Episode 117: A Good Death

POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

Let me ask you something. When you were a kid, dreaming of the future in all its rich and wondrous possibilities, did you ever imagine a day would come when you could join seventeen million people in watching two men get beaten to death by a bearded dude with a barbed-wire-wrapped baseball bat on national television?

Ah, 21st century America. We’re so divided on political issues some fear a revolution; yet offer up the brutal death of a fictional character and we tuck in as close together as the Cleavers watching Cronkite on the evening news.

There’s been a lot written in recent years about the way death has become a too ready go-to move on television. And considering a show like “The Good Wife”, which hadn’t exactly “primed the pump for horror” before it suddenly killed its male lead halfway through the fifth season, I can appreciate that reaction.

It was hard, y'all.

But most shows getting attacked today promised a healthy mortality rate pretty much from the start. I’m sorry, you were expecting a zombie apocalypse that’s “not too bad”? Huh?

I think the better question is not whether there’s too much death on television, but whether there’s enough good death. (As I finished typing that sentence I heard it. Let me just be clear, I am Irish. It’s all about good death.)

For me, death on television works when it accomplishes three goals: 1) it speaks in a meaningful way to the overall journey of a character; 2) it expresses something interesting about the world of the show; 3) it offers some insight into our humanity.

Hitting all three is like when the arrow goes through the arrow that went through the arrow that hit the bullseye. It’s not easy.

But it has been done.

Here’s a couple of my favorite TV deaths.

Oh, and in the words of one of my favorite sort-of-dead-sometimes-maybe characters:

++

Mr. Hooper, Sesame Street (1983)

Remember that year when “Sesame Street” got super dark and everyone was getting murdered by the cast of “Zoom”? It was crazy, right?

Will Lee had played Sesame Street store owner Mr. Hooper for twelve years when he suddenly died of a heart attack on December 7th, 1982. He was one of the first human characters the show introduced, and he was enormously popular both with children and their stand-in Big Bird (who usually called him "Mr. Looper").

The show could have tried to write Mr. Hooper off in some oblique way – Mr. Hooper won the lottery and doesn’t care about any of you any more! Mr. Hooper ran off with the letter “S”! Mr. Hooper went to jail! (believe it or not, those were all ideas they seriously considered) (okay, maybe don’t).

But instead the writers decided to use his death as a teachable moment, offering a whole episode about his passing.

In 1983 I was a little too old to be paying attention to Mr. Hooper any more. I was a lot more concerned about the possible long term health risks of being frozen in carbonite. But going back to this clip where the cast try to help Big Bird understand what’s happened to Mr. Hooper kind of left me in a puddle.

“Sesame Street” isn’t a show with a lot of “character arcs”, beyond when in God’s name is Big Bird going to stop talking to that creepy invisible elephant (its eyes, the horror). But in terms of offering a death that speaks to our human condition, you can’t do much better.

Edith Bunker, Archie Bunker’s Place (1980)

The death of Edith Bunker, at the top of the second season of the semi-spinoff-of-I-don’t-really-understand-why-this-isn’t-still-called-All-in-the-Family, is basically the adult version of the Mr. Hooper storyline. Once again, the death happens off screen (not for nothing, if I were writing “Sesame Street” Mr. Hooper would have died in front of Big Bird – let’s see what sociopath-in-training Mr. Snuffleupagus has to say about that), and the episode focuses on how other characters deal with it.

Whereas “Sesame Street” is primarily focused on helping kids to process this information, “Archie” is all about presenting that experience in a way that is true and recognizable to our experience – the emotion in discovering a random piece of clothing left behind; the sense of never having gotten to say certain things; the long silences.

It’s a great moment.

Joyce Summers, Buffy the Vampire Slayer (2001)

In its fifth season, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” took what Sesame Street and Archie’s Place had done and gave it one slight adjustment. In depicting the unexpected death of main character Buffy Summers’ mom, rather than play the situation straight creator Joss Whedon decided to shoot the episode in ways that would capture the awfulness and surreality of that experience. So when Buffy comes downstairs to discover her mother lying on the couch, her eyes are wide open, and she lays there doll-like and stiff.

So horrifying.

The whole episode plays without a single moment of background music. Almost every scene happens indoors, creating a sense of claustrophobia and isolation.

And people react in unexpected ways – Buffy suddenly vomits at one point, and later blows up when people refer to her mother as “the body”; her friend Willow freaks out about what to wear to the funeral. Even the show’s camera operator doesn’t seem to know what to do; shots are sometimes off kilter, or with large empty spaces in the frame.

