POP CULTURE SPIRIT WOW

The Ivy League has been in the news a lot in the last year, and in a very particular and dire way in the last week, as the current administration has begun refusing to hand over hundreds of millions of dollars promised to the institutions.

Randomly, I’ve been on a little journey of my own with the Ivy League this last couple months. It’s a story about the people who truly see you, and how your sense of an experience can change so dramatically, and maybe in some small way about the importance of universities.

Halfway through my junior year of college, my English advisor Dr. Tim Machan broke some news to me that I didn’t know how to deal with. You can’t apply to get your PhD in English at Marquette, he told me. You need to look at the Ivy League.

This hardly seems like a difficult thing to be told, I know. But I adored Dr. Machan. I’d had him for my very first English class, then studied Chaucer with him and Literature of the Vikings, which is basically the metal version of medieval lit. I would go on to spend a full year going each week to his office, which had that chestnut-y smell of pipe smoke like something out of Tolkien, learning Old Norse with him. Why would I possibly want to go and work with anywhere else?

Tim Machan in more recent times, a professor of English at Notre Dame.

Also, as much as I did well in school, I was hardly a prodigy. The Ivy League? Go on. But he persisted until I agreed to humor him. That fall I applied to Harvard, Cornell, and Indiana.

When the response letter came from Harvard, I was so entirely freaked out that I asked my hall director to open it and read it first. Preposterously, I had gotten in both there and Cornell. And over spring break three friends and I drove from Milwaukee to the East Coast, where I visited both schools.

Hours before I left with my friends, on a cold March day, I got a phone call from the executive assistant to Marquette’s president, a Jesuit named Albert DiUlio whom had started in the fall. He was good friends with Fr. Bill Leahy, the Jesuit who lived and worked in my dorm—he of the Deism, hmm that I mentioned last week—and over the course of the year I had consequently run into him a number of times. The first time I was wearing a T-shirt that said ‘Marquette University: 9 month party, $10000 cover charge". When I was told who he was I was horrified, to his abundant delight.

Fr. Albert “Al” DiUlio today; here’s a nice recent profile of him.

“Fr. DiUlio would like to see you now at the Jesuit Residence,” his assistant JoAnn told me. I had never been to a Jesuit Residence, nor received a call from a Jesuit’s office, and both sounded bad. But based on JoAnn’s tone neither seemed like a thing I could successfully avoid, either.

Feet dragging every step, I walked over to the Jesuit community, an unassuming block of a building on Wisconsin Avenue where the Jesuits were rumored to have beer on tap (which was true). A receptionist called up to Father DiUlio’s room and then took me up. And there he was, in a very nicely appointed apartment, wearing a colorful sweater over a clerical shirt with the tab removed. “Sit down, James,” he told me.

He asked me if I was ready for my visits. Sure, I said. “Here’s the thing,” he told me. “I’m afraid you’re not going to give Harvard a chance. And that would be a big mistake.”

He went on: The Ivy League would be hard, but that would be a good thing. “You’ve had it easy at Marquette,” he told me. “It’s time to challenge yourself.”

I sat there, my jaw sort of swinging in the wind. The fact was, I had been talking down Harvard, for absolutely no good reason but fear. But I didn’t realize I’d been doing it. Also I didn’t know whether to be flattered or offended that he thought I’d had it easy at Marquette. I worked my ass off.

I agreed to try and be open, though I was in fact dumbfounded, really, to have been so totally seen. Moreso than I’d seen myself.

My friends and I drove to Cornell first. Honestly all I remember was thinking it was incredibly isolated. The tour guide talked about how it snows for six months.

Then we drove to Harvard. As soon as I stepped on the campus, I was swept off my feet. If you’ve been there, you probably know the feeling. It’s a special place.

I had a lunch session where I got to meet other possible members of my class. Maybe I also met Derek Pearsall, who was the main medievalist at Harvard at the time. But at that point it was all gravy, like when you get to spin the wheel after you’ve already won money on The Price is Right. I was definitely going to Harvard.

