AUSTRALIA WOW: MY DATE WITH THE HOLY TRINITY (OF CRICKET)

Ignatius did say you can find God in all things...

THE FATHER

Some have compared the sport of cricket to watching paint dry. And after spending two days last week at the Melbourne Cricket Ground watching Australia begin a five-day test match against India, I can say that in some ways that is not an inapt metaphor. For as high scoring as a day of cricket might be—by the end of day two Australia had scored over 450 runs—most of the time those runs are scored in 1s or 2s, and with none of the drama of an American hitter racing round the bases. Pretty much anything that might be considered a single in American baseball generates a run here, and the batsmen—there are two at any one time, at either end of a rectangular strip of soil known as the pitch—usually aren’t having to run too fast to get to the other end to score. If the ball gets past the fielders closed in, it’s kind of understood, that’s a run.

(One of the many wildly incomprehensible elements of cricket for an American: the batsman does not have to run when they’ve hit the ball. So for instance if they smack it right into the waiting hands of one of the fielders around the pitch, it means nothing. Play continues. It’s like the American equivalent of a foul ball.)

So yes, there is a sense in which you can spend the afternoon at the cricket and what is going on happens in such dribs and drabs, it’s like nothing is happening at all.

But after two days watching, I would argue if cricket is like watching paint dry, it’s really like what it would be like to see that happening at a microscopic level, a moment by moment transformation. That is to say, while it’s often slow and quiet, it can also be incredibly intense.

A case in point: the second day of the test match—“Test match”: the traditional five-day version of cricket; India has spent the month of December in Australia competing against Australia in test matches in five cities, with the winner to take the Border-Gavaskar Trophy—began with cricket great Steve Smith and Travis Head at bat.

(Okay, this is going to take a bit to get your head around: Cricket is organized into a series of six pitches from the opposing team’s bowler (aka pitcher) called “overs.” And when a batsman hits a single, he and a teammate at the other end of the pitch switch places, and that other player now bats against the bowler. After the over is, well, over, a second bowler at the other end of the pitch now bowls against the batsmen, and this continues, over after over, until the first ten of the 11-member team has batted and been called out. Then the other team gets its at bat. And then each team gets a second at-bat. Hence the five days.)

Smith and Head had been batting for some time the previous day, and had racked up over 60 runs between them. And as they went on, the sheer fact that they were continuing to score runs became its own sort of quiet drama. How many runs would they be able to score? How high could they take Australia? Would they crack 350? 400?

Along the way there were other dramas as well: Smith had already scored 50 points on his own. Would he make it to 100, or as they call it here, a century? And as it turned out Smith’s at-bat would also move him to number four on the all-time list for points scored.

Each of these moments became its own thrilling little question mark and then mile marker. And watching the game build toward those moments was surprisingly intense. The closest American baseball can come is the duel between a pitcher and a batter (and see below about that), but those are so much shorter in length—I think Smith and Head batted together over the two days a total of something like 2 1/2 hours.

The game stops to give Smith a standing ovation for hitting his 34th century.

When the opposing team is batting, you’re also dealing with a very different version of all this. With each point scored by a twosome, each over where your bowlers are unable to stop their forward progress, there is a growing sense of worry and helplessness. As it went on I found it harder and harder to watch, actually, even though we had a lead of more than 400 points before they even came up to bat. The only thing I’ve ever experienced like it was watching the White Sox in the playoffs in 2005. Each next game, each next round there was only more anxiety about whether the Sox would be able to maintain their momentum. When it was all over, I was I think even more relieved than I was happy.

In the case of the test match, my friend Damien who had invited me to the first two days rung me up about going the last. As it was my last day in Melbourne I really couldn’t go. But later I realized I also just didn’t know that I could bear the tension of watching the Indians bat again without knowing whether Australia could quickly stop them, as had happened in their first inning. (Inning=a whole team’s at bat.)

As it turned out, Australia’s bowlers swept through them that second time through, and managed to win the test by over 100 points. (If the entire Indian team had not been able to bat that last day without scoring enough runs to defeat Australia, the game would have ended in a draw, which after 5 days of play is a very hard thing for my American brain to get my head around.) They’re now 2-1-1 against India, with the fifth test to begin today in Sydney.

THE SON

While a lot of the drama of cricket is quite different from baseball, there is at times a head-to-head bowler versus batsman dynamic that reminds me of baseball. And I actually got to see one such duel that was heralded immediately afterward as historic and representing a permanent change in the game.

Sam Konstas is a 19-year-old kid that had never played test cricket for Australia before. He’d been another kind of cricket called BBL—Big Bash League—where two teams play for an evening and just try to smash as many runs as they can. (Note: If you manage to hit the ball all the way to the boundary of the field of play without the opposing team being able to stop it, you score four points. And if you manage to smack it past that border or out of the park, you get six.)

Konstas got called up for the test, which as I understand it is like a rookie getting to play in the big leagues. And he was slated to be the lead-off batsman, the youngest ever for Australia in the history of test cricket.

His first time up he faced maybe the greatest current bowler in all of cricket, Jasprit Bumrah, who peacocked around from the start with a scowl on his face like he owned the game and was annoyed he had to prove it.

