EPISODE 125: CHARLIE BROWN'S LITTLE LOVE

POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

Earlier this month I wrote a piece for America Magazine about the origins and unexpected success of “A Charlie Brown Christmas”. As much as we think of the special today as one of the essential Christmas TV programs (over fifty years after its creation it does remain one of the popular television programs aired during the holiday season), at the time of its creation it was a huge risk, with a muted, meditative pacing unheard of for a children’s cartoon, and a deeply melancholic take on society – if you haven’t seen it in a while, you might be surprised at just how much time the piece devotes to condemning society for losing track of the meaning of Christmas. Both its creators and CBS, the network airing it, expected it to be a huge failure. It likely wouldn’t have even gotten an airing if CBS hadn’t already advertised it in TV Guide.

Pieces like that, where you take something that we all think we know so well and turn it upside down to uncover all kinds of other cool stuff, are always fun to write. Even knowing intellectually that the world is a lot more interesting than we often realize, everything is still so much more interesting than that. (Also, I think it’s possible that the richest and most varied emotional experience in human life is surprise.)

But as is often the case when you write a piece like this, you end up leaving so much good material on the table than you’re able to print. Like, for instance, Charles Schulz was so protective of his characters that he went through the cartoon cell by cell, challenging any image that he felt betrayed the look or “rules” of the Peanuts universe.

(A funny case in point: in the comic strip, Charlie Brown’s head always faces in the same direction as his body. Yes, that’s right, believe it or not, Charlie Brown never, never is shown turning his head.

Obviously, this is a huge problem when you’re dealing with moving images. But Schulz did not want that rule violated. Finally, a compromise was reached in which Charlie Brown could in fact turn his head, but his body quickly follows.)

In fact I actually found a whole other story about “A Charlie Brown Christmas” that I wanted to tell, a behind the scenes secret origin-type story that seemed particularly relevant and challenging for our country today. I desperately wanted to slip it in somehow, but I just couldn’t quite make it work.

But I can’t quite let go of it either. So let me share it with you.

When we think of Charlie Brown we think of Charles Schulz, and the wry, melancholic Midwestern Protestant sensibility that informed his work. Schulz was from St. Paul, Minnesota, raised Lutheran. As an adult he volunteered for a time as a Methodist Sunday school teacher. And while “Peanuts” may have universal appeal, it was always also clearly the work of a Christian. In fact, according to a wonderful piece on the spirituality of Peanuts published earlier this year in the Atlantic, more than 560 of his strips included some sort of religious reference. (In contrast, they count only sixty one strips where Lucy pulls away the football.)

“I preach in these cartoons,” Schulz once said about his work, “and I reserve the same rights to say what I want to say as the minister at the pulpit.” After his death Schulz’ wife Jean talked about how offended was by readers who criticized him for being religious. “I think he probably felt that the bible verses aren’t just for church,” she told WHO. “They’re not for the priesthood; they’re for everyone.”

(In the later years of his life he also showed no hesitation to criticize what he called “those shallow religious comics” like Dennis the Menace, praying “about some cutesy thing that he’d done during the day”, or Family Circus’ many references to Jesus. Said Schulz, “I can’t stand that. You could get diabetes reading them, couldn’t you?”

(I have to say, I love the idea of Charles Schultz reading this and getting so angry

he sets the newspaper on fire.)

But “A Charlie Brown Christmas” and the dozens of cartoons that have followed are actually not just a product of a Midwestern Christian, but a Jewish man from San Francisco and a Mexican-American Catholic who it seems very likely came to the United States as the child of a undocumented worker.

Lee Mendelson, who produced “A Charlie Brown Christmas”, was a documentary film maker who had already done a celebrated piece on Willie Mays for NBC when ”the idea of following my first special about the world’s ‘greatest’ [baseball player] with a program about the world’s ‘worst’ just popped into my mind.” And so he reached out to Schulz and with his blessing created “A Boy Named Charlie Brown.”

