD in administrative and international law, he’s now studying canon law in Canada. And when he’s not busy with all of that (!), he writes excellent, thoughtful pieces on things like Kim Jong Un, Syrian chemical attacks and whether recent U.S. attempts to ban Muslims don’t have their origins in the policies of the Obama administration policies.

After my comments on Wonder Woman Justin had this to say: “I suspect that - rather than tracking genres - when the Superhero movies are at their best, they defy genres and get people to look again at what constitutes weakness and strength.“

He also noted the problems of how pop culture usually presents disability. Justin is legally blind himself; given the fact that he’s also a lawyer, Daredevil comments come pretty frequent.

I reached out to Justin after his note to ask if he’d be open to an interview about pop culture and disability. And not only did he give me that, but he was willing to answer a bunch of questions about his own experience with disability. I can’t thank you enough, Justin.

Hi Justin. Let me start by asking some questions about your own experience with disability. Have you been blind all your life?

Thanks, Jim. Yes, I have. My disability arises from a brain, rather than an eye, issue. Brain tissue seems to have grown in the wrong spot causing damage to the optic nerve. While, like most blind people, I have some residual vision, the world is a fuzzy blur as my eyes cannot focus or work in tandem.

How would you describe what it's like to be blind, and to interact in a world where most everyone else is not?

The first part is a surprisingly hard question. This has been my world since I was born and so the world has always been a fuzzy blur. That’s life.

The second bit is a little easier. There are plenty of things I can’t do - and this is the image most people have of blindness - jobs as a photographer or a pilot are clearly out!

That said, there is an amazing amount of possibility. I think I am alive to things that others aren’t. No, it’s not Daredevil or something with super senses but rather that I rely on skills and coping strategies that others don’t use because they don’t need them.

Can you say more about that?

I have learned to rely a lot on my hearing and memory - which then has spin offs in other areas. So, developing my memory to find my way around or retain what I have learned has made me very good at learning languages and at the research and information retention which you need to practise law well.

A good ear helps with singing - but can be dangerous! A classic (and hilarious) example of where my hearing gave me an edge was a night time meal at a restaurant sitting outside with a whole bunch of other scholastics. Suddenly, I heard something hit the ground and reached for it - a credit card dropped by people getting up from the neighbouring table. Neither the group leaving nor the other schols had any idea what had just happened or why the blind guy was suddenly rushing at the folk from the next table. After fleeing in apparent terror from the lumbering idiot running towards her, the friend of the young lady who had dropped the card realised that I hadn’t completely lost the plot and was trying to help. She persuaded her friend to stop long enough to get the card back. As you know, Jesuits love stories and that one became a staple of the Melbourne theologate!

You’ve lived in a lot of different countries. Have you found disability treated or imagined differently in different places? When it comes to sight-related issues, what have been some of the best practices you’ve experienced (or the worst, for that matter)?

That’s hard to say, and there’s a lot of variation within countries. I think Auckland (NZ) and Melbourne (Oz) have been pretty good - both for accessibility of the environment (traffic signals with audio, ridged pavements and general assistance) and for general treatment. For accessibility on public transport, Melbourne and Moscow are tops in my book, with Singapore not very far behind. You can get anywhere and there is audio on all forms of transport (which is cheap or free for blind people). Best practice has been when people have treated me like anyone else, perhaps asking if there is something obviously visual which I might miss or where I might need a hand but otherwise playing it cool.

Some of my worst experiences have been in Sydney - I have been spat at, insulted (random shouts of “retard!” on the train) and tripped up - among the more worrying phenomena. While we aren’t talking a majority of people by any means, the sheer regularity of it suggested a rather raw and jagged edge to society which I haven’t quite fathomed.

[Editor’s Note:

My God can human beings be disappointing.]

In a number of countries I have been travelling with a sighted person (friend, relative) and had people studiously address them rather than me as if I were conveniently absent: “What does he do all day, poor thing?" "Are you his carer?” etc. While the people with me have inevitably been mortified, there is a certain default perception amongst a lot of people that a person with an obvious disability is several sandwiches short of a picnic.

Three very random and specific questions about your experience: 1) When you're talking to people, do you have a picture in your head of what they look like?

2) We judge so much about people based on visual cues; what sorts of cues do you rely on?

3) Do you find being blind is any way a gift, or that there are blessings in being blind?

My “picture” of people is a complex hybrid - there is a certain visual element but there is a lot of audio stuff in there as well. My lack of visual cues has been a real stumbling block in conversation - I have had to work particularly hard on gathering similar information from tone of voice, hesitations and pauses and other auditory cues instead.