There’s no clips I can show you, but if you have Netflix, it’s episode 516, “The Body”. It takes the pain and dislocation of loss and elevates it to something profound.

Ned Stark, Game of Thrones (2011)

When, in the ninth episode of the first season of “Game of Thrones”, main character Ned Stark was brought out supposedly to be executed, and then actually did have his head cut off in front of us, I was so sure I had missed something I actually rewound the sequence and watched it again.

And even after that, I assumed there was some trick or magic whoozat yet to come in the season finale. But nothing happened. As the season ended, he was still dead.

Look at the birds, Ned. Just look at the birds.

“Game of Thrones” has since had a whole lot of big deaths. Oh boy has it. But I’m not sure any of them past, present or future, even the iconic “Red Wedding” (if you haven’t seen the show, suffice it to say, weddings don’t mix with Westeros) – will ever have the significance of the death of Ned. Because in that one bold choice, to kill the main character, who is also clearly the hero, the “good guy” -- the show set forth its world in no uncertain terms. “Game of Thrones” might look like “Lord of the Rings”, but Westeros is not a world in which being good or right means you win in the end. In fact, it probably means you don’t, and don’t deserve to.

And I think audiences loved it not only for that, but because it begged the question, should we really believe that goodness and rightness are somehow by default going to always win out in our world, either? Is that really the story of humanity? Because it kind of sounds like a fairy tale...

Princess Shireen Baratheon, Game of Thrones (2015)

Just looking at this photo I am already upset all over again.

For four years, we watch the would-be-king Stannis Baratheon fight to claim the Iron Throne, which by right should be his. But he doesn’t have a lot of allies; in fact his much more charismatic younger brother has already gotten most of the support, and the family on the throne is clever, rich and powerful.

So to get ahead Stannis keeps selling off pieces of himself to the awful, some-day-soon-gonna-get-her-due Red Witch Melisandre. When first we meet him he’s burning people alive to her god, the Lord of Light; later he inseminates her to create a crazy shadow baby murder weapon that is way creepy; and then finally, having still not yet learned his lesson, he agrees to let Melisandre take his sweet daughter Shireen and SACRIFICE HER ON A PYRE, WHICH IS NOT OKAY, IT’S NOT OKAY, I AM NOT OKAY WITH THIS.

The violent death of a little girl...it’s probably the worst thing that has ever happened on “Game of Thrones” (and honey, that’s saying something). It is a terribly apt ending for Stannis’ awful story. And in the midst of our modern show-every-drop-of-blood TV landscape, the sequence is notable for its decision to focus instead on people’s reactions as the unseen Shireen pleads and then screams and oh God is it awful why is the world like this.

And yet it is.

Poussey Washington, Orange is the New Black (2016)

Like a lot of deaths on this list, the accidental homicide of fan-favorite Poussey on last year’s season of “Orange is the New Black” is effective in part because it comes completely out of the blue. Nothing in the writing telegraphed in any way that Poussey was going to get killed – she has no big valedictory speech or heroic moment that seems to wrap up her story. She dies in fact without anyone even knowing it’s happening.

Her death is also a big deal for being an attempt to try and talk about police brutality in a thoughtful, nuanced way. The guard responsible for Poussey’s death didn’t intend to hurt her; in fact, he was so focused on the chaos around them he didn’t even know she was in distress. As is so often the case on “Orange”, the real tragedy comes not from the individuals alone but bigger social structures that are doing undue harm on everyone. It’s an insight one wishes our media and government could bring to the conversation.

The real reason I include Poussey’s death, though, is because of the episode that follows, in which in flashbacks we follow Poussey through one great night of her life. Although it’s definitely a moment in her past, it also plays like what her afterlife might be like, a world of new friends and dancing and monks on bicycles, and above all joyous freedom.

Here’s her final moment. I really love this episode so much.

Lt. Col. Henry Blake, M*A*S*H* (1975)

When M*A*S*H* killed off camp leader Lt. Colonel Henry Blake in its third season finale, it broke the internet before Al Gore had even invented it.

Really. It's true--I was six years old, and yet I remember it. It was a HUGE deal. At the time, killing characters was not a thing that TV shows did. Sure, an actor might leave midway through a series, but you never wanted to write an ending that meant you couldn’t get them back.