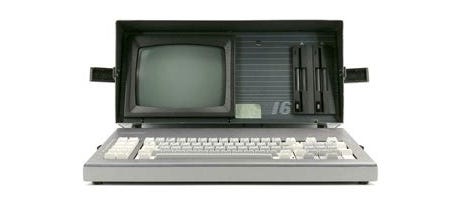

And so with Dr. Machan’s encouragement and Fr. DiUlio’s approval (and Fr. Leahy’s Kaypro, on which he had written his dissertation), I traveled to Boston that September to begin my PhD.

Bow before the mighty Kaypro.

Harvard was a disaster almost immediately. After spending three of four years living in a single sex dorm, I opted for the same at Harvard, because I had no idea how to live with women. I ended up one of seven guys in singles on the garden level of a grad residence hall that fronted on the law school student volleyball courts.

If you ever need to resent male law school students, spend a year watching them strut around playing volleyball.

Almost immediately I was introduced to the medievalist crowd. They invited me to watch Monty Python and the Holy Grail. And I thought, Over my dead body.

I admit, this is a strange reaction to an invitation to watch Monty Python. Especially since I’d spend endless Sunday evenings sneak-watching sketches from it while my dad slept, hoping beyond hope that he would stay asleep long enough for me to watch Tom Baker or Peter Davison in an almost certainly incoherent episode of Doctor Who.

But a childhood of ridicule about anything smart or creative-adjacent had properly trained me to believe (stupidly) that things like Python or Doctor Who or comic books or science fiction were never to be publicly acknowledged or embraced. Not if you wanted friends.

So, even though I had now reached a point where all that nerdery was not only welcomed but the source of my success, and I had arrived at Nerd Central and was invited in (and Python was great), I recoiled so hard I never spent any time with that group of students at all, and almost immediately cast aside any interest in medieval lit.

Two months later my 13-year-old sister was killed in a freak car accident. Though I did go back to school, any spark of interest in grad school was gone. I spent my evenings walking the cobblestone streets of Cambridge, reeling, searching, wondering.

The Jesuits of Cambridge, of whom there were many at the time, had a lot to do with how I got through that year, especially the Jesuits of a little community called Zipoli House, who more or less let me become part of their family. I had already been in conversation about entering the Jesuits—weirdly, within my first three days in Cambridge I had met one at the bank, and two literally as my parents and I first arrived in Cambridge. One of those two, Tom Manahan, lived at Zipoli House and for some crazy reason that I could not explain to you even now made me his friend.

Zipoli House, today.

When my dad called to tell me my sister had been in an accident and I needed to come home, it was Tom I called, and Tom who immediately understood this was almost certainly much more serious than I understood.

I applied to the Jesuits, got in, and was set to start that August. But I was damned sure not leaving Harvard without having something to show for it. As it turned out, my first year at Harvard was my program’s last year of expecting students to take 4 graduate classes each semester. As it turns out, an MA required 8 classes plus a language exam. (I used to say “simply” 8 classes, but 4 Harvard grad classes a semester, each requiring a 20+ page paper, was an absolute bear. The department changed its requirements to three classes a semester precisely because so many students were taking incompletes.)

During the weekend after Easter break, Father Leahy’s Kaypro died, destroying one of my papers and leaving me 48 hours to rewrite it. I got a B+, which sounds great, but we had been told that a B+ was the lowest passing mark. Basically, if you get a bunch of B+s, maybe you needed to think about what you’re doing here.

I got three that year.

Meanwhile I failed my first language exam, because I insisted on taking Latin, a language I had only studied on my own, which was a ridiculous choice on my part.

But thanks be to God and Baby J and all the angels and saints, I passed a Spanish language test, which along with the 8 classes meant that I was indeed eligible for the MA. It was sent to me that next fall while I was in seminary.

That was effectively the end of my affiliation with Harvard. Though I would put it on resumes, I made no attempt to stay connected to the university. I didn’t think I had any right to. I’d spend one no good very bad year there in the 90s and had my absolute poorest academic experience. Basically my degree was a scam.

How crazy this got in my head: I went back to Cambridge from 2000-2003 to study theology at a little Jesuit school nearby, the same place Tom and the guys from Zipoli had gone, and spent three glorious years there. I lived literally a three-minute walk from the beautiful yellow house where I had sat and been a part of classes taught by Sacvan Bercovitch (a dazzling American scholar) or the poet Seamus Heaney. (When I entered the Jesuits he sent me a little postcard of Jesus’ disciples casting their net over the side of their boat, and quoted Jesus: “I will make you fishers of men.”)