“Gift” is a hard question, as is the topic of your post when applied to disability, “the value of broken things”. I feel increasingly that part of the human condition is limitation. We are not God, nor are we completely self-sufficient. Blindness is one, very obvious, form of limitation but there are others (some less visible, others more so). It’s not necessarily a ledger, either, where one limitation gets compensated with an equal bonus. All of us will be heirs to disability if we live long enough (which is why some in the disability community talk about “TABs” - the “temporarily able bodied”).

That said, everyone has, and is, a gift of some sort. Disability merely reminds us that humanity is a common enterprise, with each of us called to supplement each other’s limits.

Turning to pop culture, How do you think pop culture does with disability in general and vision impairment in particular?

In general, I feel that it is a disappointing “cardboard cutout”. Disability is often a “peg” upon which to hang a character’s persona rather than one integrated part of a complete personality.

Pop culture presents some standard tropes for the blind. There's blind person has heightened senses; blind person is wiser than the rest of us, sees to the heart of things, can't be lied to, even sees the future. Or -- and this might extend to disability in general -- blind person is super nice, sweet, nonthreatening.

There’s those (think Tiny Tim from Christmas Carol). There’s also what the remarkable (and sadly late) Australian disability rights advocate Stella Young used to call “inspiration porn”: the idea that just because someone with a disability can interact at any level with the world around them, they must be a “hero” and “so brave”. It’s not that many people aren’t brave for doing just that, but again, this does not treat people as individuals. For some folk with a disability, just getting out of bed is a genuine challenge; for others, post-doctoral research or Olympic athletics may be all in a day’s work. “We are all individuals” (to quote a classic Life of Brian line). I think this is something of the flip side of the approach I mentioned above - the assumption that someone with a disability is incapable until proven otherwise.

There are also slightly darker tropes, too. The worst of these is probably disability as a reflection of moral depravity. I just saw Wonder Woman and, while there is much to say about the movie (not bad, overall, I thought), I was disappointed to see that Isabel Maru, the dastardly German chemist, just had to have a prosthetic on her jaw and an obvious speech impediment.

There’s also the angry disabled person who just won’t accept the way they are (in some cases people are justifiably angry - but this has more to do with the way society treats them). On that topic, have you seen the trailer for Jeremy the Dud...it looks as though it could be quite fun if they get it right!).

[Editor’s Note: Highly recommend that trailer. A brilliant, funny take on disability.]

What do you wish would be part of the portrayal of blindness or disability in pop culture that currently isn't? What are the things about being blind that you wish pop culture better understood?

It would be nice if people could be people first rather than plot devices. There is no “one” experience of blindness: it affects all of us in different ways. Some are born without even light perception, others go blind gradually, others have a mixture of other symptoms which go with it. The same is true of other disabilities.

These things all bring their own experiences with them - some good, some bad. There can be a camaraderie in overcoming shared obstacles (like crossing streets or fighting for more accessible facilities or shared experience of discrimination). There can also be a reaction against being shoehorned - the angry person with disabilities is not just a stereotype but, as with other people discriminated against on various grounds, we tend to forget that the anger often comes from somewhere perfectly valid. Because, beyond and below all of this, people with disabilities are people.

In your email to me you talked about if you had a quarter for every time someone asked you about Daredevil, the community budget would be well and truly sorted. First of all -- and this is just me fascinated by people -- is it usually in the form of a joke, aka "Were you out last night fighting crime? Do the Jesuits offer ninja training? Is Foggy Nelson really that annoying in person?"

Or is it more just, "Have you seen Daredevil?"

And do you find people mention Daredevil because they're a little nervous about the fact that you're blind and they don't know what to do with that? They're trying to make a connection and that's all they've got?

How does the Matt Murdock/Daredevil story strike you? Do you find it reinforces stereotypes of vision impairment and disability? Or challenges some? Both? Neither?

[This is the ugliest run-on set of questions ever. To both readers and Justin, I apologize.]

This is sort of an answer to all of the above. The blind person with super perception, second sight or prophetic abilities is a myth. I think because producers or others are so unfamiliar with disability, it becomes something exotic with a bunch of stereotypes attached - a bit like the ethnic, racial or gender stereotypes of previous generations.

And because most people have no insight into the worlds lived by people with disabilities, they reach for the stereotypes as a point of contact - a presumed entry point into a world they do not know. I think they do it in good faith but, of course, it merely reinforces the point that they are interacting with a person of their own construction, rather than a real person.

Listening would seem to be a great cure for that. By entering the worlds of people with disabilities and realising their essential “peopleness” first, we can cease seeing disability as the strange, exotic other to be constructed anew.

Have you seen or read Daredevil yourself? Or found other blind characters in pop culture that you thought worked?

I confess that I haven’t seen Daredevil. I have seen the plot summary and trailers but am not really familiar with the character.