Ironically, no network was initially interested in the documentary. But in the meantime he and Schulz were approached by the McCann Erickson advertising agency about whether Schulz, whose “Peanuts” had recently been on the cover of Time Magazine, might be willing to produce something for the holidays for Coca-Cola.

The role of producer is often imagined as the “money guy” who brings together the funds and talent to make a project work. But in the case of a “A Charlie Brown Christmas” Mendelson was much more than that. He and Schulz brainstormed about the story together, and in fact it was Mendelson mentioning he had recently read Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Fir Tree” that led to Schulz coming up with the cartoon’s central idea of the broken-down little Christmas tree, what he called a “Charlie Brown-like tree.”

Mendelson also brought in jazz composer Vince Guaraldi, whose iconic work on “A Charlie Brown Christmas” gave the cartoon its uniquely meditative, melancholy tone. And when they couldn’t find satisfying lyrics for Guaraldi’s lovely instrumental piece “Christmas Time is Here”, Mendelson even ended up writing the lyrics himself.

It might surprise some to realize that one of the great songs of the Christmas season was actually written by a Jewish man. In fact, as the Tablet pointed out in 2009, many of the most iconic Christmas songs have been written by Jewish songwriters, including “Silver Bells”, “Winter Wonderland”, “I’ll be Home for Christmas”, “Let It Snow”, “The Christmas Song” and “White Christmas”.

(This popular Christmas song that you have definitely heard fifteen times just today had no Jewish composers. But, according to the interwebs, "Jewish musician and songwriter Kenny G was the best man at co-composer Walter Afanasieff's wedding."

So...there's that...?

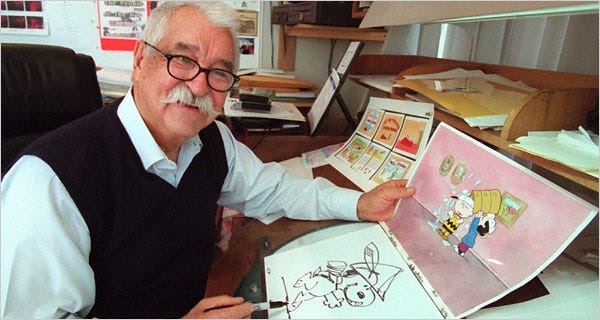

Head animator Bill Melendez was born in Hermosillo, the capitol of the state of Sonora about 180 miles south of the Nogales, Arizona. His father was a military man who wanted his son named Cuauhtémoc, after the last Aztec emperor. His parish priest refused, saying “That’s a heathen name”. And so he was christened instead José Cuauhtémoc.

(I know, what about “Bill”, right? Turns out, that came much later. Melendez’s first work as an animator was with Walt Disney, working on major films like “Fantasia”, “Bambi”, “Dumbo” and “Pinocchio”. And other animators complained that his name was so long “it’s going to hog all the credits.” So they just decided to call him Bill instead. (True story.) And he agreed, in large part because he loathed the name José. “I hate that given name. It’s a terrible name. I hate my father for submitting to that,” he told a group of students at USC.)

(It's a long interview, that one, but there's great gold about both his family and Schulz starting around the 45 minute mark.)

While Melendez was an American citizen by the time he was hired by Schulz, when he came to the U.S. as a child in the 1920s, his mother insisting it would be good for him and his siblings to learn English, it seems unlikely that she went through any kind of immigration process. I spoke to someone at his studio this week who had worked many years with Melendez; his understanding from Melendez was that his mother came without documents and settled just across the border in Douglas, Arizona. And it was only when he got drafted that the he became a citizen, the Army summarily granting him citizenship so that he could fight for them in the war.

(I’ve been trying to get Melendez’s son to confirm these recollections. So far I haven’t heard back, so it could be that she did in fact get papers first. But I suspect that whole way of thinking about immigration in the 1920s is entirely anachronistic.)

Melendez had originally thought he might become an engineer, but after school he needed to find a job. Though he had no experience in animation, he applied and got hired by Walt Disney. That might sound surprising, but you know, Hollywood loves people it can form. Melendez and many of his coworkers took classes through Disney five nights a week; that “school” eventually became the great animation school, the California School of the Arts.