In comparison, Konstas seemed absurdly casual. Early in his at bats, he actually did something that made the crowd laugh—rather than batting in the traditional test way, he tried a trick shot from BBL called a ramp in which the batsman tries to hit the ball at or over the boundary directly behind him. (I don’t think this is exactly accurate, but imagine a baseball batter deciding not to swing at the ball as it hurled at him, but to wait for it to pass and then swing backward, adding to the ball’s momentum and giving it lift out of the park. Yes, this is absurdly difficult.)

(Note: In cricket, there is no part of the park that is considered out of bounds for point-scoring. There are no foul balls.)

Konstas didn’t manage to pull it off, but just the fact that he tried that against the world’s greatest bowler was incredibly gutsy. Bumrah himself walked away laughing, in fact.

A few pitches later, he did it again. And again he missed, but it only built the crowd’s amusement. “It’s like he’s playing cricket in the backyard,” one of the people near me said, with delight.

And Konstas kept doing this trick shot, until it started to work, and suddenly he was scoring 4s and 6s. And Bumrah had no solution for him. The kid had completely rattled him.

Given that Konstas’ at-bat was literally my first experience of test cricket, in the moment I had no idea this was that big a deal. Everyone was amused. And when he finished his at-bat with over 60 points, which is a ton for a first at-bat in test cricket, the crowd roared. But his performance was so totally laid back.

As soon as it was over, though, my friend Damien said to me, “He just changed cricket forever.” And as story after story has poured out about him in the days since, I’ve begun to realize it’s like I got to see Babe Ruth’s first at bat. “You picked the right day to go for your first time!” a friend texted me.

THE HOLY SPIRIT

The two days of test cricket that I got to see happened at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, otherwise known as the MCG or the G. In my years visiting Australia I’ve been to the MCG many times to watch Australian Rules Football. And while I love that game so much, I think a lot of what draws me back time after time is just the chance to be in the MCG. It has, for me, a presence about it when it is filled with 100,000 people, a life force that is unexpected and somehow feels independent of we who are part of what animates it. (I’ve been to the MCG when it’s empty. That presence is still there, but it’s like it’s resting, or waiting watchfully.)

Like so many things in Australia—the immense star-filled skies in rural areas, the ocean, the outback—in the midst of the MCG you feel somehow both small and lucky. It’s like being there puts you in your place, but instead of that being a bad thing, it’s enormously gratifying. Because your place is here, before this living thing of great beauty and grandeur. And being allowed to sit here before it feels like an act of love.

Maybe this section should have been THE FATHER, because for me being in the MCG really is an experience of what I hope it feels like to be in the presence of God. (And hey, it is known as the “G”…) Also Smith was definitely the animating force of the Australian team those first few days.

But then, so was Konstas in a different way. And maybe there’s a way in which that experience of being seen and cared for and reassuringly small is what it was like for people to meet Jesus.

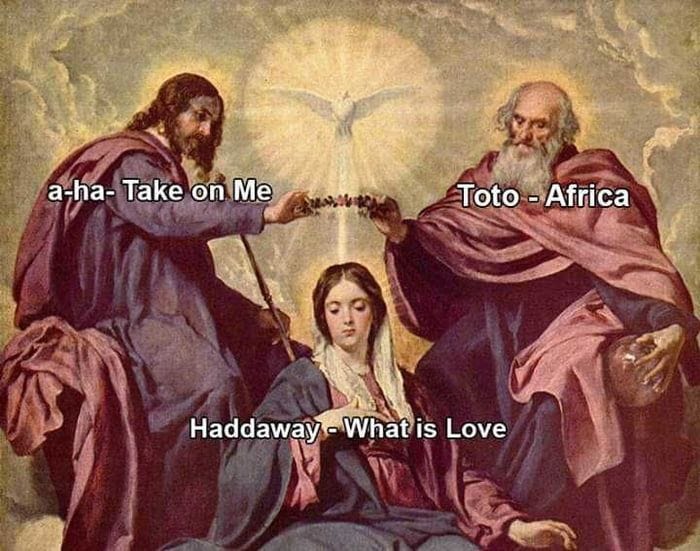

I’ve been to a lot of first Masses on Trinity Sunday. Ordinations of Jesuits in the U.S. generally happen in early June, and Trinity Sunday is right there waiting like an overripe tomato waiting to be plucked.

But those homilies are almost always a disaster. The temptation to try and use your first Mass to finally explain the Trinity is just too great. I’m sure I’d have tried the same if I’d been in that position. It almost certainly would have involved Luke Skywalker. (I am nothing if not consistent.) And it probably would have unintentionally implied that Darth Vader is God, and that is definitely a weird flex for a first Mass, but everyone would have smiled and told me what a good priest I was (while the Jesuits present mumbled “Don’t quit your day job”).

I do think this is pretty genius.

At some point I got comfortable living in the not knowing about all that kind of stuff. I haven’t seen the attempts to explain this stuff bear much fruit. A lot of the time they involve how God loves God’s self, which seems like weird, human language for something that is not human. Don’t get me wrong, I want God to love God’s self, but whatever the Holy Trinity is, I don’t think it’s about that, any more than I think what God really wants more than anything is for people to worship Him. (Why would we ascribe to God a quality we literally hate when we find it present in our own leaders?)

But watching Konstas and Smith and company at the G, I definitely got a glimpse of something. I didn’t totally understand it, but it was very, very good.

(How’d I do, cricket fans? Was I close?)

Back this weekend with an interview with a great lady.

OMG -- am I going to have to read the complete tome about Crick-watchpaintdry-ET?!!?!?

Ha ha ha. Happy New Year!