I don’t think I have really come across a blind character in pop culture who really works. The closest might be the landlady in Deadpool who at least provides something of a comforting and supportive presence and is imagined as a bit of a persona beyond her lack of sight. If her character were developed …. (I haven’t read the comic, so don’t know if we hear any more about her.)

[Editor’s Note: We do.]

What are some pop culture characters or stories that speak to you? And what is it about them that you relate to?

I think the stories I like best are the ones which bring out the commonality with the “outsider” and reveal that the outsider in fact belongs “inside”. Ironically, though it was heavily panned, I rather liked some of the thinking in Suicide Squad: the amoral “freaks”, presented as the worst of the worst, who are gradually shown, as the film develops, to be considerably more ethical than their grey “handlers”.

For similar reasons, I found Blade Runner’s gradual upending of the inhumanity of the Replicants spoke strongly to me of the kind of marginalisation faced by people with a disability whose experiences are often reduced to their disability without regard for their rich and diverse worlds. I was particularly moved by Roy Batty’s speech towards the end of the film:

I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.

[Here’s the clip itself, with the scene beforehand for a little context.]

In your email you also made the comment that "When the superhero movies are at their best, they defy genres and get people to look again at what constitutes weakness and strength." I love that quote. For you what are some examples of that?

One great example would be the Hulk, whose very weakness and damaged humanity is his “power” - something both used and abused by those who would harness his abilities to their own ends.

Or again, the misfits in Suicide Squad whose “powers” are coupled with hurt, damage and flaws. This is not to say that I think disability is a flaw or a break - I think that it is a natural part of being human. I do think, though, that we need to look again at limitation and strength since they are often two sides of the same coin.

Last question: It strikes me as I've formulated these questions I've made them pretty much exclusively about being blind. Would you say that itself is an assumption or stereotype that needs to be challenged -- i.e. that what blind people need or most relate to is more stories about being blind?

Put another way: What would you like pop culture to look like twenty years from now?

I would like to see a world in which we are comfortable in our own skins - however they are constructed. Just as we are now starting to have black or women heroes and villains with their own lives and personality in a way we didn’t several years ago (a project which is still unfinished), I would like to see the same diversity in our coverage of disability. Heroes and villains where disability may be part of the backstory or makeup and even an integral part of their experience but where it does not determine the character to the exclusion of everything else - think, for example, of Peter Dinklage’s character Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones.

That, of course, means listening to folk with disability and a genuine reflection of their diverse experiences.

Today as I was putting this together, Justin dropped me a note with this link to a recent Guardian article about disability groups protesting the casting of Alec Baldwin as a blind man.

A quote from the article: “Alec Baldwin in Blind is just the latest example of treating disability as a costume,” said Jay Ruderman, the foundation’s president. “We no longer find it acceptable for white actors to portray black characters. Disability as a costume needs to also become universally unacceptable.”

Justin had this to say:

This article, in which a prominent disability rights group condemns the use of disability “as a costume”, provides an interesting counterpoint to my comment on disability being used as a peg on which to hang characters.

It also kind of links in with my point that our treatment of people with disability lags behind the way we treat other people who have historically been excluded from the dominant discourse in society. Quite rightly, we no longer regard it acceptable to have men acting as women (as we did in Shakespeare’s day) or people in blackface (as we did 70 years ago). The social acceptance of people with disabilities, even in first world countries where discrimination is being noticed and called out more and more, is still not complete.

Other, nastier, more “real world" indicators of this away from the entertainment industry are the way we deal with abortions (it is noteworthy that countries like the UK or Iceland make it easier to abort foetuses with disabilities than others) or the relative lack of condemnation for murders of people with disability (the term “mercy killing” is often used - without any reference to whether the victim might have viewed it that way).

Again, thanks very much Justin.

++ LINKS ++

This clip of a Chicago weatherman getting emotional as he talked about the eclipse is very sweet.

Also for the occasion the New Yorker did this short piece on Bonnie Tyler’s 1983 hit “Total Eclipse of the Heart”, and it’s pretty great. (It also comes with a link to the music video, which you should watch, because it is insane.)

This Washington Post piece about the lifelong friendship between former Cabinet secretary and California internment camp survivor Norman Mineta and retired Senator Alan K. Simpson is also pretty wonderful. (If you need to clean out your tear ducts watch the video.)

And if you didn’t see University of Virginia graduate Tina Fey’s strong and funny response to the events in Charlottesville here it is.

A thousand years ago a total eclipse might have resulted in social upheaval, human sacrifice, even revolution. This week we tweeted about it and moved on. Progress comes in many forms.

Whatever the week holds, don't worry. You got this. And you're not alone.