Over the decades that followed Melendez moved to Warner Brothers and then United Productions of America, where he produced thousands of successful advertisement campaigns.

It was in that capacity that he met Schulz; Ford Motors was in talks to use “Peanuts” in an advertisement for a new car, the Ford Falcon. And he was invited to audition – far from the normal process for someone of his level of experience and success, but Schulz insisted. “The creator of Peanuts doesn’t want to let New Yorkers or Hollywood types get their hands into his thing and change it,” they explained to Melendez. Schulz was impressed with his background at Disney, and the flatness to the art UPA created was similar to Schulz’ own aesthetic.

And with that, Melendez became the one and only animator Schulz trusted with his work. But just like Mendelson, Melendez’s impact extended into even more surprising realms. Schultz insisted that Snoopy could not talk. And yet, they knew they needed to come up with some sort of “voice” for him. So Melendez started playing around with audio of himself laughing, sobbing or howling. Eventually they settled on a version where the sounds were artificially sped up. (Here's a great little video in which Snoopy's voice is slowed down to the point where you can hear the original voice.)

The idea was to hire a professional voice person to do this Snoopy; but the time they had to produce “A Charlie Brown Christmas” was so incredibly tight they just ended up keeping Melendez’ version.

And from that point on, Melendez became the voice of Snoopy. Later, he would voice Woodstock the same way.

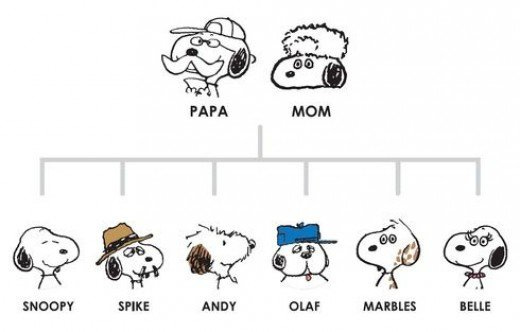

(Decades later, when Schulz drew Snoopy’s father Baxter for the first and only time, he actually resembled Melendez a bit, with the same thick bushy mustache.)

If most of these characters are unfamiliar to you, you are not alone.

I had to double check to make sure they were all legit. Belle? Marbles? Really?

So here’s the point, at least as I see it: right now we seem to be entering into a period in which there is great skepticism about the American project, and more generally about the wisdom or even value of entrusting ourselves and our countries to people who are different from us, who are not from “here” (however we might imagine that).

And at the very same time, this year like every other people from all over will curl up with our families and our hot chocolates and savor the quiet beauty of “A Charlie Brown Christmas”. And its production embodies the very belief that many of us are calling into question, namely that our different groups, whether distinct because of geography, religion, ethnicity or even legal status, have the capacity to work together and create something special and lasting.

I don’t mean to take a Christmas classic and turn into some kind of instrument for polemic. (If you want to drive yourself crazy, google “Charlie Brown political” and see what comes up.)

On the other hand, for me the greatest moment of “A Charlie Brown Christmas” is the ending, when all those mean kids who have been mocking Charlie Brown see the little tree that he cared for siting there dead and abandoned, and are so moved that their cynical and defensive posturing drops away and they work together to fix it up, then suddenly break into song.

“It’s not bad at all, really,” Linus says, wrapping his blanket around its base. “Maybe it just needs a little love.”

Wiser words...

++

I will not write about Rogue One yet....

I will not write about Rogue One yet....

I will not write about Rogue One yet...

....but I want to.

You’ve got until after New Year’s. After that it’s all fair game, people.

++ LINKS ++

A panda destroying a snowman.

Darth Vader gives his grandson the best Christmas gift of all.

C-3P0 has words for K-250. (Note: Some colorful language -- but now I want C-3P0 to always talk this way.)

And a New York kid turns his own struggles into a motivation to become a modern day Lucy.

++

A blessed and happy (and hey Baby Jesus how about also working your divine Christ Child light of life magic and making it maybe occasionally restful, too?) Christmas to you all.

“May your days be merry and bright....”