And in that three years I never once went over there to say hello or see if there was still anyone there I would know, like the department assistant who had been so kind to me when my sister died. In fact, I never even considered it. It felt too embarrassing, like I’d be claiming some status I hadn’t earned.

Ironically, my years at Weston were exactly what Harvard was meant to have been, a time filled with a rich exploration of ancient, often almost mythological texts, just from the Hebrew Scriptures rather than Norse sagas, and the relish of digging into complex systematic thinkers. In a way it begged the question of whether that long ago experience was the shame I had come to believe it was. But I never considered that possibility.

Then, a couple months ago, I was glancing at my bookshelf, and came upon a book that my old professor Tim Machan had given me the year after I was ordained called English in the Middle Ages. I was headed from Milwaukee to work in New York at America Magazine.

Over the course of many moves and the purges that came with them, this book, which I had never read, survived. Even the move into an apartment, which entailed getting rid of maybe half of what I owned, had not bested it. I’m not sure Tim and I have even spoken since he gave me that book. But the debt I feel to him remains. I may have flubbed the opportunity he gave me as dramatically as a soccer player kicking a goal into their own net, but still, Tim saw things in me that I didn’t see myself. He expanded my sense of what was possible for me.

All these years later, I finally opened his book in my little studio in New York. This is what I found on the inside cover.

Is it strange to read something you know was written for you 20 years ago and believe it had something to say to you today?

Since I read that, I’ve been thinking about my time at Harvard. And finally this weekend I took a trip back to Cambridge. In part I came to see some friends, but I also really just wanted to go back to Harvard, in some ways for the first time in 33 years, and see if I could somehow reestablish a connection between me and this world. Face the music, and see whether you could actually dance to it.

I’ve always liked walking around campus. I did that first. It was fine.

I went to the book stores. I’m not sure I’ve ever returned from a trip to Cambridge without an armful of books from the Harvard Book Store, the Coop, and Million Dollar Picnic (which is one of the great comic book stores). I certainly got some more titles to consider, books about the notion of the shore in classical literature, about the five first centuries of the church, in which there were multiple Christianities co-existing, about Gilgamesh. It, too, was fine.

But the real moment of truth was the thing I was still somehow resisting, a return to the yellow house where the English offices were, and the room on the second floor with the long table and the balcony above it where I had my best classes.

As it turns out, the building was now the home of the Folklore and Mythology department. The Friday I stopped by was the beginning of spring break here. The first floor seemed mostly locked doors and a deserted kitchen in the back. Which was a relief, actually. Maybe I could just have a little wander around.

Coming up the winding stair at the front of the building, I arrived on the second floor to find myself transported back to 35 years ago.

I sat there in that empty room where I’d listened to Heaney and Bercovitch and others, drinking in the glorious feeling of being in a space that encouraged and celebrated the work done within it, questions about word choice or translation, about metaphor and metonymy, about Hawthorne and the Puritans and the meaning of America. It was a room for those mining small, precise plots of land on the page, in their mind, with a hunger to discover with them new worlds.

I hoped sitting there might stir more specific memories, too, but either too much time had passed, or I hadn’t been at Harvard long enough or deeply enough to form many beyond that baseline sense of gratitude and wonder. But as it turns out in the sitting that was more than enough.

My dad was a pipefitter. He worked three jobs to put me and my siblings through college, and my mom one of her own. I was able to go to Harvard only because the school gave me a full ride, plus a stipend. When I left to enter the Jesuits they also gave me two years to return without losing my award.

Walking around campus now with the experience of a 55-year-old man, I see so many astonishing opportunities that I would have had at Harvard had I stuck around a little while longer, or known more. But I’m also astonished at the opportunities I did have, and the way that being at the school expanded my sense of myself (even if I didn’t know it at the time).

Universities offer many treasures. But maybe the longest-lasting gift a university provides is the food it offers for the imagination.

This was one of your columns that struck a chord. Funny how it often takes many passing years to realize how formative those earlier years have been. I’ve never visited Harvard but I have similar feelings for the formative years I spent at NYU grad school majoring in Religious Education. Great article.

Beautifully stirring! Transcends the personal to the universal. You had me and I’m better for it.