But when actor McLean Stevenson asked out of his contract two years early, M*A*S*H*, with its comic and yet bleak, weary-eyed look at the reality of war, saw it as a chance to do something great.

And also brutal. For those who don’t know the episode -- what, you don't know 70s TV?? Three Hail Marys. -- it begins with Blake getting a telegram from his assistant Radar that his discharge papers have come through. He’s leaving, stat. The episode is filled with goodbyes and reminiscences, and then he flies away.

Then, in the next scene, while all the doctors are working, this happens.

Some people thought the choice to kill off Stevenson was a form of punishment for breaking his contract. This way, he could never come back. But creator Larry Gelbart later insisted that wasn’t the case. “Having Henry die was not a show-business decision; we were not punishing an actor for leaving the series. We were trying to make his departure one that would be apt, as well as memorable.”

(Gelbart has more to say here, including the fact that the crew had no idea of the twist until they were filming it; the actors, including Stevenson, only learned of it shortly before filming it.)

It’s definitely one of the most shocking and powerful deaths ever on television. And yet again, unlike most deaths today, it worked as well as it did in part because they didn’t show it.

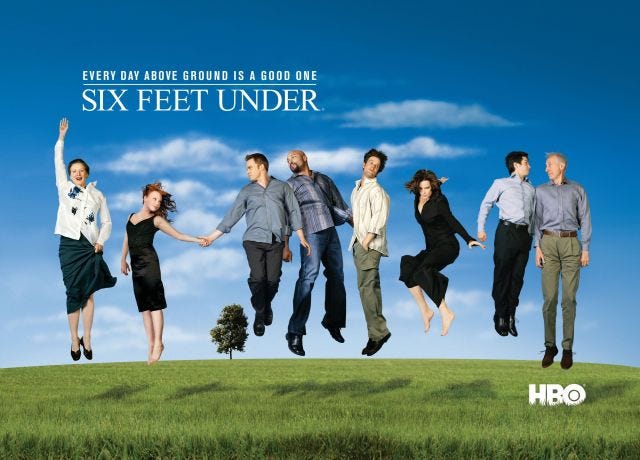

Cast, Six Feet Under (2005)

“Six Feet Under”, about a family-run mortuary, was a tremendous show about life and death that eventually veered into I-don’t-know-what-is-going-on-but-everyone-is-angry-and-damaging-themselves-and-I-am-uncomfortable, but-at-least-there's-still-that-unbelievably-great-title-sequence-to-look-forward-to for a while.

But then, in the final sequence of its series finale, it not only returned to its early greatness but delivered maybe the most moving and astonishing TV show ending there has ever been. Mostly, I think, because it reclaimed the key insight of the show, that death is coming for all of us, and not necessarily in the way we might expect (or like), but that seeing it all as it is only reveals more clearly how hilarious and painful and gorgeous this human existence is.

Say what you will about people dying in unexpected and surprising ways. It can’t top this.

++

There are so many other great TV deaths I would love to talk about. The series finale of "Lost", when you find out everyone has died (except for Hurley) -- I know some people hated that ending (ENOUGH ABOUT THE OUTRIGGERS, PEOPLE!); it left me sobbing so hard I had to shut windows.

Charlie drowning. Omar Little getting clipped on "The Wire". Walter White letting Jane die. The death of the Eleventh Doctor, Matt Smith (he was my guy). The Red Wedding. Carol and the flowers.

Actually, there's one more great TV death I want to share with you. It's from 2002; it made Hawaiian musician Israel Kamakawiwo'ole a household name (and one of his songs a staple at funerals). It perfectly captured the character, the way audiences felt for the show, and I think the dream most people have for their own deaths.

Check it out. A truly happy death. Bring tissues.

(Okay, yeah, towards the end there may be a crazy moment where people start talking and they sound like Italian cartoon characters. What can I say, it was the best I could find. Consider it value added.)

++ LINKS ++

This article from Douglas Rushkoff about why we should stop buying new phones every couple years, the people that are getting hurt because we want the newest thing, will really get you thinking.

This week Donald Glover was cast as Young Lando Calrissian in the coming Young Han Solo movie. (His mother apparently told him, no joke, "Don't screw it up.")

Last summer Conan O'Brien released the tryout tape for Young Han. Definitely worth a gander.

And lastly--did you know that being in space radically changes astronauts' point of view on life and humanity? It's true, and it's pretty cool.

Have a great Halloween. Don't be afraid to leave it all on the field. One person cutting loose gives everyone permission to have a good time.

Or so I like to tell myself.